The Trudeau government’s lofty ambitions of fighting climate change are unlikely to succumb to Donald Trump’s presidency with a bang, but they could go out with a whimper. In this article, based on oil industry documents obtained by Greenpeace Canada under freedom of information legislation, I explore how the industry’s lobbyists are attempting to weaken the implementation of federal climate policies to bring them in line with the Trump administration’s views, in practice if not explicitly.

There is no doubt that Trump’s inauguration as the 45th president of the United States signals a rollback on climate change action south of the border. On the campaign trail, Trump’s energy policy consisted of boilerplate industry talking points cloaked in populist rhetoric. His transition team is dominated by climate change deniers, and he chose a former CEO of ExxonMobil to be secretary of state.

Trudeau has made action on climate change one of his signature issues, so he’s not likely to change his public position. Indeed, when pressed on whether Canada’s climate plan could put us at a competitive disadvantage, Trudeau countered that “if the United States wants to take a step back from [action on climate change], quite frankly, I think we should look at that as an extraordinary opportunity for Canada and for Canadians.”

Yet the advent of a Trump administration has created an opening for oil industry lobbyists to suggest that Canada will be less competitive if we take action to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and the United States does not. This concern will no doubt be a major consideration as the federal and provincial governments work out the details of the Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change. The framework, announced in December 2016 after a year of negotiations, contains a number of proposed measures but few details on how the measures will be turned into regulations.

The oil lobby’s argument on competitiveness successfully stymied the Harper government’s attempt to limit GHG emissions from the oil sands in 2013 (when oil was at $100 a barrel), so it is worth examining how the same players could water down the effectiveness of the current federal government’s proposed policies, even though Trudeau would not publicly repudiate them.

(The two Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers [CAPP] documents obtained by Greenpeace Canada under Saskatchewan’s Freedom of Information Act are available online. In this article, “slides” are from CAPP’s September 2016 presentation on proposed methane regulations; “pages” are from CAPP’s August 2016 submission to the federal climate policy consultation.)

These are the federal government’s three biggest climate policy commitments, as measured in anticipated megatonnes (Mt) of reductions in GHGs:

- The regulations to reduce methane emissions from the oil and gas sector (20 Mt). The oil lobby is exaggerating the costs of compliance in order to delay implementation and reduce the scope of mandatory (regulated) requirements.

- The national price on carbon (estimated at 18 Mt). The oil lobby is advocating for carbon pricing to be revenue-neutral for its sector, which would reduce the pressure for structural change to a low-carbon economy wherein fossil fuels are replaced by renewable energy sources.

- The clean fuel standard (30 Mt). This is still largely undefined, but the oil sands lobby won an early victory by ensuring that the standard won’t distinguish between the carbon intensity of various crude oil feedstocks.

Methane regulations

Tackling methane — a particularly potent GHG — is one of the quickest and cheapest ways to achieve large reductions in emissions. This is why Canada and the United States agreed in March 2016 to reduce methane emissions from the primary source: the upstream oil and gas industry (exploration and production). Its methane releases, including both leaks and intentional emissions, total 45 Mt of carbon dioxide equivalent per year, which is comparable to the total emissions from Atlantic Canada.

Environment Canada and the US Environmental Protection Agency are developing regulations to require a 40 to 45 percent reduction in these emissions relative to 2012 levels by 2025. The US commitment to this measure under a Trump administration is now in question.

The Canadian government had discussions with the oil industry from May to September 2016 about draft methane regulations, which will probably be released this month, with the final regulations to be published by the end of 2017. In its September 2016 presentation, CAPP highlighted that “Canadian production is already at a risk of being displaced by U.S. competition” and declared that it was “not a good time to impose additional costs on industry” (slide 21); all further references to slides are to this presentation).

CAPP then laid out its alternatives to Environment Canada’s proposed regulations. CAPP’s proposals would do the following:

- Lead to higher emissions: According to CAPP’s own estimates, its proposal would result in only a 20 Mt reduction, whereas the federal proposal would achieve 23.1 Mt in reductions (slide 37). To put this in perspective, the federal government’s coal phase-out will achieve 5 Mt of incremental reductions. CAPP says that its members can still meet the federal reduction target because it is assuming that the regulations will be more effective at reducing emissions than Environment Canada expects.

- Require less frequent inspections: Leak detection and repair is a highly effective way to reduce emissions. CAPP proposes that inspections be undertaken only once a year, while acknowledging that this would achieve only 70 percent of the leak reductions brought about by more frequent inspections (slide 55).

- Take longer to achieve reductions: The longer it takes to implement these measures, the higher the total of GHGs emitted. Yet CAPP argues for “delaying the timing of regulatory implementation for existing equipment beyond the currently proposed 2020” (slide 42) and states in its August 2016 submission to the federal climate policy consultation, “We believe that mandatory retrofitting of all equipment would not be cost effective in meeting emissions targets. Companies should be given discretion over determining which equipment to retrofit and when to meet targets” (page 8).

- Make some parts voluntary, as opposed to legislated: CAPP supports regulated standards for new equipment based on “economically-achievable thresholds” (slide 40) but proposes that “progress for existing equipment is best achieved by non-legislative industry/government/ENGO [environmental nongovernmental organization] partnerships” (page 8). If these reductions would be undertaken voluntarily, however, we have to ask why they aren’t being done now.

- Overestimate costs: There is a long history of industry and, to a lesser extent, regulators overestimating the costs of environmental regulations. In the case of industry, it is likely at least in part a negotiating strategy. CAPP says that the cost to industry of implementing the federal methane regulations would be roughly triple what Environment Canada calculates: $4.1 billion over eight years, compared with Environment Canada’s estimate of $1.3 billion (slide 37).

Industry push-back on environmental regulations is to be expected and is most effective when conducted behind closed doors. What is somewhat novel, however, is that CAPP links its support for methane regulations (in a weaker form) to a shift in the approach that “enables funding for clean technology and innovation development and deployment” (slide 40), a position elaborated in its lobbying on carbon pricing.

National price on carbon

The Liberal government’s first big climate policy move was to announce that provinces have until 2018 to adopt a carbon pricing scheme, or the federal government will step in and impose a price for them. The biggest provinces — Ontario, Quebec, British Columbia and Alberta — were already implementing some form of carbon pricing, and between them they generate 80 percent of Canada’s GHG emissions. Nevertheless, the federal announcement in October 2016 was an important step toward creating greater consistency across the country.

The oil industry formally supports action on climate change (in exchange for pipeline approvals) but wants to shape how the policy is implemented so as to minimize the impact on its own operations. As CAPP says on its website, climate policy “should maintain competitiveness of Canadian industry, ensure compatibility with major trading and economic partners (particularly with the U.S., our largest trading partner), and compliance should be achievable within the context of growing production.”

One of the ways CAPP seeks to achieve these goals is by advocating that carbon pricing be revenue-neutral for its industry. In CAPP’s August 2016 submission, the group asks that all the revenue collected from the upstream oil and gas sector (which CAPP acknowledges is the largest source of GHG emissions in the country) be returned to those same companies: “One of the decisions governments need to make is what to do with the revenue generated from the carbon pricing mechanism. There are many options available to enable innovation for distribution of this generated revenue; CAPP recommends that to enable innovation, revenue generated by industrial emitters is best recycled back to the industry for technology and innovation” (page 13).

This recommendation would dramatically weaken the effectiveness of the federal policy. The primary advantage of a carbon price is that it sends an economy-wide signal to investors and consumers, leading to a shift to lower-carbon options. If the largest share of the revenue goes back to the oil industry, the signal to investors to switch to low-carbon energy is muted.

CAPP’s position bodes ill for the long-term transformation of the economy. As part of the Paris Agreement, Canada committed to achieving net-zero emissions by the second half of the century. More recently, the Trudeau government’s long-term decarbonization strategy committed to at least an 80 percent reduction of GHGs by 2050. Meeting this target requires a transition off oil, which is at odds with CAPP’s advocacy of a form of carbon pricing that would “continue to promote investment, jobs, oil and natural gas sector growth” (page 18).

Clean fuel standard

In November 2016, the federal government announced that “it will consult with provinces and territories, Indigenous peoples, industries, and non-governmental organizations to develop a clean fuel standard.” Details won’t be known until the federal government releases a discussion paper, expected this month, but there were two significant bits of information in the announcement.

First, the standard is expected to achieve a 30 Mt reduction, making it the single largest source of new GHG reductions in the Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change. This is a surprisingly high figure, given that the federal-provincial working group on the framework estimated that a low-carbon fuel standard could achieve a reduction of 11 to 22 Mt. The low-carbon fuel standard would have targeted only liquid fuels (gasoline, diesel and heavy fuel oil), so the difference could be in the extension of the clean fuel standard to include gaseous (natural gas and propane) and solid fuels (petroleum coke) — but 30 Mt is still a very big number.

Low carbon fuel standards typically require a reduction over time in the average carbon intensity of fuels. This can be achieved by switching to sources that have lower life-cycle emissions (which puts oil sands crude at a disadvantage because of the extra energy and hence emissions required to extract and process bitumen); adding biofuels to conventional fuels (e.g. adding ethanol to gasoline); and/or switching fuels (e.g. from gasoline to electricity, in the case of electric vehicles).

The other significant element in the announcement was that the standard “would not differentiate between crude-oil types produced in or imported into Canada.” This is a big win for the oil industry, as it means that high-carbon oil from the oil sands won’t be disadvantaged relative to crudes with lower life-cycle emissions. The oil industry worked very closely with the Harper government to defeat the provision in the European Union’s fuel quality directive that would have differentiated between crudes based on life-cycle emissions. CAPP has also opposed the California Low Carbon Fuel Standard, which it says discriminates against oil sands crude.

If the new standard won’t differentiate between crudes, then the key question is what will be used to replace fossil fuels: biofuels or electricity. The oil industry is generally more supportive of biofuels — like ethanol or biodiesel that can be added to oil, or biogas that can be added to natural gas — because biofuels use, and thus reinforce, the existing oil-and-gas-based energy infrastructure such as pipelines, furnaces and internal combustion engines. Biofuels also have significant GHG emissions from growing and harvesting the crops, whereas electricity can be very low-carbon if it is generated from renewable options such as wind or solar power.

Yet Canada’s official Mid-Century Long-Term Low-Greenhouse Gas Development Strategy argues that electrification is key to the deep decarbonization of the economy required to achieve the Paris Agreement’s goal of limiting warming to below 2 degrees Celsius. Electrification requires new infrastructure (such as electric vehicle charging stations) to challenge the energy status quo. That, in turn, will require governments to invest in public infrastructure — which will be less likely to happen if the bulk of the revenue from carbon pricing is being handed back to oil and gas companies.

The real threat that the election of Donald Trump poses to Canadian climate policy is not that Canada will suddenly turn its back on the Paris Agreement, but that his victory empowers the oil lobby to win the backroom battles over implementation. Taking these discussions out of the backrooms and into the public sphere is an important step toward ensuring that climate policy is made in the public interest.

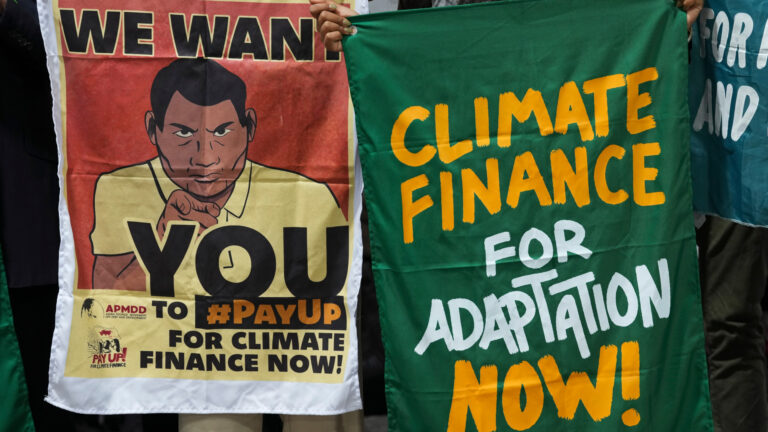

Photo: A young protester during a protest in front of Trump Tower on November 19, 2016 in Toronto, Canada. / Shutterstock.com

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.