In geophysics the term “fault line” describes a fracture in a large area of rock. These fault lines emerge as a result of shifts in the plates that make up the surface of our earth. Energy released from these shifts causes most of the world’s earthquakes.

What happened in the 41st general election could be described as a political earthquake, and what’s left standing in its aftermath is very different from what stood before. Political monoliths that existed for generations have come crashing down to be replaced by new builds of unknown structural integrity.

What are the new fault lines of Canadian politics? Some of them are defined by geography, some of them are defined by demography, and still others are defined by attitudes. In this article we will trace these new fault lines and show you how they redefine the public opinion landscape that will drive our national politics for the foreseeable future.

Over the last three national elections Ipsos Reid has conducted massive online election day polls with our partners at Global Television. These polls serve two purposes. First, they allow us to track how voters are casting their ballots throughout the election day so we can accurately predict the final results in terms of both popular vote and seat counts (which we’ve done successfully in all three elections). Second, apart from telling us how they voted, respondents also answer a 140-item questionnaire that probes their views on various topics and aske about their demographic backgrounds. Put simply, our election day polling is a freeze-frame screen shot of exactly what voters were thinking and doing on May 2.

Our exit poll for the 41st general election captured the responses of nearly 40,000 voters. This has created an incredibly rich and detailed data set that captures the political views of some rarely studied subsegments of the electorate. For example, we interviewed:

- 1,394 voters from the gay and lesbian community

- 2,873 voters who describe themselves as visible minorities

- 582 voters who say they are Aboriginal

- 250 Muslim voters

- 601 Jewish voters

- 228 Mennonite voters

- 178 Caribbean immigrants

- 6,551 residents of gun-owning households

- 2,689 self-employed voters

- 1,502 teachers or professors

- 145 farmers or fishers 192 construction workers

- 79 members of the military

- 7,855 advance poll voters

- 8,991 voters who say they logged on to Facebook to discuss public policy and political issues

To say the least, this data set is overwhelming. What we provide here only scratches the surface of the new tectonics. We are hoping that scholars who have an interest in voter behaviour will continue to explore our data set in the years to come. To this end, as with all of our previous exit polls, the original data set has been donated by Ipsos Reid to the Laurier Institute for the Study of Public Opinion and Policy at Wilfrid Laurier University in Waterloo, Ontario.

Stephen Harper clearly understood the relationship between voting Conservative and gun ownership. Harper’s strategy to use a vote on a private member’s bill to create cross-pressures back home for rural NDP and Liberal MPs on the long-gun registry clearly had an impact on election day.

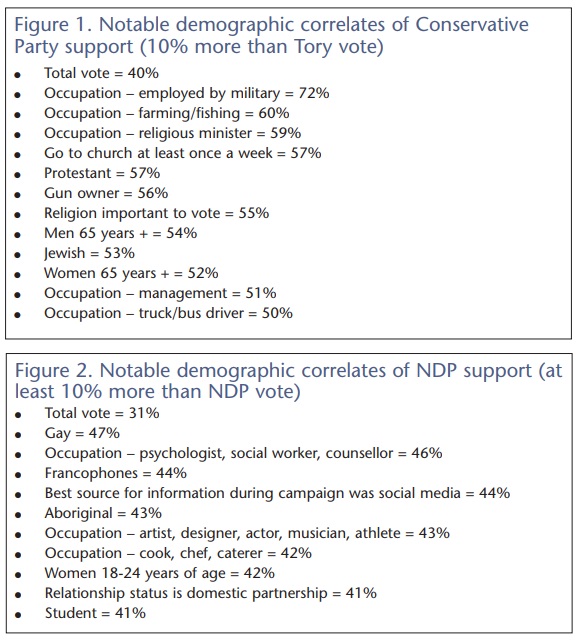

Returning to the fault lines of Canadian politics, it’s very clear from our research that Stephen Harper and the Conservatives have put together a coalition that is demographically consistent and coherent. As figure 1 shows, Tory voters in this last election are rooted in what we like to call “old Canada.” Old Canada is the Canada that hasn’t been dramatically impacted by the waves of immigration that have transformed our major cities. What we see in the Tory vote is an overrepresentation of older men and women, traditional occupations, the Protestant churches (Tories like to put on their Sunday best) and gun ownership. While it isn’t reflected in figure 1, there’s also a positive correlation between voting Conservative and income. Put simply, the more money you make, the more likely you were to vote Conservative on May 2.

Figure 1 also shows that Stephen Harper clearly understood the relationship between voting Conservative and gun ownership. Harper’s strategy to use a vote on a private member’s bill to create cross-pressures back home for rural NDP and Liberal MPs on the long-gun registry clearly had an impact on election day.

On the issue of the “ethnic vote,” there’s been a lot of speculation since the election that Stephen Harper’s unwavering support of Israel would help the Conservatives with Jewish voters (who have historically been core Grits). Figure 1 shows that this speculation is correct. For the first time Canada’s Jews voted for the Tories. While this meant little in terms of the overall election results, it played a very important role in a handful of critical ridings in the GTA.

In terms of identifiable groups of immigrants, the exit survey shows that the Tories did reasonably well among new Canadians, but not necessarily in the way that some pundits have suggested. Foreign-born voters who went Tory in this election tended to have been in Canada 10 years or longer. Our hypothesis is that these are immigrants who are now economically established in Canada, have become middle class and are now voting like Canadian-born members of the middle class. To look at them as “ethnic voters” is missing an important distinction.

A part from the obvious English/French fault line that lies between NDP voters and Tory voters, sexual orientation is even more of a stark difference (figure 2). If you’re gay in Canada, it’s a pretty solid bet that you voted NDP in this election. Additionally, if you have a nontraditional domestic living arrangement, work in a helping profession or are a member of the creative class, you are overrepresented in the NDP coalition. Add in young women, students and online activists, and you see who the NDP can thank for its orange wave.

From a demographic perspective, this is a radically different NDP than the one that emerged from the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation in the early 1960s. NDP 1.0 was a loose coalition of farmers, progressive Christians and labour unionists. In more recent times the NDP also rolled in left-wing academics, social activists of various stripes and progressive municipal politicians (like Jack Layton).

NDP 2.0 has all but lost its agrarian roots. Canada’s farmers left for the Tories a long time ago. The progressive Christian element, while still part of the party’s activist class, has not kept its flock under the NDP banner. NDP 2.0 voters are a secular coalition.

NDP 2.0 has all but lost its agrarian roots. Canada’s farmers left for the Tories a long time ago. The progressive Christian element, while still part of the party’s activist class, has not kept its flock under the NDP banner. NDP 2.0 voters are a secular coalition.

Interestingly, NDP 2.0 is potentially a tighter coalition than NDP 1.0. Today’s NDP voters are activists, the creative class, plus the marginalized, the oppressed and those who care about and help them. And while NDP 2.0 is decidedly more francophone than NDP 1.0, it would be a mistake to think that these are separatist voters slumming with another party. Yes, many new NDP voters voted BQ in the past. But it was more for the Bloc’s progressive approach to public policy issues than it was for its desire to seek an independent Quebec. The truth is that most hard-core separatists stuck by the BQ in this election. Francophone NDP voters are soft nationalists — they have their hearts in Quebec and their heads in Canada.

If the Tories appealed to stodgy Canada, and the NDP appealed to activist and hip Canada, who did the Liberals appeal to? As figure 3 shows, it was to intellectual Canada. Canada’s intellectuals were overrepresented in the Liberal ranks. But the Grits also did better with Muslim and Hindu voters. This finding, along with what we know about the immigrants who voted Tory, puts to rest the theory that the Tories built their victory in the suburbs of our bigger cities by appealing to immigrants from countries that have more traditional value systems. If this were the case, 52 percent of Muslims in our sample wouldn’t have voted for the Liberals.

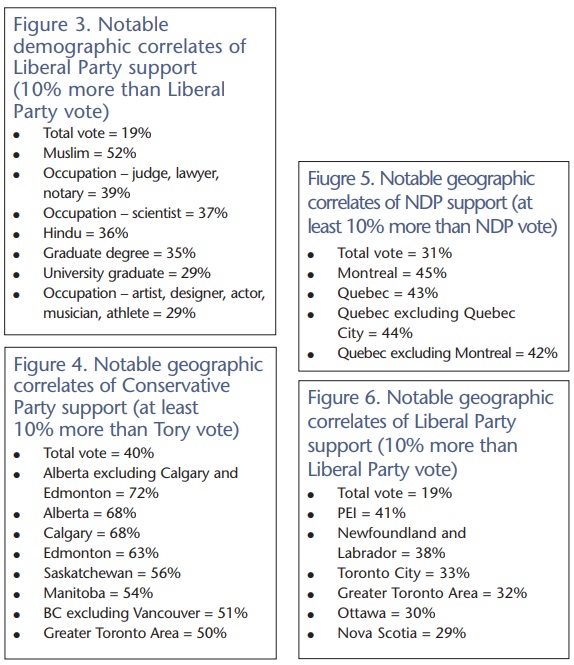

In spite of its breakthrough in the Greater Toronto Area (GTA), the Conservative Party continues to have its deepest roots in the West — especially Alberta (figure 4). While the Tories do a little worse in the western cities, it’s a matter of degree as opposed to a meaningful difference in outcome.

While the rise of the NDP coupled with the meltdown of the Liberals and the Bloc consumed most of the ink in post-election analyses, the most significant change in this election in terms of impacting the actual outcome was Harper and the Conservatives bringing the “coalition of taxpayers” into the Tory fold. That’s why the Tories won half of the votes in the GTA.

The Tory victory in the GTA started with the most recent municipal elections in Ontario. Suburban voters (the coalition of taxpayers), who stayed away from the last two municipal elections, decided to show up this time. They rose up and punished municipal governments and city councillors whom they believed to be out of touch with the values, needs and desires of the urban and suburban middle class. What started with a municipal workers’ strike in Toronto ended with Tory gains in the GTA on May 2.

How were the Tories able to position themselves as agents of change after being in power for five years? It’s because, for residents of the GTA, the Tories were a new option — they hadn’t really considered the Conservatives as a serious choice since 1988 when the old Progressive Conservative Party won a sizable number of seats in both Toronto and the GTA. And Harper’s message of certainty, stability and fiscal prudence resonated with Mayor Ford’s similar message, and carried the day for the Conservatives.

While the Conservative story is about dominating in the West and breaking through in the GTA, the NDP story is all about Quebec — especially Montreal. Nationwide, 31 percent of Canadians voted for the NDP, but 45 percent of our exit poll respondents in Montreal voted NDP, along with 42 percent of Quebecers outside of Montreal (see figure 5). No other significant jurisdiction in Canada voted 10 percent or more above the national average for the NDP. This shows that the NDP’s success in this election was essentially appealing to voters in one province, not on a national basis. In other words, the orange wave crested only in Quebec.

What the Liberal Party of today lacks is a significant geographic clustering of support that will yield a meaningful number of seats. The Grits are mostly competitive in Atlantic Canada, Toronto and Ontario’s second-largest city, Ottawa. This is hardly a winning formula for the future. Toronto, with its large number of seats, is essential to rebuilding the Liberal Party’s support, but popularity in Atlantic Canada, while nice to have, will not get the Liberals back into contention in a national election (figure 6).

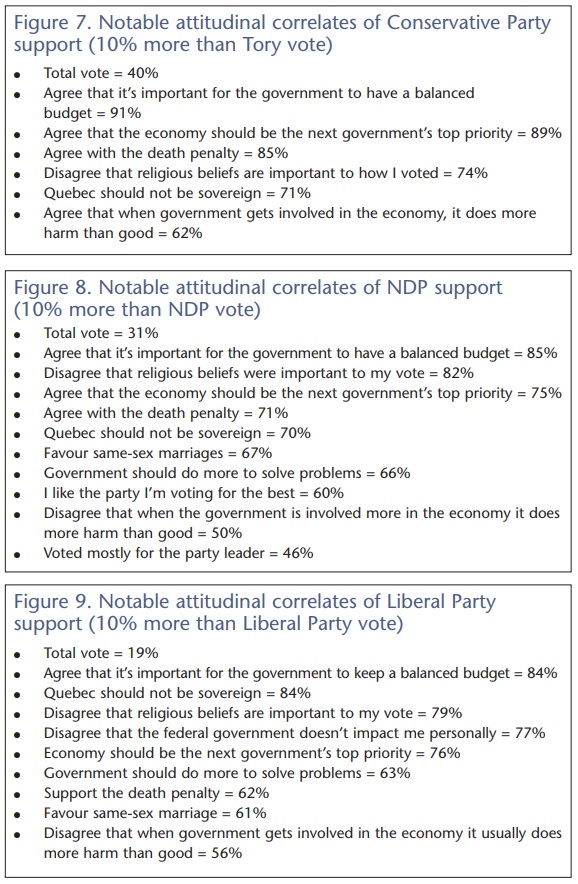

Today’s Tories are mostly about the economy (figure 7). As we’ve said, they are a coalition of taxpayers. While there are clearly some moral undertones to the personal values of Conservative voters, they are united by them, as opposed to being divided by them. This is a stark contrast to Brian Mulroney’s coalition of Progressive Conservatives, who were a combustible alliance of western Conservatives, Red Tories from Ontario and soft Quebec nationalists. Moral issues for the old PCs were toxic in terms of party unity. This doesn’t seem to be the case for today’s Tories.

While New Democrats can agree with the Conservatives on balancing the budget and the need for the government to prioritize the economy, the NDP is at the opposite end of the scale when it comes to having secular and progressive values. The two examples that spring up in figure 8 are the role that religious beliefs play in personal voting decisions, and support for same-sex marriage. Also, NDP voters are more likely to believe in a dirigiste government relative to the economy, while Tory voters think the less government involvement in the economy the better.

Nationwide, 31 percent of Canadians voted for the NDP, but 45 percent of our exit poll respondents in Montreal voted NDP, along with 42 percent of Quebecers outside of Montreal. No other significant jurisdiction in Canada voted 10 percent or more above the national average for the NDP. This shows that the NDP’s success in this election was essentially appealing to voters in one province, not on a national basis. In other words, the orange wave crested only in Quebec.

This suggests that there could be cross-party support for Harper and the next NDP leader working to reduce the deficit and focusing on the economy, but on little else.

What’s especially notable in figure 9 is how little the attitudes of Liberal voters differ from the attitudes of voters who supported the New Democrats. What this suggests is that the attitudinal fault lines actually place the New Democrats on the same side of the divide as the Liberals. Stated another way, New Democrats and Liberals seem to think alike. Are the party affiliations distinctions without a difference? Are New Democrats, as former prime minister Louis St. Laurent famously said, just Liberals in a hurry? If they are, the future of the Liberal Party is precarious indeed.

Our election day poll shows that the new fault lines of Canadian politics are different from what we’ve experienced before. Are we seeing the emergence of the “creative politics” that John Porter talked about in his 1965 book The Vertical Mosaic? That would mean the demise of the brokerage parties of the past (which focused on what Porter describes as tangential debates over national unity and regional interests) and the emergence of true parties of the left and right that focus on fundamental questions of economic power and class interests.

Our election day poll shows that Porter may have been ahead of his time. Prime Minister Harper has put together a modern Conservative coalition that has the potential to be an enduring force in Canadian politics. This new coalition has cohesiveness in terms of demography that the Progressive Conservatives of the past never had. The new Conservatives also share fundamental beliefs that differentiate them from voters from other parties. They are a national coalition of “taxpayers.” They also share a demographic and regional profile — they are old Canada, they are focused in the West, they have a new home in the GTA, and they own rural Canada. These are the new fault lines at work.

While the conservative side of the three major fault lines seems to have been worked out, the same can’t be said for the progressive side. The New Democrats clearly have the upper hand with the newer and hipper Canada. Yes, they dominate in Quebec, but they also have appeal in our bigger cities. And it is in our bigger cities that the battle for the progressive vote (between the Liberals and NDP) will take place. So will the Liberals or the New Democrats capture our urban intellectuals and newer immigrants? For these voters, the Conservatives are not an option, and they will vote NDP if they can’t vote Liberal.

To be clear, these trends are about more than party leadership. Of course who both parties pick as their next leaders will have an impact on their short-term marketability, but a careful review of our data shows that this is about more than just party leadership. Progressive voters are being drawn to the NDP because the new tectonics of Canadian politics are driving them there. This, in our view, will be the political story to watch over the next four years.

Photo: Shutterstock