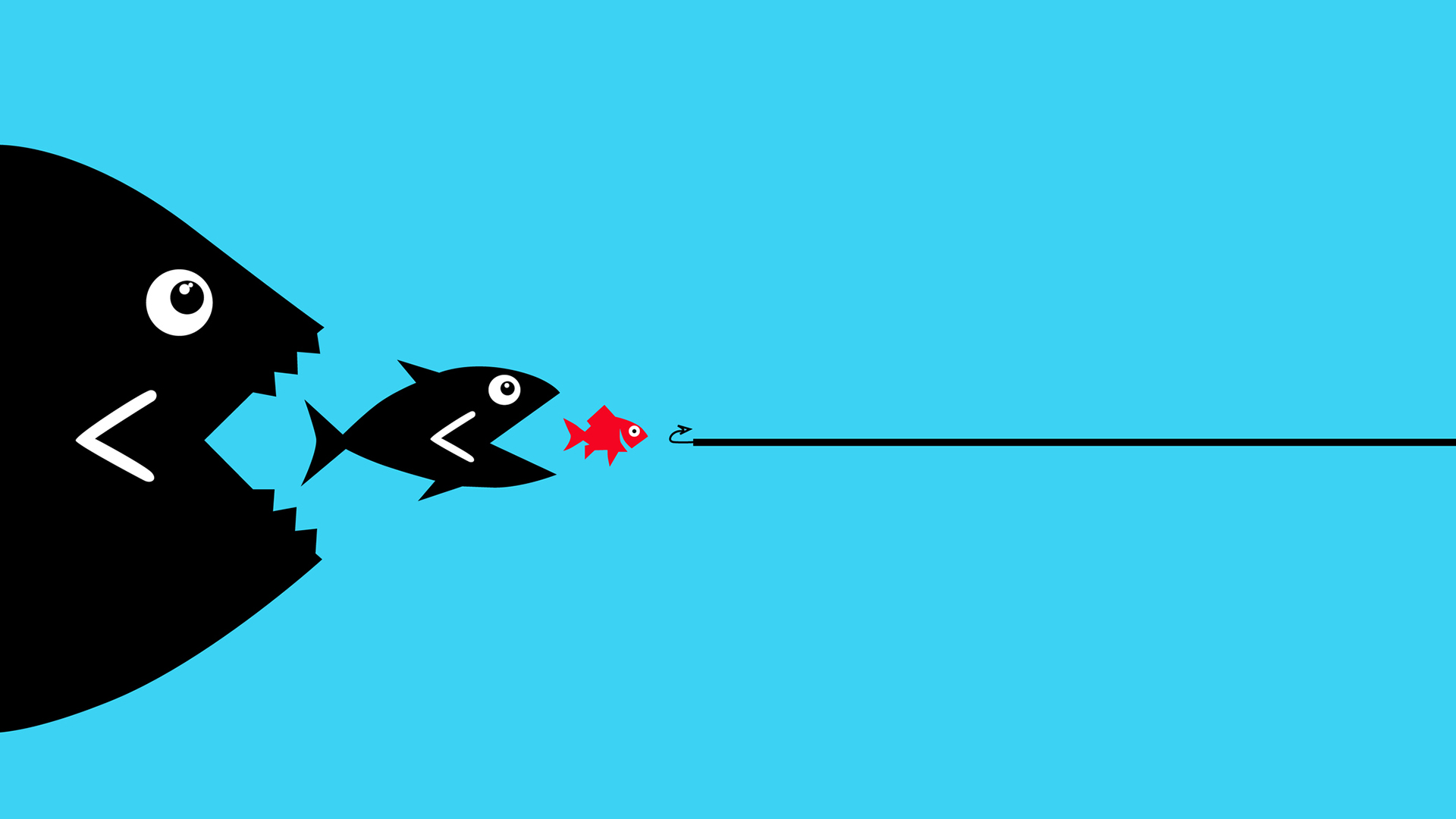

Canada’s rethinking of its trade relationship with the United States is a monumental undertaking that needs to start with our competition policy and its contradictory aims. If we want a dynamic and resilient economy, we need less concentration in markets by a handful of companies.

Replacing the 1985 Competition Act with a law more focused on promoting competitiveness would be a good place to start.

Canadians are increasingly frustrated with a lack of competition in industries where as few as two or three major players dominate the market. For example, 92 per cent of respondents in a 2023 poll said corporate concentration was affecting the prices of groceries and telecommunications services. Only seven per cent said they believed Canada’s current competition laws benefit consumers, while 69 per cent felt they benefit corporations.

Canadians were paying 170 per cent more in 2023 for their cellphone plans than Australians and 20 per cent more than Americans. Not surprisingly, Bell, Rogers and Telus at that time owned 90 per cent of Canada’s telecom market. They are still the predominant telecom providers.

On the groceries front, over 100,000 people are members of a Reddit subgroup (r/LoblawsIsOutOfControl) where they share their frustrations over high prices. A few chains, including Loblaw, Sobeys and Metro, have gained control of a large share of the market by taking over their competitors.

Clashing goals

Canadian competition law began in 1889, when the government passed the first antitrust statute in the industrial world. But the law provided few means to enforce it and did not result in any convictions in its early years. There were repeated attempts for a century to either replace or reform the law.

The most important reforms took place in the 1980s following the enactment of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Beginning with the Liberals, these efforts intensified under Brian Mulroney’s Progressive Conservative government during its attempts to loosen trade and investment restrictions. In 1986, the Competition Act became law.

The preamble of the Competition Act says its purpose is to maintain and encourage competition so as to:

- Promote the efficiency and adaptability of the Canadian economy.

- Expand opportunities in world markets while at the same time recognizing the role of foreign competition.

- Ensure small- and medium-sized businesses an equal opportunity in the economy.

- Provide consumers with competitive prices and product choices.

Speeches by government members in the House of Commons already showed views that implied tension between these goals. MP John Gormley said that the “law [recognizes] that in some instances concentration may be necessary (italics mine) to make Canadian industry world competitive to the benefit of consumers and businesses all across our country.” MP Donald Blenkarn said that “mergers and acquisitions which will assist Canada in its international dealings will be allowed (italics mine) to take place.”

It was already clear that in cases where the second and third goals listed above clashed, promoting Canadian participation in world markets would be given priority.

The Competition Act must be understood in the context of Mulroney’s efforts at trade liberalization. The government had plans to increase free trade between Canada and the U.S. and felt that allowing further corporate concentration was an important part of ensuring this would happen.

One Canadian economy needs one competition policy

Trump’s tariff threats expose Canada’s internal monopoly problem

Michel Côté, who as minister of consumer and corporate affairs was responsible for passing the bill, argued it was the “cornerstone of … government initiatives designed to make Canada competitive internationally.” Members of the academic business community argued that the only way for Canadians to free themselves from U.S. domination was to allow the government to set industry standards under monopoly conditions.

Competitive domestic markets were sacrificed with the hope that this would make Canada a bigger trading force on the world stage.

There are two reasons why this approach has proven to be short-sighted.

First, some of today’s worst industries for competition do not compete internationally. Canadians pay some of the highest telecom bills in the world to Rogers and Bell, two companies without significant footholds in other countries. Instead, they squeeze Canadians for as much as they can.

Second, while relaxed antitrust and merger standards may let existing companies compete in international markets, it can hurt Canada’s overall competitiveness by stifling innovation. How many billion-dollar companies has Canada lost from acquisitions or entrenched market dominance by others?

Maybe if Ontario-based electronics corporation ATI Technologies had remained independent, it could have found a way to get a slice of computer chip giant Nvidia’s global pie. Or if marketing automation platform Eloqua, founded in Toronto, hadn’t been bought by U.S-based Oracle, its growth might have been more centred in Canada.

Reform of the Competition Act has begun. Section 96 became such a target of criticism that in 2023, the Conservatives, Liberals and NDP all put forward bills to remove it. Section 96 allows companies to merge if gains from efficiency are found to be greater than the loss in competition. The Liberal bill officially became the Affordable Housing and Groceries Act. The legislation, among other things, removed the efficiencies defence from the Competition Act.

But the problem with our competition policy is not one clause. It’s the whole act trying to function as both competition law and industrial policy. If you chase two rabbits, you will not catch either one.

Prioritize domestic markets

What Canada needs is a policy focused squarely on promoting competition domestically rather than one focused on the global economy. This would increase innovation and give consumers more choice by ensuring that small and medium enterprises could compete on a fair playing field. It could also potentially help with Canada’s declining productivity.

Former prime minister Pierre Trudeau once noted that existing “next to (the U.S.) is in some ways like sleeping with an elephant. No matter how friendly and even-tempered is the beast … one is affected by every twitch and grunt.” For 40 years, Canada has tried to protect itself from the elephant through our own economic behemoths, for example, allowing Loblaw to buy up its competitors for fear of U.S. corporation Walmart, much to the detriment of Canadian consumers.

The elephant is doing more than twitching and grunting as U.S. President Donald Trump maintains his aggressive stance toward Canada’s economy. With Canadians looking to buy Canadian, it’s the perfect time for a revamped policy actually focused on competition. Rewriting the legislation with fewer loopholes and exceptions — while strengthening enforcement mechanisms — would go a long way.

Instead of seeing Canada’s smaller economic size relative to the U.S as a disadvantage, proper competition laws could allow us to embrace a more dynamic and nimble economy. In this way, living next to an elephant could perhaps become a less uncomfortable bed to be in.