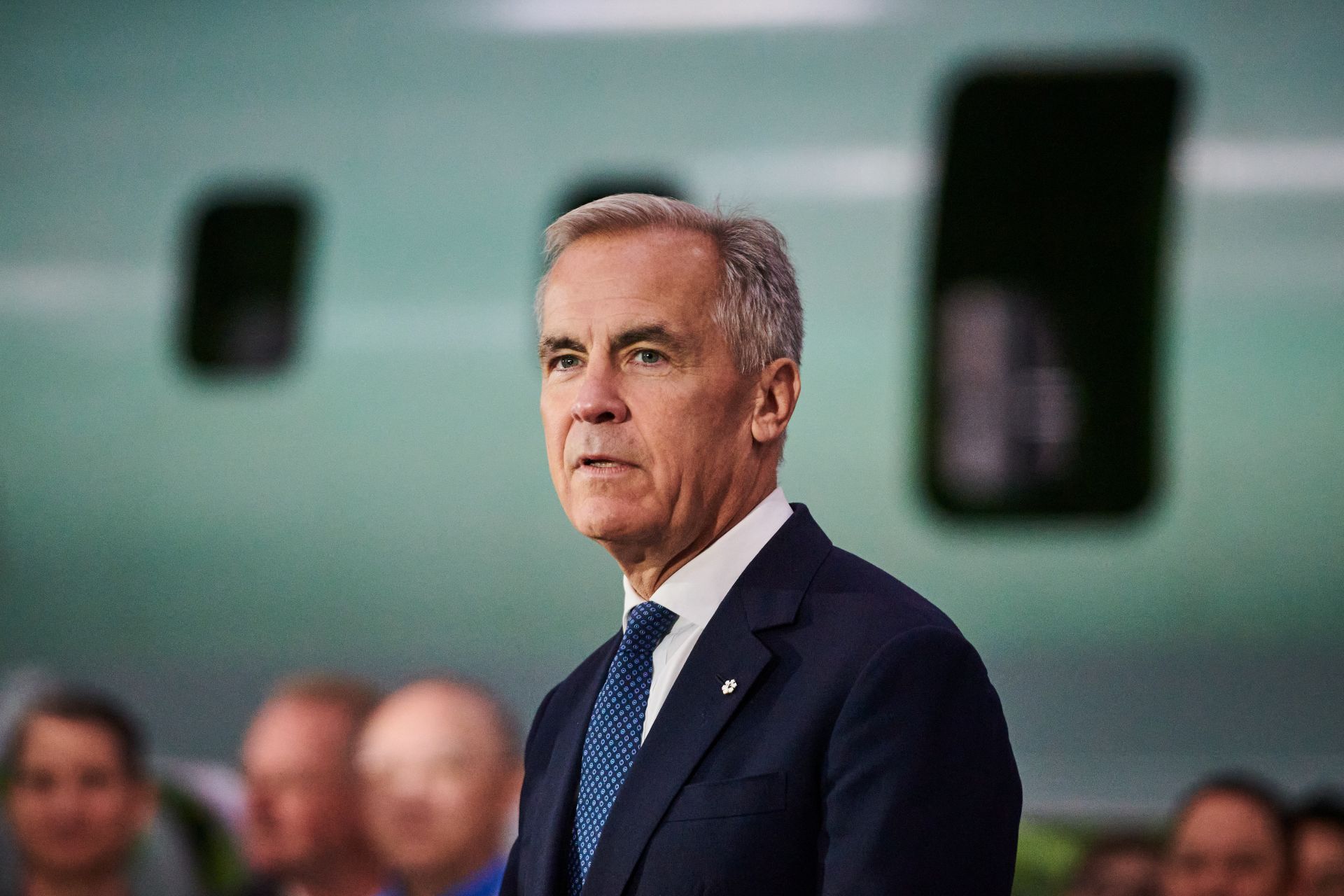

It’s notable that Prime Minister Mark Carney has continued the practice of public mandate letters. They have become a highly visible instrument of governance at the federal level, a dramatic departure for a form of communication once so private that it was the equivalent of a semi-secret handshake between the PM and his or her ministers.

It’s been 10 years since the switch flipped on mandate letters, when Justin Trudeau started making them public. Historically, they were scarcely different from medieval holy script, intended to be seen by only a select few.

In continuing the tradition of making them public, Carney has underscored their importance as an agenda-framing tool. But gone are the days of 800 commitments spread across the ministry for each set of mandate letters. So detailed and lengthy were Justin Trudeau’s letters that the overall effect was a tendency toward commitment sprawl.

Carney appears to have sacrificed this level of precision, drafting instead a single mission-driven mandate letter to all ministers and the secretaries of state. It’s a significant evolution in the use of mandate letters. Why do it? And will it be an improvement?

First on the federal scene

Canada’s first public mandate letters were released early in Trudeau’s first mandate. For the first time, commitments became known to and scrutinized by public servants across the government, as well as stakeholders and citizens.

From my perch in the Privy Council Office, I saw first-hand the priority given to these letters by political staff. All levels of the Prime Minister’s Office were engaged in the development and communication of commitments, and in the tracking of them over the length of a mandate.

In 2015, there were 35 letters, each with an English and French version, and Trudeau needed to be comfortable signing them. I took him through each one in a one-on-one briefing that lasted two hours.

I also supported the Carney government in the development of its mandate letter.

In the Trudeau government, the level of detail and number of commitments for each to-do list varied considerably, but every minister needed to have some explicit commitments if for no other reason than to justify their inclusion in the ministry.

Commitments sprawled amid a strong push for co-operation, which multiplied (and divided) responsibility for initiatives with horizontal aspects.

It is true that government can and must be capable of launching more than one initiative at a time. But this stretched credulity for some observers. These critics argued that a government with a dozen priorities, let alone 800, really has no priorities. The proliferation of commitments and the uneven progress in fulfilling them helped create an impression of a government that had trouble making choices and following through.

The central role the Liberal electoral platform played in catapulting the Trudeau government to victory, particularly in 2015, helps explain the prominence of the platform in 2015 and in subsequent letters.

Ministerial mandate letters: Another nail in the coffin of cabinet government

It also might explain why some initiatives were challenging to implement. In general, the farther behind a party is, the greater the pressure to identify an elusive winning set of issues.

In the pragmatic terms of a political partisan, the cost of making a promise that helps a party win is having to deal with the fallout of an ill-advised commitment while in office. The cost of never making promises for fear that they may not be good policy could be never winning office in the first place.

The former may be inconvenient, even awkward. The latter is more likely to be top of mind for an organization whose raison d’être is winning office.

The challenge of delivering on hundreds of commitments proved taxing for the Trudeau government. Criticism grew as high-profile commitments went unfilled. Boil-water advisories did not end for affected Indigenous communities. Nor did first-past-the-post elections.

Yet the Trudeau government adopted a similar letter template in December 2019 and December 2021.

Carney’s singular approach

The prime minister is departing from his predecessor’s tendency to directly transcribe platform commitments into government policy. The single mission-driven letter is a government-wide approach that places emphasis on the government’s overall direction.

By doing so, Carney is asking Canadians to place trust in the government’s direction as a whole rather than a suite of specific commitments. As part of mandate-letter follow-up, ministers have returned with their proposals for realizing the mission-driven themes.

The single letter appears to empower the public service to suggest the optimal approach for fulfilling the government’s seven missions rather than be relegated to the margins of the “how” of implementing specific election commitments, as was more likely to be the case during the Trudeau government.

From a public-interest perspective this additional flexibility is to be welcomed.

What accounts for this changed approach from many mandate letters to a single one and from hundreds of commitments to seven missions? Two explanations come readily to mind:

Political circumstances

The Liberal platform in the 2025 election was less central to the success of the Carney Liberals. Indeed, in some respects, appearing as it did after the final leaders’ debate and in the last week of the campaign after the start of advance polling, the Liberal platform very much appeared to be an electoral afterthought.

Instead, the Carney ballot-box question revolved around who was best suited to address the challenges and potential existential threat posed by the Trump administration. Given this, a direct transcribing of the platform was not seen as necessary to Carney’s implicit electoral bargain with Canadians.

Successor differentiation

The yin-yang of government succession may also have been at play. Each new government, whether of the same affiliation or not, seeks to differentiate itself from its predecessor, and not simply in policy terms but also in how it operates.

Thus, former prime minister Jean Chrétien’s managerial politics begat former prime minister Paul Martin’s “politics of ambition,” which begat Stephen Harper’s five priorities, which in their turn begat Trudeau’s “sunny ways” and focus on results and delivery and evidence-based policy, which begat Carney’s “focus, determination and fundamentally different approaches to governing.”

From this perspective, Carney’s seven-missions single mandate letter is a significant early example of differentiating himself from his predecessor.

An approach that suits

Carney has cemented into Canadian practice the core mandate-letter innovation of the Trudeau government.

His decision to adopt a more focused set of ambitious, broad objectives or missions provides an avenue for greater, more meaningful participation by his ministers and secretaries of state by including them in the development of specific mission initiatives.

On the whole, his approach seems better suited to the nature of the mandate he has earned. Whether the Carney mandate letter is ultimately seen as a successful innovation is likely to rest on the quality of the proposals coming from ministers and secretaries of state as well as subsequent implementation.