The COVID-19 pandemic provided the perfect natural experiment to assess the extent of birth tourism in Canada.

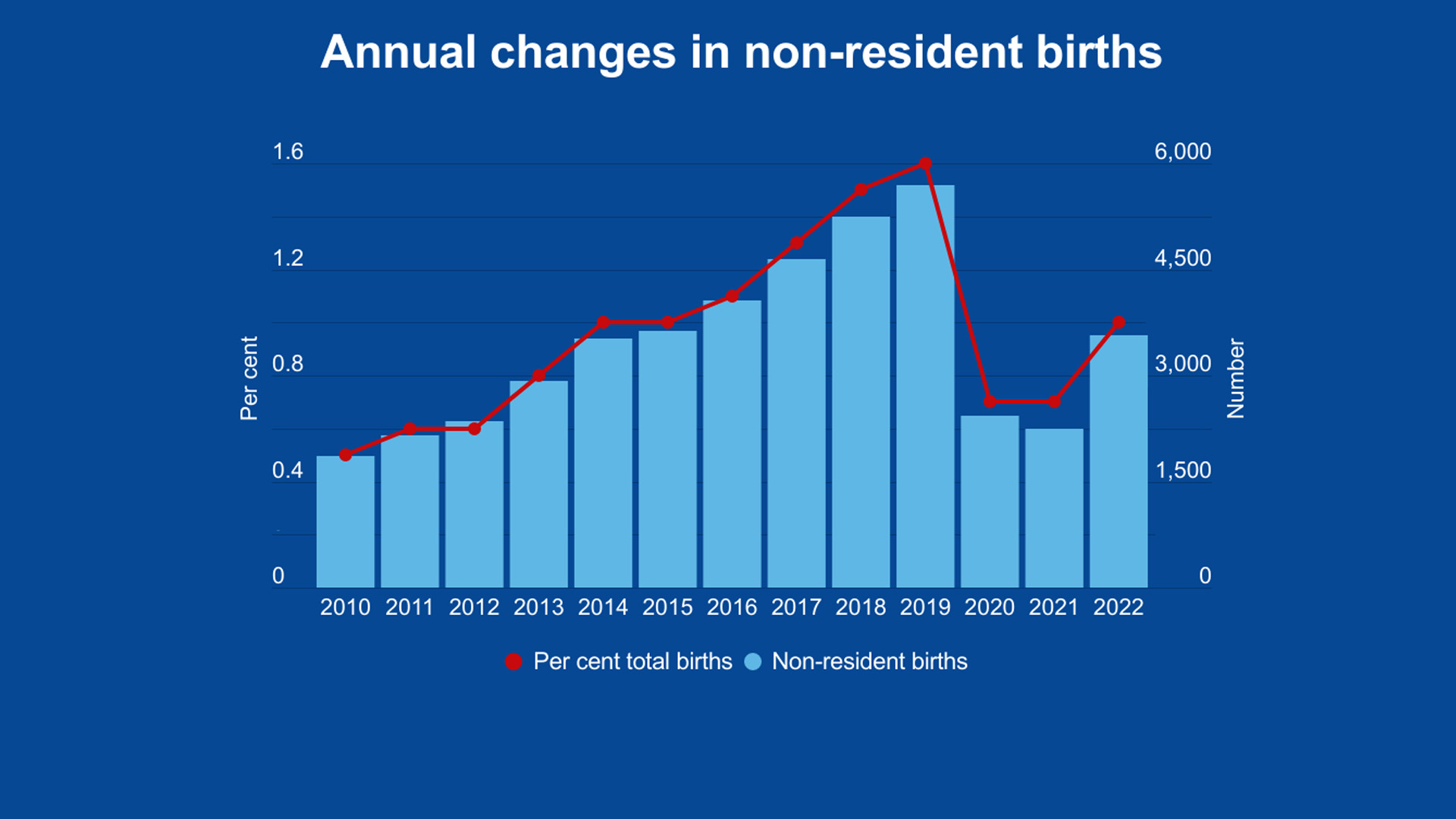

Dramatic declines of 50 per cent compared with the pre-pandemic 2016-20 average occurred in 2020 and 2021 in the number of “non-resident, self-pay” births. That was followed by an overall increase of 53 per cent in 2022 compared with the 2020-21 average, although the 2022 figure is still far below the 2019 peak.

This partial return to growing numbers highlights the need for the government to make good on its 2018 commitment to get a better handle on the extent of birth tourism, and to go so far as to consider an amendment to the Citizenship Act.

Figure 1 captures the steady increase prior to the pandemic and the sharp fall thereafter. Last year’s increase to 3,575 non-resident births from the pandemic average of 2,339 occurred in all provinces.

Table 1 compares non-resident births in 2011-15 and 2016-20 with those in subsequent years. The increase over these five-year periods contrasts with the sharp decline in 2020-21 and the sharp reversal in 2021-22, both of which were particularly notable in British Columbia. Compared to the 2019 high, the number of non-resident births has rebounded to 63 per cent of pre-pandemic levels.

There is no comparable U.S. post-pandemic data because since January 2020, the U.S. no longer issues visas “for birth tourism (travel for the primary purpose of giving birth in the United States to obtain U.S. citizenship for their child).”

Because there is no health-specific code for women travelling to Canada on visitor visas for birth tourism, the broader non-resident self-pay code is used. However, this includes international students, about half of whom are covered by provincial health plans, and other temporary residents.

Overall visitor visas in 2022 largely rebounded to pre-pandemic levels. The number of temporary workers has increased significantly. However, this varies by country.

Overall visitor visas for Chinese nationals used to be one of the major groups for birth tourism, but they have fallen dramatically. Chinese government travel-related restrictions are likely a significant factor in the reduction in Chinese birth tourists.

The percentage of non-resident births fell from 1.6 per cent of total births in 2019 to 0.7 per cent in 2020 and 2021, but it rebounded to 1.0 per cent in 2022. About 50 per cent of non-resident births are estimated to be birth tourists.

Table 2 provides a view of the impact of COVID-19 on non-resident births for the 10 hospitals in Canada with larger percentages of non-resident births. Since the dramatic fall during the pandemic, non-resident births have increased in most hospitals.

British Columbia’s Richmond Hospital was once the epicentre of birth tourism with its supportive “cottage industry” of “birth hotels.” In 2019-20, non-resident mothers made up 24 per cent of its births. But it fell sharply in this category during the pandemic and has rebounded only to four per cent in 2022. It’s now fourth in the Top 10.

The new No. 1 and No. 2 are Toronto’s Humber River Hospital, with 10.5 per cent of all births being non-residents and Montreal’s St. Mary’s with 9.4 per cent. Humber River is also the only hospital that showed an overall increase compared to pre-pandemic period.

There is a need for more hospital-level studies such as the one in Calgary that found about one-quarter of non-resident women who gave birth in the city in 2019-20 were from Nigeria. The study also estimated the cost to Alberta taxpayers.

The development of links between Canadian immigration data (e.g., immigration program and category) and Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) health data on medical services should allow for greater precision about the number of women giving birth while on visitor visas and those under other temporary resident categories.

Is birth tourism about to return now that travel restrictions have been lifted?

Birth tourism in Canada dropped sharply once the pandemic began

Overall, the federal government has not followed up on its 2018 commitment to “better understand the extent of this practice as well as its impacts” following the first release of the non-resident self-pay numbers and related media attention. The 2021-22 decline understandably reduced political interest and pressure in addressing the issue.

Given current and planned increases in immigration, it is highly unlikely that the government will act because the number of non-resident births is basically a rounding error compared to overall immigration of 500,000 a year by 2025.

However, as visitor visas largely reverted in 2022 to pre-pandemic levels, it is no surprise that non-resident births, including birth tourism, have increased. The government should resume work to clarify the issue. In particular, it should link immigration and health data to improve understanding of immigration and health issues, including birth tourism. As numbers of non-resident births can be expected to increase further, greater precision regarding the components of non-resident births would inform possible policy and program responses.

A 2019 Angus Reid survey found that 64 per cent of those Canadians surveyed would support a change in the law so that citizenship is not conferred on babies born here to parents on tourist visas.

Policy and operational questions remain about whether birth tourism warrants an amendment to the Citizenship Act, visa restrictions on women intending to give birth in Canada, or other administrative and regulatory measures to curtail the practice.

Visa restrictions would be difficult to administer and regional administrative and regulatory measures might encourage hospital and jurisdiction “shopping.”

So the cleanest approach would be an amendment to the Citizenship Act that would require one parent to be a citizen or permanent resident of Canada. That is the situation in Australia.

Should the Conservatives form a government after the next federal election, they may well decide to revisit the issue of birth tourism given that the Harper government pressed the issue in 2012 only to back off.

A note on methodology

The data is from the CIHI’s discharge abstract database, more specifically “non-resident self-pay” category in the responsible for funding program (RFP), as well as totals for hospital deliveries.

The overall RFP data includes temporary residents on visitor visas, international students, foreign workers and visiting Canadian citizens, and permanent residents. Quebec has a slightly different coding system, but CIHI ensures its data is comparable. Data for Quebec hospitals is not provided through CIHI and thus the larger Montreal area hospitals were approached directly.

Ottawa-area hospitals were not included given the number of diplomatic families likely being a substantial portion of non-resident births. Declines in non-resident births at Trillium-Credit Valley Hospital in Mississauga, Ont., led to that hospital falling off the Top 10 list.

Health coverage for international students varies by province, but most of them are covered by provincial health plans. This is not the case in Manitoba and Ontario, as well as for some students in Quebec if their country of origin does not have a social-security agreement with Quebec. The pre-pandemic baseline is the five-year average 2016-20.

Mackenzie Health’s woman and child program moved from Mackenzie Richmond Hill Hospital to Cortellucci Vaughan Hospital when it opened to the community in June 2021.