NAFTA’s rules of origin (ROO) are poised to be a key element in the Trump administration’s pursuit of its NAFTA negotiating objectives, including reducing the US goods trade deficit with the other NAFTA parties. The US is seeking to strengthen rules of origin in order to “incentivize the sourcing of goods and materials from the United States and North America,” as well as streamline associated administrative procedures and ensure their vigorous enforcement. It’s part of Washington’s broader “America First” agenda aimed at creating high-paying US manufacturing jobs.

The rules determine whether goods qualify for NAFTA’s duty-free (preferential) trade, based on where the goods and/or the components of the goods originate. What happens with the ROO piece of the bigger negotiating puzzle could determine whether NAFTA is ultimately modernized to the benefit of all three partners, or imperiled to their detriment. Domestic American politics is expected to push the Trump Administration to seek tighter NAFTA rules, at least for selected products, even though the rules are already more restrictive than those found in most other free trade agreements.

The challenge facing Canada and Mexico will be to ensure that whatever emerges from the rules negotiating table doesn’t undercut NAFTA’s current benefits. Producers could decide that the new rules are too restrictive or burdensome, and opt to buy the materials they need from competitive offshore (non-North American) suppliers. They would pay the most-favoured nation (MFN) tariff on their exports to other NAFTA countries, but without the hassle of trying to abide by stiffer rules of origin.

Why do rules of origin matter? Using data from the United States International Trade Commission, I calculate that in 2016, half of Canada’s commercial exports to the United States entered duty-free by qualifying for NAFTA tariff preferences. Another 38 percent also paid no duties, entering under US MFN duty-free tariff lines. In cases where Canadian exports faced a positive MFN tariff, the use of the NAFTA preferential tariff was close to 80 percent overall — and rates exceeded 90 percent for some of our major goods exports, like autos.

Autos will be front and centre

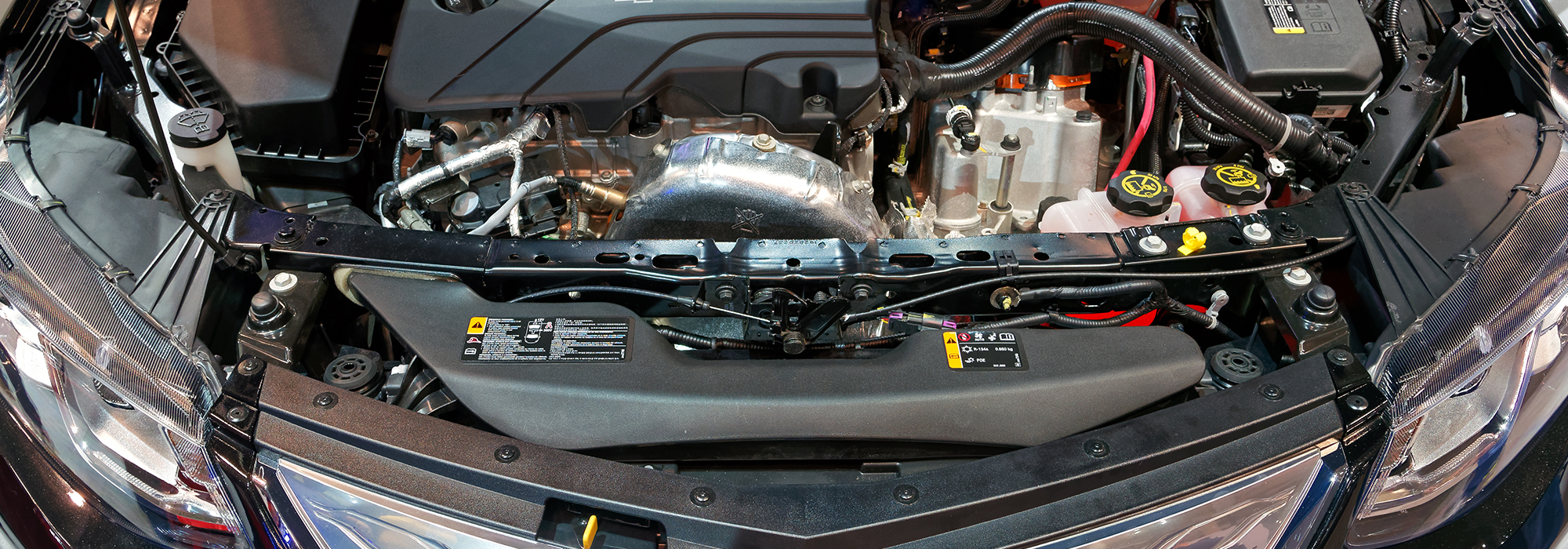

Indeed, the major negotiating focus around rules of origin will involve auto products — Canada’s largest manufacturing sector and export. As a result of NAFTA, the auto sector has become highly integrated across Canada, Mexico and the United States, with many parts crossing borders multiple times on their way to being assembled into a vehicle. Not only are approximately 85 percent of the light vehicles assembled in Canada exported to the US, but in 2016 they accounted for 16 percent of Canada’s total exports and 34 percent of Canada’s NAFTA exports to the United States. About half the value of Canadian auto parts production is also exported to the US, representing around 10 percent of Canada’s NAFTA exports. The use of the NAFTA tariff preferences is extremely high in this sector, at over 98 percent for vehicles and close to 90 percent for parts.

The Trump administration is expected to press to tighten the NAFTA rules of origin for autos, despite objections from the major American auto producers. American negotiators are likely to focus on raising the content level, which is currently 62.5 percent North American content for light vehicles and their engines, and 60 percent for heavy vehicles, their engines and all other auto parts. They are also expected to push to change the “tracing list,” which identifies which parts must originate in North America, and can thus be considered as using NAFTA regional content in rules of origin calculations.

While NAFTA’s restrictiveness has eroded over time because some new parts are not included in the 1994 tracing list, it still remains one of the most restrictive auto rule frameworks in the world. In their recent NAFTA submissions to the US Administration, the major North American assemblers, both US and foreign-owned, and the US parts producers, stressed the importance of not disrupting the existing complex trilateral supply chains. Similar views have been expressed in Canada by the Detroit three and Japanese assemblers. On the other hand, labour unions (UNIFOR and the UAW) have jointly called for “Made in North America” rules with higher content levels. The American Iron and Steel Institute wants steel added to the tracing list.

The Trump Administration’s need for a political win likely means the negotiations will result in a higher North American content level for autos, and an expanded tracing list. And there may be some limited scope for tightening the NAFTA auto rules of origin without causing a major disruption to the industry. However, care will be needed against going too far. Tightening the rules too much could backfire, as auto assemblers and parts producers can always opt out of exporting under NAFTA rules and simply pay MFN rates — for instance, the US MFN tariffs on light vehicles and most parts is only 2.5 percent. If auto producers sourced from offshore suppliers, it would be at a cost to US assembly and parts jobs. US-made parts account for around 40 percent of the value of vehicles assembled in Mexico.

Another scenario is that Mexican or Canadian car producers could relocate to the United States, the biggest North American car market. But there they would lose the competitive advantages of sourcing from the supply chains that weave across the continent. They would also face new duty-free competition in Canada from the European Union (EU) with the implementation of the Canada-EU Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA). The EU is negotiating with Mexico to expand its preferential market access under their existing FTA. And eleven of the TPP parties, including Japan, are exploring implementing the TPP without the United States. In short, retrenching to the US to manage a more costly, restrictive auto ROO does not automatically preserve their Canadian and Mexican markets.

Opportunities for Canada

While auto goods will be centre stage during the ROO discussions, the United States may also push to tighten the rules for other manufactured goods – for example, to require the use of North American steel aluminum.

The US textile sector wants to eliminate the special NAFTA Tariff Preference Level (TPL) provisions that allow annual fixed quantities of textile and apparel products from non-NAFTA countries to trade duty-free. This proposal, however, is expected to face strong opposition from US producers that use these provisions.

The NAFTA negotiations, nevertheless, offer Canada an opportunity to address concerns about the rules for specific goods, as well as seek ways to make them more flexible and less administratively burdensome. For example, crude oil accounted for 13 percent of Canada’s exports to United States in 2016; yet US$46 million were paid in US duties on 65 percent of these exports because non-originating diluent was used to enable bitumen to flow through the pipelines, thereby disqualifying the oil from NAFTA tariff preferences. The TPP included a fix for this problem, which Canada should pursue in the NAFTA negotiations.

Canada should also encourage its NAFTA partners to modernize the rules around other products, including chemicals, to make trade in these goods less administratively burdensome for both producers and customs officials. For instance, the Canadian government could push to simplify the way that the regional content of a good is calculated, so that the focus is solely on key components or materials (with the so-called “focused regional value-content method”). Canada has made such improvements in its more recent trade agreements since NAFTA, such as in the Trans-Pacific Partnership and the Canada-EU Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement.

The United States has indicated that it wants stronger enforcement of rules of origin, although it has not yet publicly offered specific reasons or proposals. Canada should be open to any reasonable proposal to ensure the rules are effectively enforced, but it needs to guard against US efforts to introduce aggressive enforcement methods that don’t include appropriate protections for the rights of producers, exporters and importers (such as the right of prior notification to verification visits by customs officials).

Trilateral “cumulation”

Another area where Canadian negotiators will be wary of changes is “trilateral cumulation.” This refers to the ability of producers to source, without restriction, duty-free materials and goods from any NAFTA country. This ability under NAFTA has fostered the growth of North American-wide supply chains in many industries, which have contributed significantly to both the increased competitiveness of North American producers and the economic benefits enjoyed by all three parties.

During the NAFTA negotiations, it will be essential for Canada and Mexico to resist any American demands that products contain a specific amount of US content. If the three parties were to impose country-specific (rather than continent-specific) content requirements, producers would have difficulty sourcing competitively priced inputs within North America. Their future competitiveness would also be further jeopardized if, in addition to having to bear the administrative burdens and costs of meeting three sets of country-specific content requirements, they also have to contend with more restrictive NAFTA rules of origin for their products.

The NAFTA modernization negotiations offer both challenges and opportunities for Canada on rules of origin. Canada’s economic interests call for liberalizing the rules to reflect the globalization of production since 1994. All of the other FTAs negotiated by Canada, Mexico and the United States in the last 15 years contain more liberal rules for the vast majority of products, including auto goods, than NAFTA. The TPP rules provide a model — indeed, the TPP offered significant economic benefits from its more liberal rules and full cumulation across its 12 members.

But the US administration’s anti-globalization and populist tendencies likely mean there will need to be some tightening of the NAFTA rules of origin, at least for specific products like auto goods. Canada and Mexico should strive to minimize any tightening, as well as stop any attempt to limit or disrupt trilateral cumulation under the NAFTA rules given the importance of the North American supply chains. Canada should also seek to address its priorities, such as the crude oil rules, and take any opening to liberalize the rules for specific products or reduce the administrative costs and complexity of the NAFTA rules of origin.

This article is part of the Trade Policy for Uncertain Times special feature.

Photo: Shutterstock/Zoran Karapancev

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.