The capture of President Nicolás Maduro of Venezuela could give the United States access to the world’s largest reserves of heavy crude oil. This could become an important asset for the United States because many of its oil refineries were designed and built to process heavy crudes, not the light crudes now available from U.S. shale oil.

If the United States reduces its consumption of Canadian heavy crude oil, Canadian pipelines will need to be built or expanded to access other international markets. With U.S. President Donald Trump, however, there could be another wrinkle.

Historic supplies of heavy crude

The United States has become the world’s largest exporter of light crude oil because of its shale oil. The country is also now one of the world’s largest importers of heavy crude.

Throughout the 1980s and into the 1990s, Mexico, Venezuela and Canada were major exporters of heavy crude oil to the United States. In 1999, they each supplied the United States with about 1.2 million barrels a day.

However, since then, the supply of heavy crude from the three countries has diverged.

Mexico’s heavy crude exports to the United States peaked at 1.6 million barrels a day in 2004. They have declined steadily since then – the result of aging oilfields and mismanagement of Pemex, the Mexican state oil company, whose excessive debt became a burden to the state. On top of that, the construction of a heavy crude refinery, Dos Bocas, took a portion of Mexico’s production but has encountered operational setbacks. In 2024, Mexico exported to the U.S. only an average of 0.46 million barrels a day.

Venezuela’s supply of heavy crude oil to the U.S. peaked at 1.39 million barrels a day in 1997 – the year before Hugo Chávez was elected the country’s president. Under Chávez, production remained flat until 2007, when PdVSA (the Venezuelan state oil company, Petróleos de Venezuela S.A.) took a majority holding in four oil projects in the Orinoco basin.

The move prompted ExxonMobil and ConocoPhillips to quit the country. BP and Chevron remained as minority partners. The seizures of the assets of other companies followed over the next few years. After the death of Chávez in 2013, his successor, Maduro, continued to degrade Venezuela’s oil industry.

U.S. sanctions on Venezuela began in 2005, culminating in 2019 with the imposition of an import ban on Venezuelan crude oil imposed by Trump. Production has subsequently increased with the waiver of the sanctions by former president Joe Biden after lobbying by Chevron and a complete lifting of sanctions in 2024 with the (unkept) promise of free and fair elections later that year. Exports to the United States reached 0.24 million barrels a day in 2024.

(Investments by Chinese oil companies and other countries, including Russia and Iran, pushed Venezuela’s total production to almost one million barrels a day in 2024.)

As Mexico’s and Venezuela’s exports of crude oil to the United States fell, Canada’s increased. By 2024, Canada’s exports of both heavy (less than 25° API) and lighter (greater than 25° API) crudes reached almost 4.1 million barrels a day thanks to more production from Alberta’s oilsands.

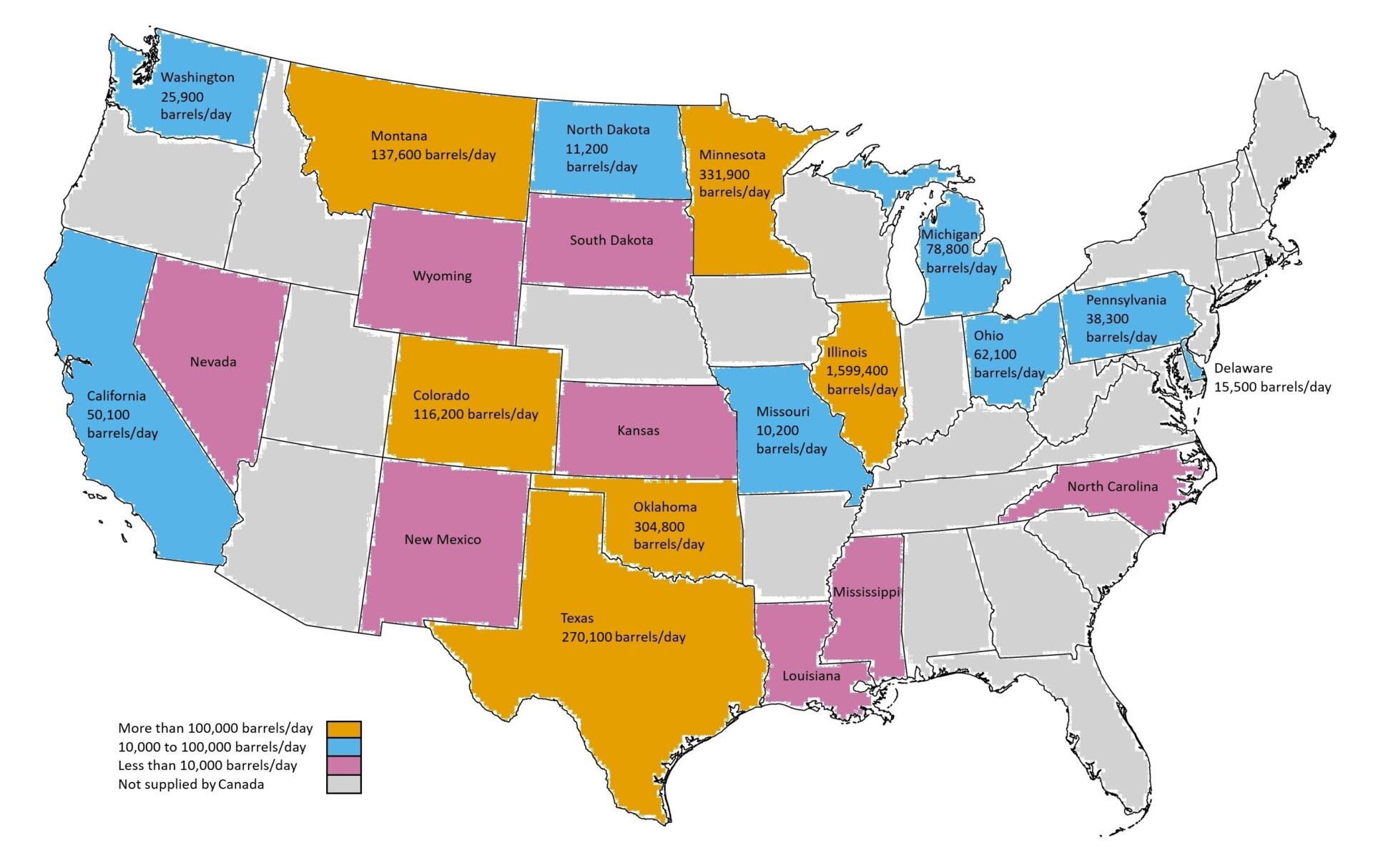

In 2024 (the last full year for which data is available), Canada exported about three million barrels a day of heavy crude to refineries in 23 U.S. states. Most of it came from Alberta. Of these, nine states used 10,000 barrels or less a day. Another eight states received between 10,000 and 100,000 barrels of heavy oil a day. The remaining six states received more than 100,000 barrels a day. Of all the states, Illinois used the most, almost 1.6 million barrels a day.

Figure 2: Daily consumption of Canada’s heavy crude oil by state

Source: Data from CIMT. Base map from vemaps.com)

Scenarios for Venezuelan crude

Trump has said the capture of Maduro and his wife in early January could lead to an increase in Venezuela’s heavy oil exports to the United States. Some analysts say it will take years and cost tens of billions of dollars before any crude flows to the United States. But it could occur more quickly.

In 2024, Venezuela produced about 0.96 million barrels of crude a day. Most of the crude was shipped to four countries: China (68 per cent), United States (23 per cent), Spain (four per cent) and Cuba (four per cent). Venezuela also used a shadow fleet of tankers, some of which have been intercepted and impounded by the United States, while other tankers are stranded because of the U.S. blockade.

A day late and a dollar short: Exporting Canadian natural gas to the EU

If the United States is to use any of this crude, as Trump says he will, the obvious first choice would be crude oil intended for Venezuela’s dark or shadow fleet. Given the bellicose nature of many members of Trump’s cabinet, crude oil shipped to Cuba could be next. Seizure of this crude could be used to offset some of Mexico’s ongoing export decline.

Chevron and several smaller companies could increase Venezuela’s production by half a million barrels a day over the next 18 months at a cost of $7 billion. Trump has said these costs could be reimbursed by the United States.

The options for Canada

If more Venezuelan crude oil flows into the United States, it could represent a serious threat to Canada, especially if it replaces supplies of Canadian heavy crude.

For example, in 2024, Texas and Oklahoma used almost 575,000 barrels a day of heavy crude oil, most of which was shipped from Alberta. This was worth $20 billion or almost 20 per cent of the total revenue generated from the sale of heavy crude that year.

Given the importance to Canada of the sale of crude oil to the United States, increasing flows of Venezuelan crude into the United States could have serious economic repercussions for Canadians.

Which, however coincidental, could be part of Trump’s plan to make Canada the 51st state.

The most sensible solution to the 51st state threat would appear to be expanding our limited pipeline network to the Pacific (through British Columbia) or building new pipelines to the Arctic or Atlantic (for example, through Churchill, Man., or Saint John, N.B.), or both, to let Canada’s crude oil reach new markets outside this hemisphere.

Assuming, of course, that the world’s most powerful navy won’t be deployed to all three Canadian coasts in a variation of the Venezuelan blockade.