Brian Mulroney’s tenure as prime minister from 1984 to 1993 demonstrates the appropriateness of the hoary Chinese curse “May you live in interesting times.” For Mulroney was prime minister at a time of a radical transformation in politics, in Canada, in North America, and globally, even though those changes were not always evident in September 1984 when Mulroney led the Progressive Conservative party to victory, with a massive majority in the House of Commons.

When Mulroney came to power, the Cold War was at its coldest. The shooting down of Korean Air Lines 007 by the Soviet air force in September 1983 had brought relations between the United States and the Soviet Union to a new low, with President Ronald Reagan characterizing the Soviet Union as an “evil empire.” The decision by the Reagan administration to provide sophisticated military aid to the mujahedeen in Afghanistan fighting the Soviet occupation force would turn the tide of a war that was already not going well for the Soviet Union. And the publicly stated determination of President Reagan to find a way to put in place a shield against nuclear attack threatened to undermine the very foundation of the balance of terror between the United States and the Soviet Union.

Over the four years before Mulroney came to power, relations between President Reagan and Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau had increasingly soured, not least because of Trudeau’s concerns about what he termed the “parlous” relationship between the superpowers. Trudeau’s vision of world politics differed dramatically from Reagan’s, and Trudeau was not hesitant to press those differences. The result was a friction in the personal relationship between the two leaders that exacerbated some of the more material conflicts between Canada and the United States in the early 1980s. Indeed, trade relations between Canada and the United States had deteriorated as protectionist sentiment in Congress deepened with the onset of recession. Attempts by both governments to duplicate the success of the sectoral free trade arrangements in autos and auto parts and in defence procurement had failed to achieve any substantial progress, instead revealing the depth of protectionism on both sides of the border. Given the generally poor state of Canadian-American relations, it was little surprise that one of the widely promised planks in Mulroney’s election platform in 1984 was his promise to “refurbish” the Canadian-American relationship.

Domestically, Canada in 1984 was marked by political and economic discontents. The deep fractures left by Trudeau’s patriation of the constitution and the refusal of the Québec government to attach itself to the new constitutional arrangements were continuing concerns. Moreover, the country’s financial situation was grim: the recession of the early 1980s produced large-scale unemployment, particularly in central Canada; after 16 years of deficit spending by the federal government, the deficit was continuing to spiral upwards.

And in 1984, the political party system in Canada looked as it had for many generations: two national parties, both of which had difficulty in transforming national support into seats, thanks to the first-past-the-post electoral system. Under Mulroney’s leadership, seized from Joe Clark in 1983, the Progressive Conservative party grew to embrace a wide variety of interests from across Canada, particularly in Quebec, enabling Mulroney to repeat the achievement of the Conservatives under John Diefenbaker in 1958 and sweep into power with an unprecedented majority of 211 seats in the House of Commons.

By the time Mulroney left office in 1993, this canvas looked radically different. At the global level, the Cold War was over, the Soviet Union having ceased to exist at the end of 1991 and Washington and Moscow having agreed to reprogram their nuclear arsenals. Across the globe, the end of superpower confrontation had brought political change as the calculus that had prompted great-power support of despotic, corrupt or authoritarian regimes changed and those regimes collapsed. On occasion, the collapse prompted particularly vicious civil wars, but this too ushered in another change: the willingness of the international community to intervene in a number of civil conflicts.

The management of an increasingly globalized economy had also changed during this period. The Uruguay Round of multilateral trade negotiations, launched shortly after Mulroney came to power, was in the final stages, and the World Trade Organization would be in place a little more than a year after Mulroney’s departure as prime minister. Moreover, with the end of the Cold War, multilateralism enjoyed a rebirth as “global governance” began to make its appearance in political discourse.

In North America, the Canadian-American relationship was in the process of being transformed by two trade agreements negotiated during Mulroney’s tenure. While the effects of both the Canada-US Free Trade agreement that came into force in January 1989 and the North American Free Trade Agreement that came into force in 1994 would not be fully evident until the mid-1990s, and while these agreements did not bring American protectionist impulses to an end, there can be little doubt that the achievement of a comprehensive trade agreement with the United States brought huge changes. While some Canadians suffered as a result of the unemployment and dislocation that occurred as firms rationalized their operations, in the aggregate Canadians would be much better off as a consequence of the massive increases in trade.

By the end of the Mulroney mandate, Canada would also have a goods and services tax, a highly visible tax of 7 percent introduced to replace the completely invisible manufacturer’s sales tax of 13.5 percent. But the Mulroney Conservatives proved no more capable than the Trudeau Liberals at grappling with government expenditures: by 1993, there had been no serious assault on the budget deficit, even though Ottawa was by then in an operating surplus — taking in more in taxes than it spent on programs.

By 1993, Canada’s political landscape would be unrecognizable as a result of the disintegration of the Progressive Conservative party over the course of the Mulroney mandate. Two new political parties, each with a regional base — the Reform party in the West and the Bloc Québécois — were formed during this period. Their appeal to voters would lead to the decimation of the PC party and the entrenchment of the Liberals in power after Mulroney’s departure. By 1993, national unity continued to be a problem, with Mulroney’s efforts to resolve the national unity dossier having been firmly rejected, first with the death of the Meech Lake accord in 1990, and then by the voters across Canada in the referendum on the Charlottetown Accord — both of which set the stage for the 1995 Québec referendum.

And Mulroney himself would leave politics widely disliked by the Canadian public; journalists would write unflattering accounts of his tenure as prime minister; and he would be hounded by an allegation of corruption and scandal in a notorious case that was not finally closed until 2003 with no proof of the original allegation having been presented, six years after the government settled his libel lawsuit on the courthouse steps, with an apology to the former PM and his family as well as payment of his entire costs.

Given the scope and rate of political change during Mulroney’s prime ministership, it is perhaps inevitable that his record could be judged as mixed. Moreover, appreciations of his tenure are made more difficult because of his personal unpopularity; because he has yet to write his memoirs; and because, unlike Trudeau, Mulroney does not have champions in the scribbling classes writing on his years in power, spinning the story of his time in power in particularly favourable ways. On the contrary, books on the Mulroney government’s corruption become best-sellers, while in-depth investigations into the charges of corruption levelled against Mulroney himself are not widely read.

As a result, appreciations of the Mulroney era are themselves mixed, with the consequence that some aspects of his record are, it can be argued, appropriately appreciated, while some others are overappreciated and some are underappreciated.

One of the most important changes in Canadian politics that will be associated with the Mulroney era is the transformation of the political landscape. Mulroney had been very successful in forging a winning coalition in 1984. But it proved impossible to sustain. Part of the problem was the fundamental contradiction deeply rooted within the PC party. Like many a shaky marriage, the union between the “Blue Tories” those with an ideological outlook more comparable to the right wing of the Republican party in the United States and the Red Tories” those who had a more traditional tory ideology — worked well enough as long as no one actually talked about the marital problems. Differences could be — and were — papered over, not mentioned, left to be resolved at a later time.

As a strategy for opposition, this might have been appropriate and politically effective. However, the process of governing exposed all the contradictions inherent in the union of these disparate ideological groups. And although Mulroney is frequently portrayed by critics as a leader in the mould of Margaret Thatcher or Ronald Reagan, in fact he shared little of the willingness of those leaders to engage in the kind of harsh politics with which the neoliberal is normally associated. The reality was that Mulroney, while himself no Red Tory, was unwilling to risk the coalition he had so carefully put together.

The irony is that that very desire to please caused major disaffection, with the result that the Reform party, founded in 1987 as a protest against the putative failure of the Mulroney Conservatives to protect Western interests, ended up putting at least half of the nails in the Conservative party coffin. And the other nails were provided by the collapse of the Québec part of the winning coalition of 1984 with the failure of the Meech Lake Accord and the decision of Lucien Bouchard to leave the Conservatives to form the Bloc Québécois.

In short, it is clear that the collapse of the historical, two-dominant-party model of Canadian politics will be one of the enduring legacies of Mulroney’s tenure as prime minister. But to what extent can the rise of these parties of protest that ended up balkanizing Canadian politics in the 1990s and beyond be attributed to Mulroney himself? Here the answer is less clear. On the one hand, there can be little doubt that many of the decisions of the Mulroney government fuelled Western alienation — the decision to award the CF-18 maintenance contract to Québec rather than Manitoba, for example. And there can be little doubt that the dominance of the Red Tory mix in the Mulroney cabinet did not sit well with large numbers of Western backbench MPs. On the other hand, there was a certain inevitability to the rise of a Western protest party: had the Mulroney Conservatives embraced the agenda that would have soothed Western concerns, PC support in central Canada would surely have been jeopardized.

Likewise, the collapse of the coalition with nationalists in Québec that had enabled the PC party to break the Liberal lock on that province was well beyond Mulroney’s capacity to prevent, even if he had used a less cynical phrase than ‘roll the dice” to describe the process of constitutional amendment. The sustained assault on the Meech Lake Accord mounted by prominent Liberals from January to June in 1990 was one of the key reasons why the Constitution Amendment 1987 died on June 23, 1990. And, ironically, by the time that the Charlottetown Accord was proposed with the agreement of all the major political actors, the die of regional protest had been cast, with a significant majority of ordinary Canadian voters in all regions rejecting the recommendations of their elites on the constitutional dossier. And in this mix, we cannot ignore the impact of the personal political ambitions of Lucien Bouchard, whose departure from the Conservative Cabinet assisted in the eventual collapse of the PC party’s national support in 1993.

There is, however, one change that Mulroney could have introduced, and which would have had an enduring effect on the Canadian political system. The huge size of the Conservative parliamentary majority in 1984 would have allowed Mulroney to introduce legislation altering the electoral system that had kept the Conservatives from power for much of the twentieth century. But changing the electoral system was never on the political radar screen in these nine years; instead, the dominant assumption was that since the new prime minister’s political skills appeared to have broken the Liberal lock on Québec — twice, no less — further action on the plurality system was not necessary. Ironically, one of the most negative legacies of the Mulroney mandate was that the Conservatives had the opportunity to change Canada’s hugely unrepresentative electoral system — and chose not to take advantage of the opportunity offered by this historic correlation of forces.

From the July 2003 archives of Policy Options: Ranking prime ministers of the past 50 years

The print version of Kim Richard Nossal’s article in Policy Options

By contrast, one of Mulroney’s enduring positive legacies will be the free trade agreements with Canada’s North American trading partners that were negotiated during his mandate, despite the fact that he had spoken out against free trade in 1983 and 1984. But there can be no doubt that free trade — even if it did not achieve Mulroney’s stated goal of guaranteed access to the United States market — had a transformative impact on Canada and the wealth of Canadians (even if it was not until the mid-1990s that those effects began to be revealed).

But while the Free Trade Agreement will always be associated with Mulroney, it could be argued that this is a somewhat overappreciated aspect of his record, in the sense that given the broader structural conditions it is likely that a comprehensive free trade agreement with the United States would have been sought regardless who was in power after 1984 — at least eventually. In other words, it is likely that had John Turner and the Liberals won the 1984 election, the Royal Commission on the Economic Union and Development Prospects for Canada under Donald Macdonald would still have recommended taking the “leap of faith”; the logic of growing American protectionism would still have suggested a comprehensive free trade agreement.

The difference, it can be argued, was in the timing. Given the number of members of the Liberal caucus who were then (and remain today) either deeply sceptical about, or outright opposed to, Canadian integration with the United States, it would have taken much longer for the Liberal party to have the internal debate on continentalization and the US that it eventually had in the early 1990s when they were in opposition. Where it can be argued that Mulroney made a difference was in the speed with which he made up his mind to change his mind, and the leadership he showed in making free trade a reality.

By contrast, it can be argued that the legacy of the goods and services tax is widely underappreciated. In this case, it is not at all clear that another leader or another party would have taken the very real political risks in introducing a major visible tax of such magnitude, and extending this tax to a vast swath of the economy previously untaxed. Despite the huge unpopularity of the GST at the time, it has proved to be a major contributor to the success of both the Free Trade Agreement and subsequent efforts by the Liberal government of Jean Chrétien to grapple with the federal deficit after 1993. For the GST not only boosted federal revenues, but also effectively gave Canadian exporters a 13.5 percent boost — since GST is not charged on exports, while the MST was applied to all manufactured goods, regardless of who bought them.

However, where the Mulroney record is perhaps most underappreciated is in the realm of foreign policy. While defence policy during this period suffered from an excess of enthusiasm for new military spending followed quickly by an excess of enthusiasm for cutting the defence budget, Mulroney took a number of important foreign policy initiatives and embraced a number of changes in foreign policy over his nine years in power. While one can disagree about whether these initiatives were good or bad, there can be little doubt that Mulroney — aided by Joe Clark as his secretary of state for external affairs — was one of the most activist prime ministers in foreign policy in the twentieth century.

On foreign policy, Mulroney is often best remembered for his attitude towards apartheid in South Africa. And there can be no denying that Mulroney brought to the South Africa file a personal anger at apartheid that was both unusual in itself, and unusual in the degree to which this anger was translated into policy. But the foreign policy record of the Mulroney government was much wider and diverse.

During his time in office, Mulroney withdrew Canadian forces from Europe, although the withdrawal was motivated by the desire to reduce expenditures than for strategic reasons. The government also withdrew the Canadian contribution to the United Nations peacekeeping operation in Cyprus, arguing that peacekeepers had become part of the problem and were hindering the development of peace there. Mulroney also departed from traditional Canadian foreign policy positions by arguing in favour of the use of force in humanitarian intervention and pushing for a more activist role in pushing governments to observe human rights and good governance. One example of this was the tough response of the Canadian government to the massacre in Tiananmen Square in June 1989. Another example was Mulroney’s personal initiative on children’s rights.

Mulroney also used personal diplomacy to good advantage on international environment policy, playing an active role in the Rio summit in 1992. On development assistance, the Mulroney government actually considered the idea of untying foreign aid — for much longer than the usual nanosecond it takes for entrenched interests to assert themselves. Under Mulroney, Canada was an active multilateralist, joining the Organization of American States, opposing American unilateralism, and arguing for multilater- al solutions to such conflicts as the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait.

One of the most important foreign affairs legacies was Mulroney’s initiative to put in place a francophone summit similar to the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting. Prior to Mulroney’s arrival, efforts to create a francophone summit had always foundered on the highly centralized vision of the Canadian federation articulated by Pierre Elliott Trudeau, and the efforts to keep the role of the provincial governments on the international stage as limited as possible. Working with both Parti Québécois and Liberal governments in Québec, Mulroney broke through the logjam and oversaw the establishment of an international institution in which Canada’s francophone provinces play a permanent and legitimate role.

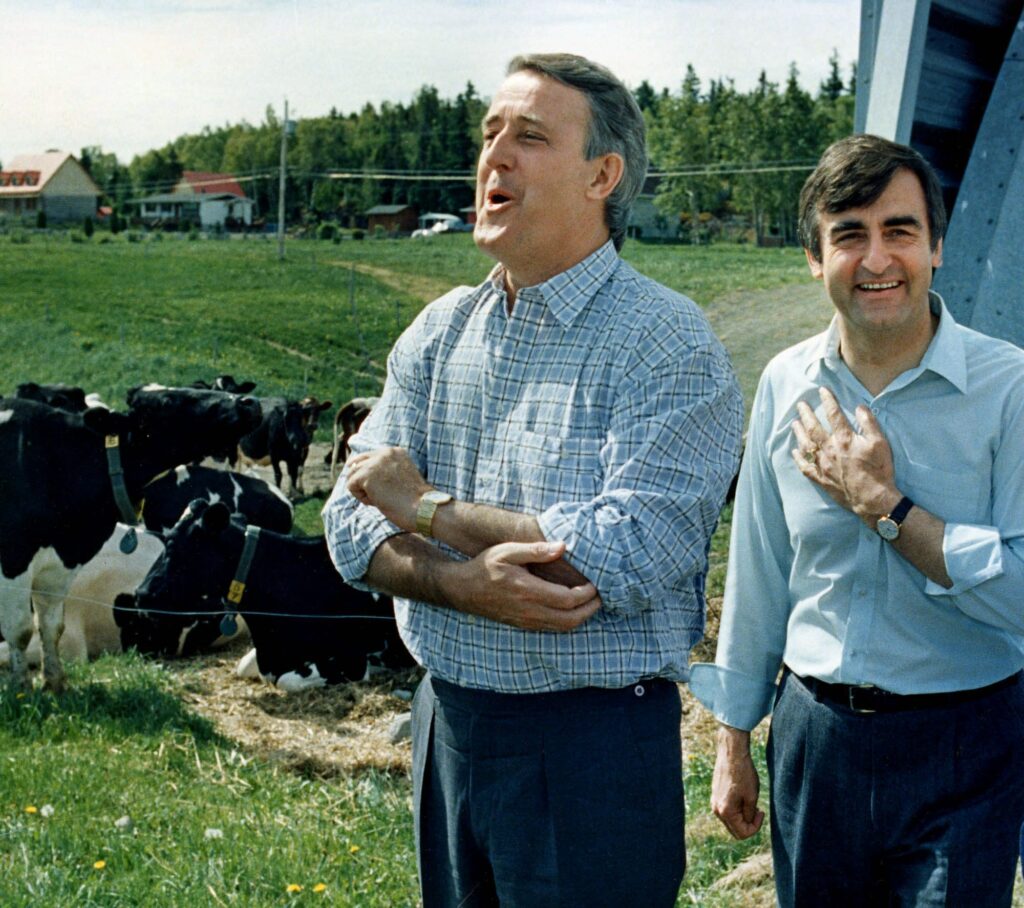

In Canadian-American relations, Mulroney made good on his election promise to “refurbish” the relationship. While some of the more symbolic elements of that refurbishing might have been corny or cloying (Brian and Mila Mulroney and Ronald and Nancy Reagan singing When Irish Eyes Are Smiling together at the Québec summit in 1985 has become the icon of choice for corny and cloying), there can be little doubt that during the Mulroney years, the Canadian prime minister enjoyed a level of access and influence at the White House not seen before or since.

This is not to suggest that there were no conflicts in Canadian-American relations during this period. Trade disputes proliferated, despite the free trade negotiations. There was no agreement on Reagan’s pet Star Wars project. There was conflict over American extraterritoriality on Cuba, American unilateralism towards international institutions, American policy in Central America, and American challenges to Canadian sovereignty in the Arctic. And acid rain was as important a source of conflict during most of the Mulroney years as it had been during Trudeau’s final term of office.

What was different about the Mulroney years is how conflicts in the relationship tended to be managed. Policy disagreements were always conducted with the shadow of the future very much in mind, and always with a recognition that the Canadian-American relationship was paradoxically hugely complex but at the same time fragile and easy to damage. A good example was the so-called “polite no” delivered to the US in 1985 on Star Wars. The politeness of the refusal to participate was not only designed to see if Canada could have its cake and eat it too on the defence contracts likely to ensue from the Strategic Defense Initiative, but also to soften the impact of the absence of Canada and the legitimacy that Canadian approval would have lent to SDI.

Mulroney also proved to be a good diplomat and negotiator with the US, and able to defend Canadian interests. The thorny and highly political issue of Arctic sovereignty was removed from the Canadian-American agenda, with a major concession provided by the United States on this issue, almost entirely as a consequence of Mulroney’s personal relationship with Ronald Reagan. The acid rain issue likewise disappeared from the agenda (even if acid rain itself has not entirely disappeared), partly because of Mulroney’s close relations with George Bush père. On extraterritoriality, Ottawa took the important step of introducing legislation make it an offence to obey the extraterritorial application of foreign law.

I have argued that Mulroney’s time in power will be marked by mixed results and different kinds of legacies. To date, those legacies have in large part been clouded by the extraordinary antipathy he ended up provoking in Canadians — an interesting psycho-political dynamic that in itself deserves further study. But with the passage of time, and as the results of some of the initiatives introduced by the Conservatives in both domestic and foreign policy become more evident, it is likely that Mulroney will be judged rather differently by history than by those who so readily voted for anyone but a Conservative in 1993.