The COVID-19 pandemic provides a perfect natural experiment to assess the extent of birth tourism in Canada now that we have 2020-21 hospital delivery data from the Canadian Institute of Health Information (CIHI).

The latest data respond to questions regarding the accuracy of CIHI data in assessing the extent of birth tourism following my initial analysis in 2018 in Policy Options, given the correlation between visitor visa data and the sharp drop in birth tourism. Moreover, given the cost of coming to Canada for the purpose of giving birth, they also demonstrate that the nonresident women who give birth are largely the economically privileged rather than the more economically vulnerable.

The 2020-21 data show that “nonresident self-pay” births declined by 57 per cent compared with the previous year, from 5,698 to 2,433 for all provinces, including Quebec. While this category is broader than that of women who arrive on visitor visas, visitor visas issued declined by 95 per cent, compared with the proportion of international students, which declined by only 25 per cent (most provincial health plans cover international students), or temporary workers, which actually increased by 5.5 per cent. As Canadian citizens and permanent residents were largely exempt from COVID travel restrictions, the number who chose to return to Canada to give birth is likely unchanged.

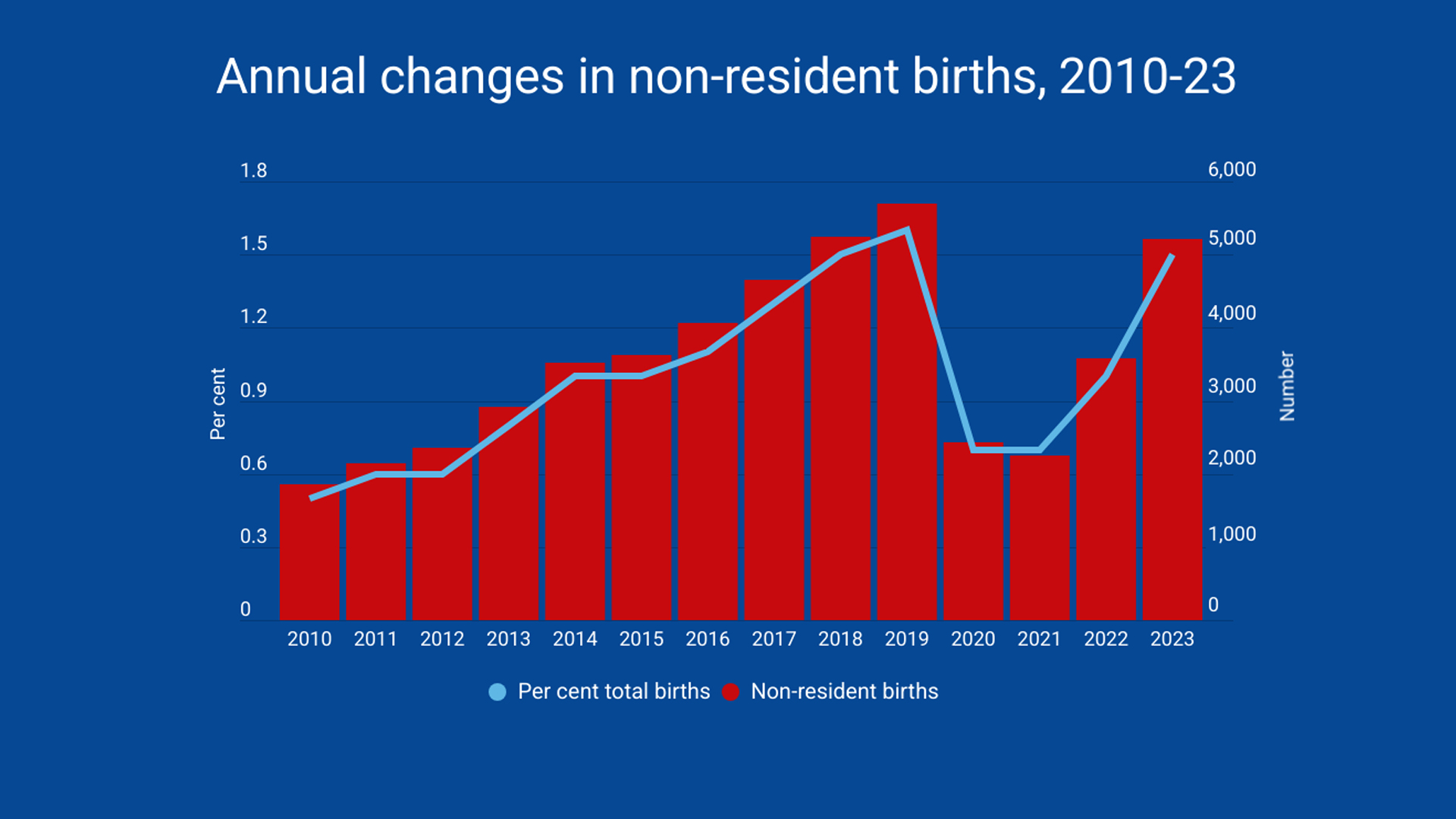

Figure 1 contrasts the steady rise in nonresident self-pay births over the past 10 years and the sharp drop in 2020-21 back to 2010-11 levels. The percentage of nonresident births fell from 1.6 per cent of total births in 2019 to 0.7 per cent in 2020.

Table 1 compares nonresident births in 2011-15 and 2016-20 with those in 2020-21 and the change that occurred. The steep increase over these five-year periods contrasts with the sharp decline in 2020-21, which was particularly notable in British Columbia and Alberta.

Table 2 provides a hospital-level view of the impact of COVID, contrasting pre- and post-pandemic years in terms of nonresident and total births for the 10 hospitals with the largest percentage of nonresident births. Nonresident births declined dramatically in all hospitals; British Columbia’s Richmond Hospital, the epicentre of birth tourism with its supportive “cottage industry” of “birth hotels,” was one of the strongest hit.

This suggests that my initial estimate that about 50 per cent of nonresident births were due to birth tourism was conservative, and that the percentage of “tourism births” is about 1 per cent of all births (or about 0.4 per cent of current immigration levels).

Unfortunately, the government appears to have dropped its 2018 commitment to “better understand the extent of this practice as well as its impacts” following the release of the CIHI numbers and related media attention. Given the expected reversion to growth in birth tourism, the government needs to resume work in this area, particularly with respect to linking immigration and health data, in order to improve understanding of immigration and health issues, including birth tourism.

The policy and operational questions remain as to whether the extent of birth tourism warrants an amendment to the Citizenship Act, visa restrictions on women intending to give birth in Canada, or other administrative and regulatory measures to curtail the practice. As visa restrictions would be difficult to administer, and regional administrative and regulatory measures may well encourage hospital and jurisdiction “shopping,” the “cleanest” approach would be an amendment to the Citizenship Act that would require one parent to be a citizen or permanent resident of Canada, comparable to the situation in Australia.

Although the previous Conservative government explored a legislative change in 2012, this was abandoned given provincial opposition and the costs involved. However, at the time, the number of birth tourists was estimated at 500, much lower than what is shown in the more accurate data we have now.

As travel restrictions continue to ease, we can expect the number of nonresident births and birth tourists to revert to their previous growth. Should this happen, it will prompt further calls to restrict birth tourism. The 2019 Angus Reid survey indicated that the vast majority would support such a change for women on visitor visas.

This COVID-19 pandemic “natural experiment” demonstrates that birth tourists form more than the majority of nonresident births and is trending upward. Further discussions and debates should recognize this reality.

A note on methodology

The data is from the CIHI’s Discharge Abstract Database, more specifically the Responsible for Funding Program (RRFP) “non-resident self-pay” category, as well as totals for hospital deliveries. The RRFP data include temporary residents on visitor visas, international students, foreign workers and visiting Canadian citizens, and permanent residents. While Quebec has a slightly different coding system, CIHI ensures its data is comparable.

Health coverage for international students varies by provinces, but most are covered by provincial health plans. This is not the case in Manitoba and Ontario.