(Version française disponible ici)

Birth tourism has risen to pre-pandemic levels after it dropped in half during the shutdowns of COVID-19. In the U.S., Donald Trump has set about trying to end birthright citizenship. What impact his plan might here have remains to be seen. But birth tourism is an issue the next federal government may need to re-examine.

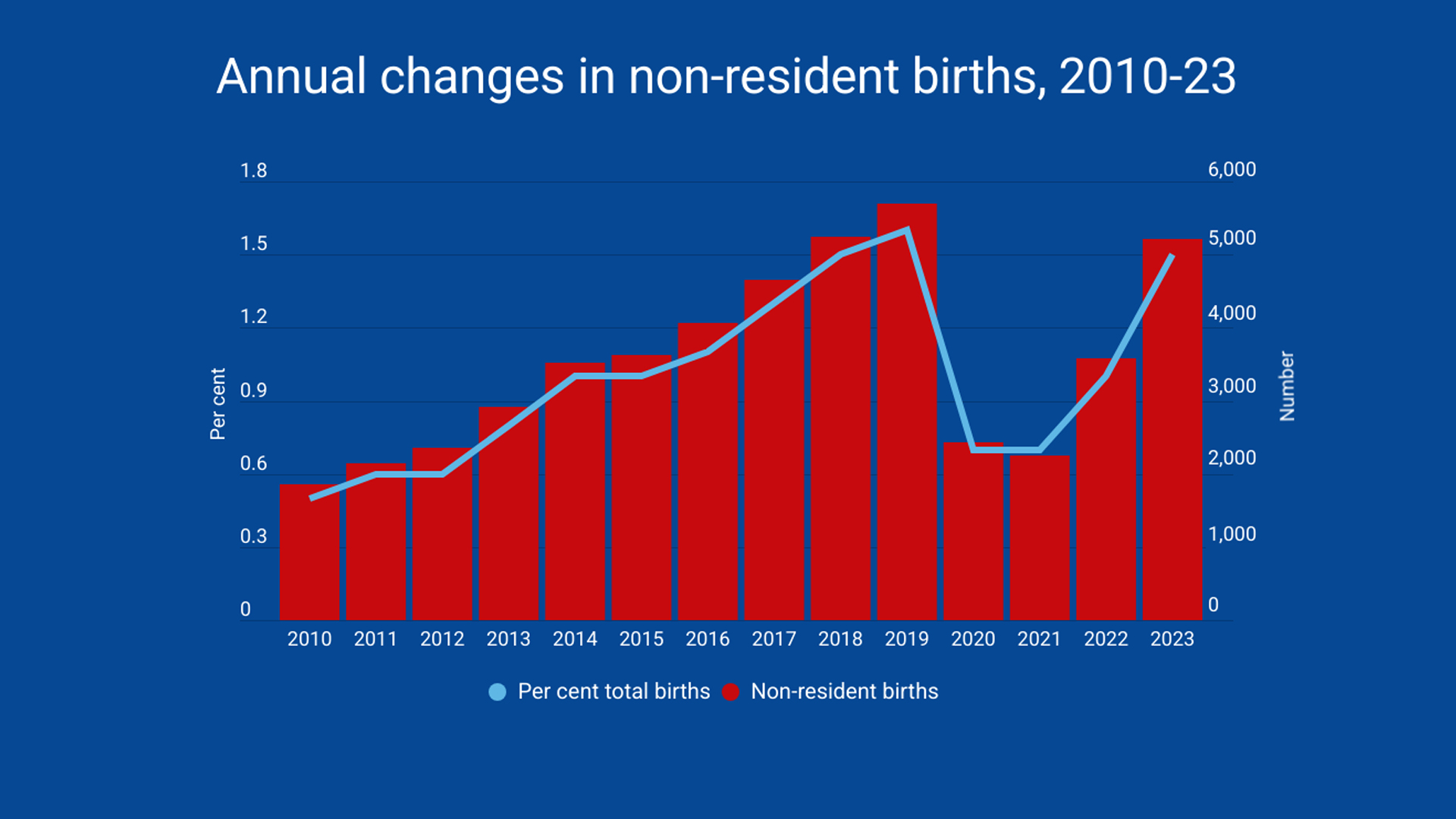

In 2024, tourism births across all provinces grew to 5,219, according to estimates tracked annually. That’s more than double the annual average during the pandemic. Birth tourism secures citizenship for children born to non-residents who travel to a country specifically to give birth there. Estimates are based on the number of “non-resident self-pay” births.

Ontario’s share has remained relatively constant over the years, averaging 53 per cent. But the shares of other large provinces have varied significantly: Quebec, between 20 and 33 per cent, British Columbia, between five and 15 per cent, and Alberta, between four and eight per cent.

Anecdotally, a similar decline in visitor visas and birth tourists has been noted in the U.S. though no recent post-pandemic data or articles exist. However, since January 2020, the U.S. has not issued visas “for birth tourism (travel for the primary purpose of giving birth in the United States to obtain U.S. citizenship for their child).”

Further restrictions are possible as Trump acts on his long-promised pledge to end birthright citizenship, though his executive order already faces court challenges.

The non-resident self-pay code used in this analysis is broader than that for women who arrive on visitor visas as it includes international students, about half of whom are covered by provincial health plans, and other temporary residents. The recently announced reductions in the number of international students and temporary workers will provide another natural experiment by comparing declines of these groups with an overall increase or decrease in 2024-25.

Visitor visas for Chinese nationals, one of the major groups, declined by 30 per cent during the same period. Chinese government travel-related restrictions were likely a significant factor. Visas for citizens of other countries that have been the subject of studies or anecdotes have increased substantially: Nigeria (343 per cent) and India (97 per cent).

Overall, about 50 per cent of non-resident births are estimated to be birth tourists.

While the percentage of non-resident births fell from 1.6 per cent of total births in 2019-20 to 0.7 per cent in 2020-22, it has rebounded to 1.5 per cent in 2023-24. Rising visitor-visa numbers help explain why in 2023 the total more than doubled to 1.2 per cent from 0.5 per cent in 2021. However, that was still significantly lower than the peak of 1.7 per cent of immigrants in 2019.

(The issuing of visitor visas increased by close to 900 per cent compared to 2020-21, the height of the pandemic. It rose 71 per cent compared to 2019-20, pre-pandemic.)

A hospital-level view of the impact of COVID over the last five years tells a revealing story when compared with pre-pandemic numbers at the 10 Canadian hospitals with highest percentage of non-resident births. While the percentage of non-resident births has increased in all hospitals from the pandemic year of 2020-21, only three Ontario hospitals have shown an increase compared to the pre-pandemic year of 2019-20.

Data provided by the Canadian Institute for Health Information does not provide a clear portrait of exactly where those who participate in birth tourism come from. However, in ridings where hospitals are located, the presence of services likely to support birth tourism can offer clues.

That was the case in Richmond Centre and appears to be the case in a recent Calgary study.

The Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada said in 2023 that birth tourism merits further investigation, but in an initial review it acknowledged “the absence of consistent data nationwide has hindered the ability to draw a complete picture using evidence-based analysis.”

Birth tourism is rising again post-pandemic

Bill C-71 opens up a possible never-ending chain of citizenship

Birth tourism in Canada dropped sharply once the pandemic began

There is a need for more hospital-level studies like one done in Calgary for 2019-20, particularly in hospitals that have more than five per cent non-resident births. Plus, the development of links between immigration and health data would allow for disaggregation of international students and temporary workers from the overall number of non-resident self-pay births, with those on visitor visas being the main remainder.

Donald Trump’s executive order will likely provoke Canadian commentary and advocacy that could pressure the next Canadian government to evaluate the need for new limits on birth tourism, something the Conservatives promoted in 2012. Today, they can develop a clearer picture of the situation by linking health and immigration data, a contrast to the largely anecdotal analysis conducted more than 10 years ago.

For matters of citizenship, the U.S. has its 14th Amendment. But Canada doesn’t have such a legal framework. Given the complexities of the issue, the Citizenship Act could mirror Australia’s approach, whereby newborns receive automatic citizenship or permanent residency only if at least one parent already has that status.