Readers of 20 regional newspapers in the UK have been unwittingly involved in what was called a first for journalism. At the end of 2017, a bunch of stories published in these dailies and weeklies were written by algorithms, rather than humans.

The stories reported on trends in birth registrations across the UK drawn from data from the Office of National Statistics, such as how many children were registered by married, cohabiting or single parents. But each individual story gave the figures a local twist. The trial was part of a project by Press Association, the UK’s equivalent of The Canadian Press news service. It hopes to automate some of its journalism and pump out 30,000 news stories a month tailored for local audiences.

Robojournalism of this kind is one of the most visible signs of how artificial intelligence (AI) is rewriting journalism. It highlights how code, written by humans, structures ways of knowing.

The benefits of robojournalists are obvious. Algorithms can generate routine stories faster, cheaper and at greater scale than people, potentially expanding coverage and opening up new sources of revenue for a beleaguered industry. They work best with clear and structured data, such as in financial and sports news. The Associated Press, Reuters and AFP are already churning out thousands of automated stories a year.

We may be sleepwalking toward a future where AI systems dominate digital communications.

But robowriting is only the tip of the iceberg that is artificial intelligence. This is not an iceberg in the distance, but one that is here now. We may be sleepwalking toward a future where AI systems dominate digital communications.

AI is fast becoming embedded in the fabric of daily interactions, from navigation apps that optimize driving times to product recommendations based on past purchases; from the algorithms filtering Facebook’s news feed to digital assistants like Siri. Imagine having your very own Peter-Mansbridge-voiced AI system recommending and reading a news bulletin for an audience of one on your home smart speaker.

Artificial intelligence is rewiring the news and information ecosystem in novel and unexpected ways, just as past technologies such as the printing press or the telegraph reshaped the media landscape. New technologies open up new avenues for both creativity and manipulation.

Media organizations are taking note. Some 75 percent of publishers are already using AI in some form, according to a Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism survey. Algorithms are recommending and tailoring news content online, responding to a reader’s preferences and habits. The technology is helping journalists detect breaking news events quickly by monitoring and analyzing chatter on social media.

In China, a world leader in AI research, the state news agency is going farther. The Xinhua News Agency plans to put AI at the core of its journalism, with the aim of building “a new kind of newsroom based on information technology and featuring human-machine collaboration.”

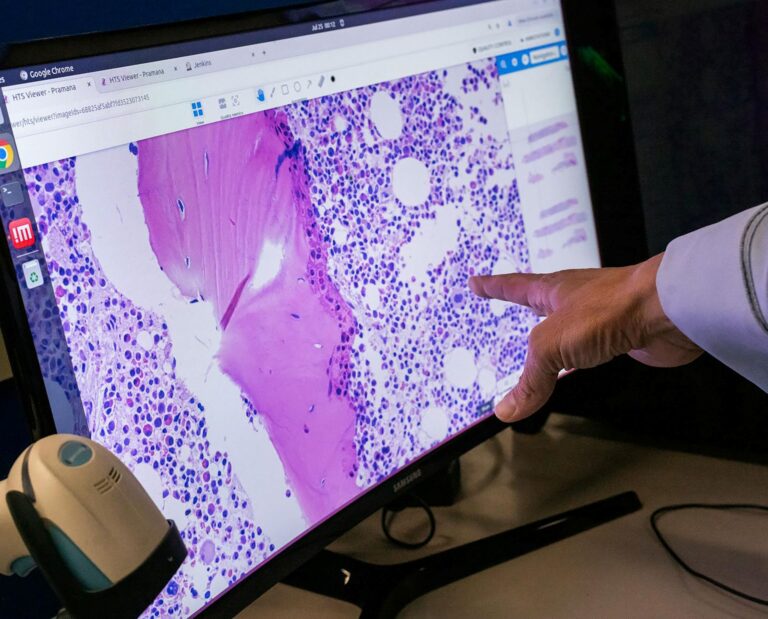

Computational tools are also being harnessed as tools of accountability by newsrooms, using the technology to swiftly analyze vast amounts of data. Work is in progress on developing AI systems to help journalists fact-check politicians in real time, with the aim of combatting misinformation.

The furor over fake news of the past year pales into insignificance beside the prospect of neural networks able to post phony Yelp reviews or synthesize images and videos that are indistinguishable from the real thing.

The same technologies, though, can be used to produce and spread misinformation. The furor over fake news of the past year pales into insignificance beside the prospect of neural networks able to post phony Yelp reviews or synthesize images and videos that are indistinguishable from the real thing. A fake Barack Obama speech created by researchers at the University of Washington last year showed how far the technology has come. Seeing is no longer believing.

Robojournalism seems child’s play compared with the potential of the technology. Nicholas Diakopoulos, an assistant professor of communication at Northwestern University, warns of an AI arms race for authenticity: a computational contest between those using AI to spread misinformation and those seeking to develop automated defence mechanisms to identify half-truths and distortions and purge them from the Internet. The outcome is too important to be left to technologists to decide.

Artificial intelligence networks are infrastructures of knowledge, built on the views, values and visions of their builders. Buried in algorithms are hidden biases. Automated news stories are based on editorial choices embedded in code that assign importance and relevance to certain facts and figures. The story may have been written by an algorithm, but a human programmed it.

The era of AI heralds a new phase of disruption for the media. For journalists, it means becoming fluent in AI, understanding how to deploy new tools for ethical and responsible storytelling. For media organizations, there are new opportunities in how news is reported, produced and discovered. But there are also new ways to subvert the media and circulate fake news.

How AI is reshaping media is an issue that goes beyond journalism. Politicians and regulators face a rapidly evolving and increasingly complex media ecosystem where the speed and complexity of technological development far outstrips the pace of policy development. Policy-makers, technologists, researchers and journalists need to collaborate now — to brace for the societal impact of AI and identify opportunities and solutions — rather than lamenting the consequences in the years to come.

This article is part of the Ethical and Social Dimensions of AI special feature.

Photo: Shutterstock

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.