When ChatGPT exploded onto campuses in late 2022, universities scrambled. Some banned it, others experimented with it and many looked the other way.

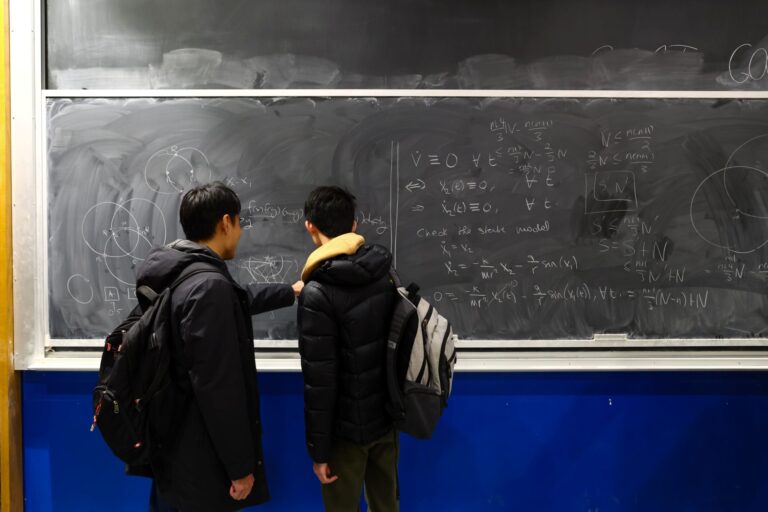

For students, the tool became as natural as Google or Grammarly. For faculty, it sparked deep unease. Would essays still matter? Could assignments still be trusted? What happens to academic integrity in a world where machines can write as well as humans?

Generative AI is no longer a curiosity. It is transforming higher education. Used well, it can personalize learning, make classrooms more accessible and reduce administrative burdens.

Used poorly, it can entrench inequality, fuel misinformation and undermine public trust in credentials.

Canada’s post-secondary institutions are at a crossroads.

Yet, there is no national framework today to guide universities and colleges in balancing these opportunities and risks. Without it, higher education institutions will continue to implement patchwork responses – some racing ahead, others banning tools outright and students being left to navigate inconsistent rules.

The federal government – in partnership with the provinces, which have constitutional responsibility for education, and with the post-secondary institutions themselves – should act on two fronts: establish the needed national regulatory framework and embed AI literacy across higher education.

Ottawa could begin by working with these partners to create a national advisory council on AI in education to provide interim guidance while longer-term standards are developed.

In addition, through existing federal-provincial co-ordination bodies such as the Council of Ministers of Education, it could set baseline principles and fund pilot programs, faculty training and student orientation modules to ensure national guidelines translate into consistent practice on campuses rather than remaining abstract policy.

The promise and the risks

Generative AI can do more than draft essays. It can act as a tutor, explaining complex concepts, generating practice problems and adapting learning materials to individual needs.

For students with disabilities, AI can provide real-time transcription, text-to-speech or translation support. It can fill gaps where traditional accommodations fall short. It has the potential to improve accessibility for the 20 per cent of undergraduate and 11 per cent of graduate students who are disabled.

International students benefit from AI translation tools that make course material more accessible in English and French.

Administrators are beginning to use AI for routine tasks such as sending deadline reminders or handling admission inquiries, freeing human staff to focus on higher-value work. Professors are experimenting with lesson planning and dynamic content creation.

Yet the risks are real. AI detection tools are notoriously unreliable, sometimes falsely accusing international and non-native English speakers of cheating. Large models often generate “hallucinations” – convincing but inaccurate information that can mislead students. In addition, these tools can reinforce racial and gender bias because most of them are trained on Western-centric data.

Access is also uneven because some students cannot afford paid AI subscriptions or lack reliable internet. Indigenous students report significantly lower familiarity with AI tools compared to other groups, reflecting broader digital divides.

A fragmented landscape

Today, only about half of Canadian universities have any formal policy on generative AI and most of them leave decisions about its use to individual instructors. The result is confusion, inconsistency and inequity.

Meanwhile, other countries are moving ahead. The U.K.’s Russell Group of leading universities, for example, has developed principles to guide responsible AI use, including safeguards for student data and fairness in assessment. Canada needs something similar tailored to our unique education system and cultural context.

We have already invested billions in AI research and infrastructure, from the pan-Canadian AI strategy to the newly created Safe and Secure Artificial Intelligence Advisory Group. While important, they remain largely disconnected from higher education policy.

What Canada should do

First, establish a national regulatory framework. A clear set of standards would help universities, colleges and students navigate this new terrain. This framework should:

- define acceptable uses of generative AI in teaching, learning and research;

- require compliance with data protection laws to safeguard student information;

- be developed in consultation with experts from Indigenous and other underrepresented groups to ensure cultural sensitivity;

- promote human oversight to preserve integrity and accountability.

Without national co-ordination, the current patchwork of policies will only deepen inequalities.

Second, embed AI literacy across higher education. Every student – whether in engineering, business, social sciences or the arts – should graduate with a foundational understanding of how these tools work, their benefits and their risks.

This requires federal funding through the provinces for curriculum development in English and French; training programs for faculty on ethical and pedagogical use of AI; the appointment of chief AI officers at post-secondary institutions to lead strategy and compliance; and targeted support for rural, remote and Indigenous communities to bridge digital divides.

If we move quickly, we can shape not just how AI is used in education, but how it is understood by the next generation of Canadians.

A dual path forward

The choice is not between regulation or education. It must be both. A national framework will ensure fairness and accountability. Widespread AI literacy will ensure students and faculty use these tools responsibly. Together, these approaches can help Canada harness the benefits of generative AI while safeguarding the integrity of higher education.

Generative AI is as transformative today as the internet was a generation ago. The question is whether Canada will approach it with vision and co-ordination. We should seize this moment to build a proactive, inclusive strategy that prepares our education system for the AI era.