This article was adapted from Whipped: Party Discipline in Canada (UBC Press, 2020).

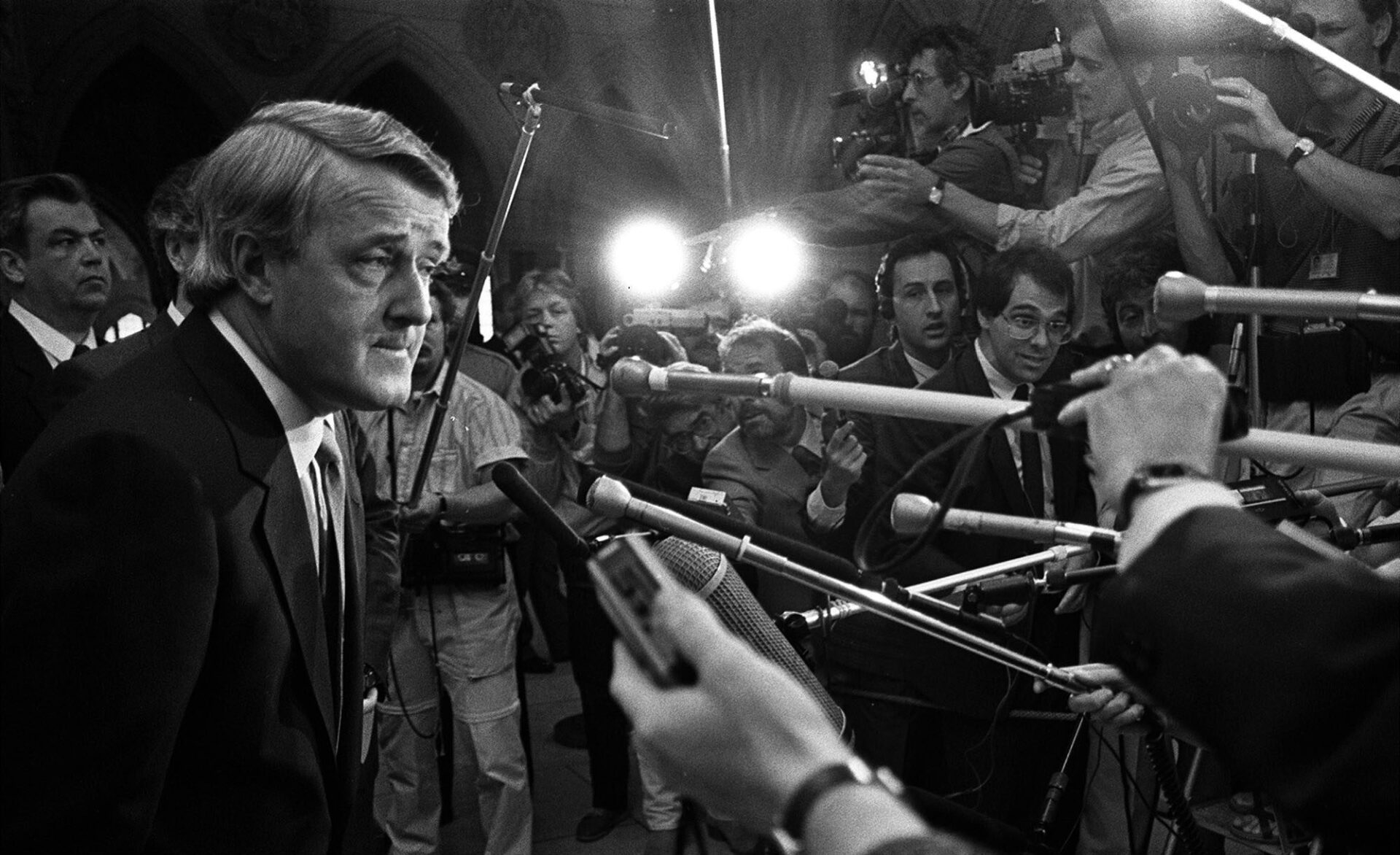

One of the most unusual and admirable qualities of Brian Mulroney, who died February 29, was how tirelessly he worked to connect with people on a personal level, particularly members of the Progressive Conservative team.

Most prime ministers, including Justin Trudeau, have little time to talk with MPs outside of national caucus meetings. In contrast, Mulroney made it a priority to regularly check in not only with hundreds of his Progressive Conservative Party’s MPs and senators, but also with members of its electoral district association in ridings throughout Canada. He even reached out to parliamentarians’ family members. This personal rapport was a huge reason why so many PCs were unwavering in their loyalty to him during his most ambitious political initiatives and in his darkest political moments.

His exceptional hold on caucus support was because of an unwavering commitment to personal outreach. Upon becoming the Progressive Conservative leader, Mulroney was determined not to allow a repeat of previous party infighting. “In the parliamentary system, caucus is the most important piece of the puzzle,” Mulroney said in an interview in 2018. “If you are the leader of a party in Parliament, you had better make it your business to ensure that your caucus is behind you all the time. That can be brought about only by personal commitment and personal action.”

In 1992, the PC government was nearing the end of its tumultuous second term in office marked by a number of polarizing policy initiatives. The caucus was encouraged to think like trustees who prioritize the national interest while the media gorged on public angst and the whiff of scandal: Six PC MPs had defected to form the Bloc Québécois; two former PC MPs were now Independents; another had been sentenced for corruption; byelection losses were mounting; and the Reform Party was siphoning support in the West.

A majority of Canadians wanted the prime minister to resign and in one political poll, just 11 per cent of respondents preferred the PC Party. With political jobs on the line, public sniping and efforts to install a new leader would be a normal course of events. Yet most Tories were steadfast in their allegiance to their leader and party. Mulroney’s exceptional efforts to form personal relationships and build trust through inclusion had fostered that loyalty. Caucus members were made to feel that they mattered. The size of the cabinet grew to include more of them. Backbenchers contributed through caucus committees and task forces. The prime minister wrote letters to all members of the caucus, inviting their input on priority items for the party’s election platform.

In his own words: Brian Mulroney’s writing in Policy Options

From the archives: Kim Richard Nossal on Brian Mulroney’s legacy

Mulroney believed caucus members must see results when they brought him concerns. Four to five caucus relations staff in the PMO worked with the governing party MPs to resolve issues. They offered the assistance of the prime minister when warranted and made MPs believe that the PMO was looking out for their interests. The quid pro quo was a heightened expectation of compliance when staff informed backbenchers that the boss wanted them to do something. Political staff embodied the prime minister’s belief, which he relayed in an interview, that “caucus solidarity is indispensable for long-term success,” and requires a party leader who “works at it relentlessly.”

On Wednesdays when caucus met, a handful of MPs attended a breakfast meeting at 24 Sussex Drive, the prime minister’s official residence. Mulroney took notes while listening to a rotation of three to five of his party’s backbenchers from different parts of Canada who might have been steered to a seat next to a caucus adversary. Then, around 9 a.m., he met in his parliamentary office with the PMO chief of staff (who oversees political staff) and the clerk of the Privy Council (who oversees public servants).

Mulroney raised the problems voiced over breakfast and directed that the MPs’ concerns be addressed, especially if something involved a localized campaign promise. His determination to inspire commitment was on full display in caucus meetings, largely celebratory events from which PMO staff were excluded. Afterward, he would meet again with the chief of staff and the clerk and once again relayed concerns from backbenchers. If a PC backbencher complained about an inaccessible minister, the prime minister arranged for the minister to receive a message that others were interested in their cabinet position.

After question period at 3 p.m., backbenchers brought people from their electoral districts to meet the prime minister for a short chat and a photograph. On Wednesday evenings, Mulroney placed approximately 10 telephone calls across the country to praise his caucus members.

The president of a PC electoral district association would field a phone call from the prime minister about how the area’s MP had spoken forcefully in the caucus that morning. If the MP’s concern was about the need for a new bridge, the prime minister instructed PMO staff to get the minister of public works to travel to the riding with the member to look into getting the bridge built. Mulroney encouraged the electoral district president to share this information with others. He bolstered the remarks by telling journalists about a member’s passionate advocacy for local issues.

Mulroney spent years making sure that he knew all of the caucus members, including their families. He connected through flattery and by acknowledging that backbenchers’ spouses make sacrifices. He wrote letters to compliment MPs on their speeches in Parliament and their policy presentations. The caucus relations staff kept their boss abreast of who was off sick, who was celebrating a birth or anniversary, who had marital problems, whose mother was in hospital, and who was mourning a death.

Mulroney – described as a “phoneaholic” – telephoned MPs and their relatives to recognize accomplishments or to express concern if someone was experiencing illness, loss, or tragedy. Former PC MP Garth Turner recounted that “Mulroney would call out of the blue, full of effusive praise and leaving his subject – friend and foe alike – swimming in endorphins.”

At cabinet meetings, the prime minister updated his ministers about MPs who were celebrating a milestone or going through hardship. Mulroney’s former chief of staff Hugh Segal recalled in his book The Long Road Back that the prime minister once became angry over not being told that a PC MP’s wife had broken her arm in a car accident. The lesson for the entire PMO was that “without caucus cohesion, unity, and loyalty, nothing else mattered.” Mulroney also phoned junior political staffers and local party supporters. Surprised staff received flowers to mark special life events. He sent congratulatory notes to MPs’ children graduating from high school.

Caucus meetings like no others

Mulroney made it clear to PMO schedulers that caucus meetings were a priority unless an international leaders’ summit required him to be out of the country. Meetings began with a standing ovation from backbenchers and senators when he entered the room. He listened attentively for up to two hours and took notes. No staff were present, which enabled free-flowing conversation. Parliamentarians were encouraged to be critical, but anyone brave enough to criticize the prime minister might be cut off by a backbencher who rose to the leader’s defence.

To conclude the meeting, Mulroney would deliver a passionate motivational speech for up to an hour to drum up enthusiasm for the government’s agenda and to nurture feelings of a political family. The talks were entertaining barnburners as he switched between English and French. He told stories about the interesting people he had met on his travels over the past week, taking care to weave in the names of caucus members. The light fare warmed up the audience for serious comments about public policy and plans to persuade the electorate.

Progressive Conservatives were made to feel that they were revolutionaries who were part of something special that would improve Canada. Big-ticket items, they were told, might be unpopular but historic. They should anticipate polling numbers to dip when a government did something bold because citizens are generally averse to change. They were encouraged to look past short-term negativity and toward future laudatory headlines.

Mulroney relayed in his memoirs how he implored his caucus to be “key salespersons” and instructed them that they “must have the same message, the same themes, the same defence. There can be no divergent views.” He warned that opponents had designs on becoming ministers, that MPs had no friends beyond the caucus room, and that the media would not help them. He exhorted the caucus: “Don’t do it if you don’t want to read about it in the Globe and Mail the next day.” Those fearful about not being re-elected got an earful about the shallowness of their opponents. “If you don’t like the numbers, you can get the hell out,” Mulroney challenged naysayers, according to his memoirs. Backbenchers were reassured he would look out for them. He, in turn, expected them to support ministers who spoke on the prime minister’s behalf.

Mulroney took great pains to maintain morale when the government backtracked on a policy. He spent hours preparing caucus remarks to explain one such decision. Blaming adversaries, accepting personal responsibility, offering assurances that a media storm would die down and reinforcing the important role of an MP all featured in his summation.

No matter how low the party was in public opinion polls, or how anxious ministers and backbenchers were about the latest controversy dominating the news, Mulroney soon had them cheering and laughing. They exited the meetings feeling reassured, encouraged, flattered, entertained – and above all reminded that caucus unity is essential. “We were at 22 per cent in the polls and Mulroney was in full oratorical flight,” reminisced former MP Jim Edwards. “When the caucus meeting was over, if he’d called an election that day, we’d have cheered him for doing it! He was such a terrific motivator. He was absolutely genuine in caucus.”