(Version française disponible ici)

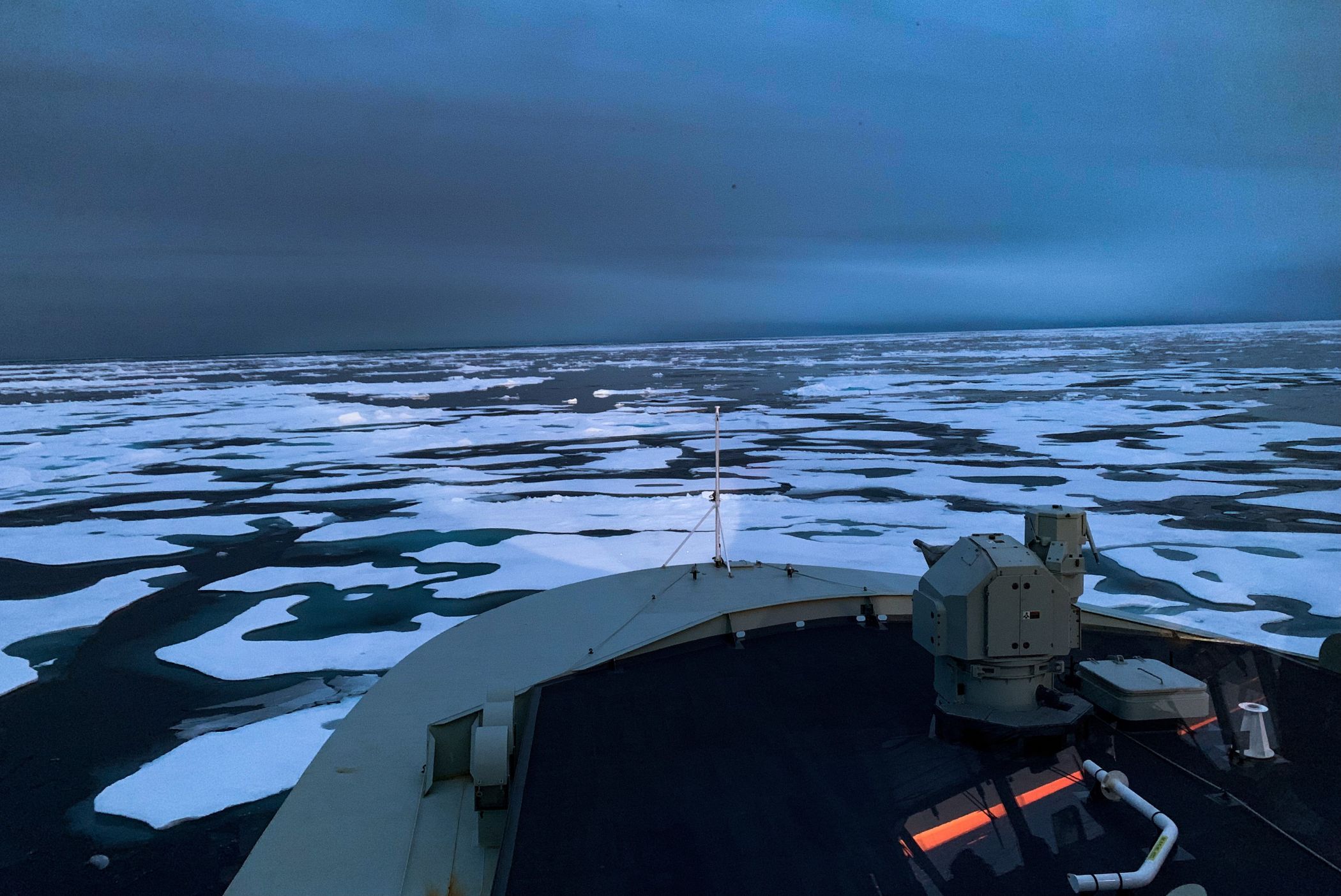

By 2027 the Arctic Ocean could be completely ice-free. Where the Arctic Circle was once frozen year-round, navigable by only a few icebreakers and submarines, it will soon be able to host a diverse array of surface vessels.

As the retreating sea ice opens new shipping lanes that bypass the Panama and Suez canals, Canada’s Northwest Passage will become a contested commodity. Shaving some 7,000 kilometres from the journey between Asia and Europe, this corridor represents a lucrative opportunity for commercial shipping companies and the states which rely on them for trade.

U.S. President Donald Trump has made his position clear: America ought to reassert itself in the Arctic, even at the expense of longtime allies’ sovereignty, to secure its profitable shipping lanes and mineral resources for itself — a marked divergence from longstanding American policy.

Canada and the U.S. have for years been at odds over the status of the Northwest Passage. Canada has historically claimed the passage as an internal waterway, part of its sovereign territory, but the U.S. insists it is an international strait that foreign vessels have a right to travel through without Canadian oversight or interference. This is an extension of broader American foreign policy, where the U.S. views itself as a protector of freedom of navigation and free global commerce on the seven seas, enforced by its naval might.

Washington bases its role as a global maritime policeman on the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), which spells out laws governing the use of the world’s seas and their resources — including the right of vessels to travel freely through qualifying international straits.

American interests

The U.S. has a vested interest in preserving freedom on the seas. Its economy and standard of living are dependent on the enormous flow of durable goods that are transported by ship every day. American military power similarly rests on the ability to move naval assets quickly and lawfully around the globe.

American foreign policymakers have for decades viewed Canadian claims over the passage as being secondary to this imperative of preserving free global commerce and legitimizing U.S. naval operations.

Beyond protecting freedom of the seas, Washington also sees the Arctic as vital to its own “essential security interest”, and has repeatedly acted on that belief, sending vessels through the passage without Canadian permission in 1969, 1985 and again in 2005. That final transit, involving U.S. nuclear submarines, effectively revived sensitivities around the sovereignty issue, despite the 1988 Arctic Cooperation Agreement in which Washington agreed that its icebreakers should seek Canadian permission to transit the passage, and Canada agreed not to deny them.

America’s policy is clear and consistent, with both strategic and liberal justifications for its existence, but it also leaves itself in an odd position where the Arctic is concerned. The player most poised to benefit from Washington’s role, and exploit the fruits of a melting ice sheet, is not the United States, Europe or Canada.

Instead, it is China.

China’s Arctic advantage

Beijing has made the Arctic a strategic priority. Despite possessing no Arctic territory of its own and being thousands of kilometres away from the polar regions, China describes itself as a “near-Arctic state.” It has used this self-designation to justify its admittance to the Arctic Council as a permanent observer, and to make the region part of its strategic ambitions.

Chinese policymakers have been explicit about their intentions. The Arctic figures prominently in Beijing’s vision of a “Polar Silk Road,” an extension of the Belt and Road Initiative designed to help China project its economic might and political influence around the world.

This is not just rhetorical posturing. China has sent numerous research and commercial vessels through the region – including in the Northwest Passage – and has invested considerable funds into scientific infrastructure. One of its largest embassies is in Iceland, as it anticipates Reykjavik’s accession to a transatlantic commercial hub.

Beijing has committed this money and effort because it sees commercial and geopolitical advantage. Not only would polar sea lanes drastically reduce shipping times to European markets, the Arctic has an abundance of resources, including natural gas, on which China is increasingly dependent. Having more access to this region would be a massive boon to China’s global influence and economic growth.

Expanding its Arctic presence also lets China make Washington’s strategic position more complicated. In its determination to defend the freedom of the seas for commercial vessels under many different flags, the U.S. is also enshrining China’s right to utilize these shipping lanes in ways that strengthen Beijing’s global posture.

This U.S. insistence on open Arctic shipping does not evenly benefit all states, but disproportionately strengthens China. Even an “ice-free” Arctic still contains some hazardous ice, limiting all-season access to states that have advanced icebreaking capabilities. Few countries meet that threshold as well as China, which in recent years has built a fleet of state-of-the-art icebreakers.

Fewer still are as well positioned geographically to capitalize on a northern route. Export-oriented economies in Southeast Asia, Africa and Latin America remain far better served by routes through the Suez and Panama canals. The commercial upside of Arctic transit accrues overwhelmingly to Beijing.

While America’s defence of international maritime law is admirable, under the Trump Administration it remains unclear how much that will actually matter. From a raw geopolitical standpoint, the dispute over who owns the Northwest Passage is pitting the United States against a NATO ally, a dispute in which China ends up being the main beneficiary.

Regardless of the merits of its sovereignty claims, Canada on its own does not have the capacity to forcefully stop the U.S. or even its European allies from accessing the passage. Russia, meanwhile, can rely on its own polar sea routes.

Again, the only party left is China.

A strategic reassessment

Fortunately, American policymakers are not in a situation where they must choose between a fragmented liberal international order and a desire to contain China. Canada’s claim over the Northwest Passage is not a stalking horse for maritime revisionism.

The passage runs through a complex Arctic archipelago that Canada has historically governed, inhabited and administered. Prior to the 21st century, it had been transited fewer than 100 times — hardly the basis for being an “international strait” when UNCLOS came into force in 1994.

While technicalities of the issue can be argued extensively among legal scholars, the point remains that Canada’s claim to the passage is clearly plausible, in a way that Panama claiming sovereignty over the canal would not be. For both the U.S. and Canada, supporting Canadian sovereignty would not mean completely flouting international law. It is possible to credibly justify Canadian claims in the North while rejecting, say, Iranian claims to the Strait of Hormuz, which UNCLOS recognizes as an international waterway.

Canada’s next Arctic move: Look west

If U.S. policymakers view the Northwest Passage in a broader perspective, it becomes clear that America does not need to support Chinese access to the Arctic in order to remain consistent in addressing other maritime disputes. On the contrary, it is strongly in America’s interest to ensure that a strategically vital corridor remains under the control of its own northern ally and trading partner.

Washington can limit Beijing’s ability to exploit a new Arctic corridor without having to re-evaluate maritime doctrines elsewhere. In the case of the Northwest Passage, preserving the status quo of Canadian authority aligns with American interests. Keeping the region under the auspices of a longtime ally enables U.S. policy to be seen as upholding the rules-based order while also containing its main rival.

Granted, there’s a new wild card in all of this: the Trump Administration’s contempt for international laws and norms. Trump has brazenly attempted to coerce the EU and NATO into ceding Greenland to the United States. However, even in this, there is a certain irony. Under Trump, the U.S. is prepared to attack the sovereignty of a close ally — obstinately, in part, to control Arctic shipping — after decades of pressing Canada to weaken its control over the very same waters.

This is not a coherent Arctic policy. Either Chinese and Russian vessels have access to the Western Arctic under international law, or the U.S. must annex Greenland to prevent this very outcome. Neither of these conclusions may hold, but they cannot coexist. Trump does seem to genuinely consider a Chinese Arctic presence to be a large enough threat that he would torpedo America’s transatlantic relationships. In that context, and perhaps after more sober reanalysis, it is worth re-posing the central question: Why, then, does the United States align itself with China on the question of Arctic trade?