Ottawa should reexamine the Oil Tanker Moratorium Act passed by the previous Trudeau government, in light of the new emphasis on nation-building projects as well as growing, effective Indigenous involvement and oversight. Times have changed and reconciliation must guide our path forward.

The law does not ban tankers outright. Instead, it regulates the loading and unloading of crude oil. The law bars tankers carrying more than 12,500 metric tons of crude from loading or unloading at ports and marine installations along British Columbia’s northern coast.

The problem with the tanker law and any similar law lies in rigid prohibition. The act forbids crude oil tankers over a certain tonnage regardless of safety measures or potential economic benefits. It contains no mechanism to consider alternative risk-mitigation measures or to permit future projects that might meet stringent environmental standards and secure Indigenous consent.

Ottawa should work with B.C., the Western provinces, industry and Indigenous groups to develop new policies for the area that would preserve strong environmental protection, while enabling responsible economic development and empowering coastal First Nations in decision-making.

Indigenous communities on B.C.’s northern coast have valid reasons to be cautious about tanker traffic near their territories. They deserve to weigh all impacts, positive and negative.

At the same time, other Indigenous communities in B.C. rely on some tanker traffic to move oil and natural gas exports to Asian and other markets.

For example, Haisla Nation, Wetʼsuwetʼen Nation, Haida Nation, Metlakatla First Nation (Tsimshian), and Nisga’a Nation have some limited marine tanker traffic. All, of course, are concerned about safety and the marine environment, although some expressed mixed support for “world-class” safety measures for tanker traffic rather than a full ban, arguing that with proper regulation, economic benefits can be balanced with environmental safeguards.

These interests need not be irreconcilable. One community’s economic self-determination should not automatically negate another’s.

Ottawa needs to admit where it’s wrong

Prime Minister Mark Carney is technically correct that there is no private company currently proposing an oil pipeline from Alberta to northern B.C. – a key demand on Ottawa by Alberta Premier Danielle Smith.

However, the federal government should acknowledge that its policies have created regulatory hurdles that discouraged investment in pipelines. If Ottawa wants to advance major oil and gas projects as part of its nationbuilding strategy, it must rethink its previous approach that deterred investors. One significant hurdle has been the tanker ban.

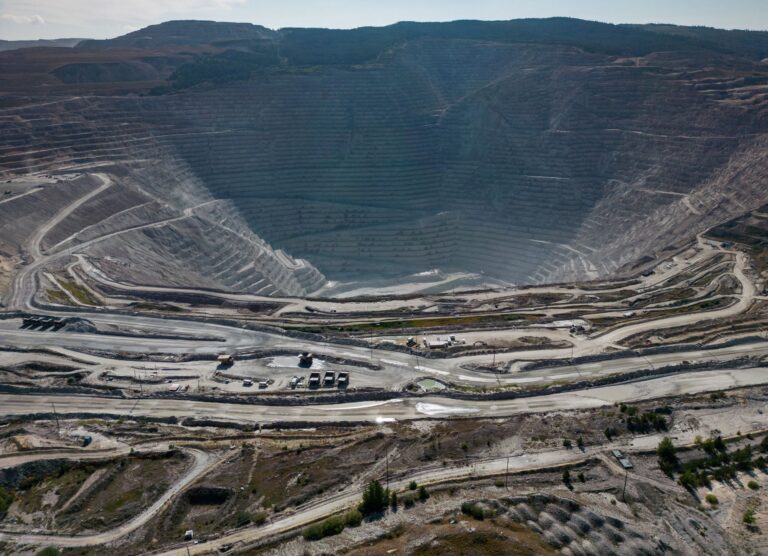

The current absolute ban constrains oil and gas projects, including Indigenous-led initiatives, such as the Northern Gateway project and the proposed Eagle Spirit pipeline.

It removed a direct marine export route that these projects planned to use to reach international markets. It also created regulatory and commercial uncertainty that complicated investment decisions and planning for pipeline proponents and potential buyers.

The status quo harms Indigenous communities that depend on marine traffic for project success. Deeper consultations before the ban was enacted would have shown that many Indigenous communities would suffer under such an extreme approach.

The federal government should not listen only to communities that support a ban. As well, Ottawa’s and B.C.’s commitments to the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) and the need for free, prior and informed consent require governments to consider the interests of all Indigenous communities when making such decisions.

Oil spills from modern tankers have become exceedingly rare thanks to double-hull designs and advances in navigation and vessel safety. Authorities recorded no tanker spills within the region covered by the bill even before the law existed. Alberta Senator Elaine McCoy noted after attending many committee sessions on the law is that B.C.’s coast has seen only three oil incidents since 2006 — none of which would have been prevented by the terms the law.

Good options exist for change

We should revisit the many constructive suggestions submitted to government for improving or redesigning this legislation. Policymakers could adopt compromise measures such as a phased or conditional tanker ban that allows limited, controlled access under strict safety and environmental standards. They could require enhanced safeguards, robust emergency response plans and effective monitoring before lifting or modifying restrictions.

Ottawa could keep a default ban but create a clear exemption process. For example, the federal government could establish environmental and safety standards that projects must meet to qualify for exemptions.

It could permit projects that meet or exceed stringent criteria — advanced vessel design, mandatory tug escorts through sensitive areas, real-time monitoring and mandatory early Indigenous involvement.

All affected communities should help develop those standards, incorporating coastal First Nations’ knowledge alongside scientific data.

Ottawa should also require Indigenous-led marine monitoring and response teams and establish stable, generous compensation funds to provide immediate disbursements to local First Nations in the event of incidents.

A clear, predictable regulatory framework co-developed with Indigenous communities would increase investor certainty and improve relations among the federal government, industry and Indigenous Peoples.

If Ottawa truly wants to advance oil and gas projects while respecting Indigenous self-determination, it must replace inflexibility with a more nuanced approach. We can better protect sensitive marine and coastal ecosystems, respect Indigenous rights and allow responsible marine-based economic opportunities. The first step is flexibility.