If Canadians needed a wake-up call to the power of regional blocs and the pace of political integration within the European Union, we got it last October with Canada’s failure to secure a seat on the Security Council as a member of the Western European and Other Group (WEOG).

There has been much ink spilled in examining the entrails — the best is contained in a recent piece for the Canadian Defence and Foreign Affairs Institute by Dalhousie Professor Emeritus Denis Stairs. He writes, “The underlying forces at work actually have much more to do with fundamental changes in the composition of the international state system and in the structure of the power-hierarchy within it. In relative terms, Canada has simply become much less significant than it used to be as a player in international security affairs.”

There is much we should do, including a thorough reappraisal and then reinvestment in our diplomatic service. But the first and easiest step should be to extricate ourselves from the WEOG. Like the UN Security Council, this is an anachronism that made sense in 1945 but not today. We are lumped, along with Australia, New Zealand and Israel, in what is now a consolidated regional union in which we have neither place nor standing. A German diplomat once defined us as a “regional power” without a region. Our G8/20 membership accords us a global ranking. We have place within the North Atlantic, the North Pacific and the Arctic but most of all within North America and the Americas.

Geography to a large extent is destiny. We’ve created the most successful bilateral relationship in the world with the United States. It will always be our primordial relationship. But alignment with the colossus has meant we’ve been reluctant to look further south on the continental map. We committed to the Americas, joining the Organization of American States (OAS) in 1990 and then the tripartite NAFTA in 1993. The Harper government appointed a secretary of state for Latin America when it came to power in 2006. But notwithstanding the fine words and diplomatic commitment, both bilaterally and at the OAS, our effort has lacked heart and soul.

Part of the problem is that we get bogged down in the debate between bilateralism and trilateralism.

The arguments for bilateralism are compelling. If the asymmetries between Canada and the US are significant, they are even greater with Mexico. As the Canadian ambassador, Michael Kergin, remarked in 2001: “The problems are different; the institutions are at different levels of development; and our respective international roles, responsibilities and memberships are different.”

There has never been the kind of security partnership, let alone defence alliance, with Mexico that is enjoyed between Canada and the United States. Resources offer another challenge: Mexican sensitivities mean that the kind of energy accord enjoyed by Canada and the US is not on the cards. Trilateralization, as former US Ambassador Gordon Giffin and former Canadian Deputy Prime Minister John Manley wrote in a joint 2009 op-ed in the Globe and Mail, is not the solution because the three societies and economies are not at “parity.” If a North American community is to be realized, they concluded, it would be because of the leadership shown by the “northern members.”

These are intelligent and irrefutable observations in the context of Canada-US relations.

But the dichotomy between trilateralism and bilateralism can be overdrawn, because both approaches can and should be pursued in parallel and with mutual support, as the US has long demonstrated. To do otherwise defies US geography and ignores American history.

The US commitment to the Americas dates from the Monroe Doctrine (1823) declaring that foreign interference or influence in the Americas would not be countenanced. The doctrine has been applied at various times, notably against France when Maximilian was proclaimed Mexican emperor, through the Spanish American Wars and, most notably, against the Soviet Union during the Cuban Missile Crisis.

It also fails to appreciate the new reality of American political demography.

Today, Latinos are the largest “minority” group in the US, making up 15 percent of the population and projected to be 29 percent of all those living in the United States by 2050. In the 111th Congress (2009-11) there were 25 Latino members and for all but six, Latinos were the majority of the district population.

Like the Irish and Italians before them, Latino Americans are increasingly participating in politics. They have moved from the ward to gubernatorial and senatorial elections. It is quite likely that this century will count more Latino than black presidents.

Leaving Mexico out of greater continental integration is inconceivable for the US.

Whether we hear it or not, we are reminded of this by our American interlocutors whenever the issue arises. In the US bureaucratic mindset, trilateralism is doctrine, and it has been institutionalized into the bureaucratic structures, with both the National Security Council and the State Department grouping Canada and Mexico together.

Like the UN Security Council, this is an anachronism that made sense in 1945 but not today. We are lumped, along with Australia, New Zealand and Israel, in what is now a consolidated regional union in which we have neither place nor standing.

While for many years we ignored our Latin neighbours south of the Rio Grande, the Americans have never thought this way. By embracing the Americas we also play back into our principal relationship with the United States. When successive administrations, especially since Ronald Reagan, think strategically about North America, they think trilaterally and continentally.

A quarter of US exports flow to the Americas south of their border (in contrast to just 3 percent of Canadian goods). The combined population of the Americas south of the Rio Grande gives them the potential over the coming decades to develop into a market as important as that of the EU, China and India. Growth rates are predicted to be 4.1 percent a year for the next five years — double those of the G8 economies. The Chinese get it and are making significant investments. And with China competing with America for influence, there are geopolitical reasons for our making our presence felt because we also have significant interests in the Americas.

Canada has significant people-to-people ties with the Caribbean (and it has long been our most reliable partner when we seek a UN Security Council seat). The Bank of Nova Scotia opened its first branch outside of Canada in Kingston, Jamaica, in 1889 and Canadian banks are now found throughout the Caribbean. We are committed to Haiti for the long term. Our foreign direct investment (FDI) in the Americas outside the US is three times that in Asia. We’ve created a network of free trade agreements (FTAs), far more in Latin America than in Asia: with Mexico, Costa Rica, Chile, Colombia, Peru. The Panama FTA is before Parliament; we are negotiating with Honduras and the Caribbean Community; and we’ve started discussions with MERCOSUR. We are now the number one investor in Chile.

We are funding governance programs in Guatemala and helping in the training of Central American armed forces to take part in UN peace-keeping operations. Working with the OAS, we’ve helped to make Central America a mines-free zone after decades of civil war.

Despite bumps in the road, we have a growing strategic relationship with Brazil, the bookend to Mexico in Latin America. Canadian pension funds are invested hugely in Brazil and, with Brookfield, are among the largest holders of foreign investment in real estate in the country. RIM opened its first plant there last year. Canadian investment in Brazilian mining is significant, and while Brazil is poised to become an oil producer there are obvious opportunities for the Canadian energy sector.

As a recent report conducted by our Department of Foreign Affairs concluded, we need “more concrete evidence on the ground of Canada’s interest.” Our relevance in the region will also be measured in terms of our capacity and willingness to participate in the broader social, political and economic agenda.

Embracing the Americas should start with Mexico.

Unfortunately, Mexico has suffered from a lack of strategic consideration by Canada. As a result, when we do act, it can be with the same kind of heavy-handedness for which we criticize the US. In the case of the imposition of the visa requirement in July 2009, we applied a hammer to amend our refugee determination process, a made-in-Canada problem.

For the Mexicans it was a slap in the face. Former president Fox voiced what the diplomatic cables could not: “We Mexicans, we are not criminals, we are not terrorists. I don’t know where the confusion is and why that decision was taken,” he said. “Instead of imposing visas, we should be building bridges, bridges of friendship, bridges of understanding. That’s the way to go. Isolating yourself has no purpose. I don’t know what the fear is in Canada.”

“Refugees?” he continued, “You have laws for that. You can give them asylum or not give it to them. That has nothing to do with visas.”

The effect on Mexicans’ travel to Canada? Visits for 2009 shrank to 161,000 from the more than 250,000 visitors in 2007 and 2008. Canada had been the second preferred destination for Mexicans after the United States before 2009. All this to contain the 9,000 refugee claims filed in Canada by Mexicans in the six months before July 2009.

There are undeniable problems in Mexico — gridlock in government, statism and corruption. The current treadmill of relying on tourism, remittances from the United States and oil money is unsustainable. Northern border towns like Juarez are war zones, underlining that the drug war is largely built on American demand. Lurid headlines featuring heads detached from corpses — the premise for Carlos Fuentes’ latest novel, Destiny and Desire — are a daily reminder of its existential war with drug cartels.

But look behind the headlines.

Canadians continue to visit Mexico in record numbers, undeterred by the Foreign Affairs travel advisory urging Canadians to “exercise a high degree of caution” when travelling to Mexico. Between 2005 and 2010, Canadian tourist visits have doubled from 675,000 to over 1.5 million. Canadians now make up nearly 15 percent of tourists visiting Mexico. The Canadian community living in Mexico is estimated at around 75,000. It is reckoned that Mexicans living in Canada number around 50,000, including the former designer for the Mexican currency, who is now applying his skills to the Canadian dollar. Notwithstanding the self-inflicted drop-off in Mexican tourism to Canada, there are more than 400 agreements between universities in Canada and Mexico to foster academic exchange with approximately 10,000 Mexican students currently in Canada. We could do more with Mexican universities and use International Development Research Centre (IDRC) funding to support its think tanks.

Canadian investment is significant and growing. Mexico is Canada’s third-largest trading partner after the United States and China. Mexico is Canada’s fourth-largest export market, surpassed only by the United States, Britain and China. More than 2,500 Canadian firms are active there. Canadian mining firms are major players (representing 70 percent of FDI. Canada is Mexico’s fourth-largest source of foreign investment. Walk down any of Mexico City’s main streets and you will spot a Bank of Nova Scotia, now the sixth-largest bank in Mexico (and the third-biggest bank in Peru and the seventh-biggest lender in Chile). You can also find other Canadian companies like Magna, which has over 30 plants in Mexico. RIM produces BlackBerrys in Mexico for the global marketplace. Mexico is a leading importer of Canadian food products (wheat, canola, processed foods), worth some $1.4 billion each year. Walk into any supermarket and you are likely to find Canadian products.

The supply chain dynamics that underpin the Canada-US relationship now embrace Mexico. Bombardier now builds the majority of the subway cars for the Mexico City Metro, which moves over 6 million people per day in a city of 20 million people. Aerospace facilities in Queretaro also build components for the full line of Bombardier aircraft, including the tail assembly for the Global Express, which is shipped from Queretaro to Montreal for final assembly. But the NAFTA engine needs reignition.

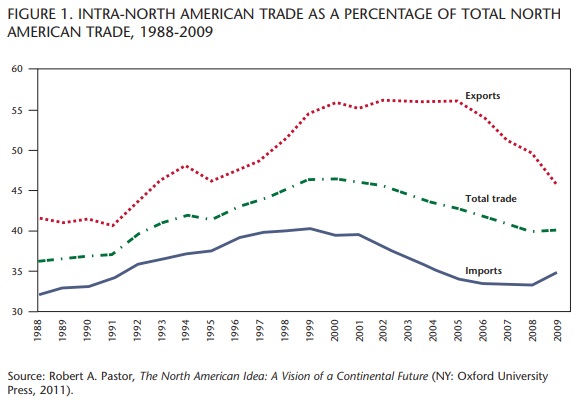

The gains in trade, and they are significant, were mostly realized in the first decade, at least for the Canada-US and Canada-Mexico relationships. Between 1990 and 2001, interregional exports as a percentage of total exports rose from 43 percent to 57 percent (figure 1) — the level achieved by the EU after five decades. While Canada and Mexico remain America’s top two markets, during the past six years intraregional exports have fallen back to 51 percent. North America’s share of world gross product has declined from 35 percent to 27 percent. The EU has moved ahead of NAFTA. China surpassed Mexico as the second largest exporter to America in 2003, and in 2007, China passed Canada to become America’s biggest source of exports.

The pillars of the architecture supporting NAFTA — the leaders’ summits and joint cabinet meetings, the Security and Prosperity Partnership and the North American Competitiveness Council — are, respectively, on life support, dead or zombified. When the NAFTA partners meet at leader and ministerial levels, increasingly it resembles a doublepartner dance featuring a trio of bilaterals, with the US as the principal partner.

The 2010 leaders’ summit was postponed until the spring of 2011 and then further postponed. The leaders’ summits are important because they create the personal relationships that get things done. They have achieved progress on issues beyond trade and investment, including, for example, a coordinated response to pandemics and a focus on combating drug trafficking.

Foreign ministers met in Wakefield, Quebec, for a few hours on a snowy December morning in late 2010. Their main item for discussion was Haiti. When the leaders met in Guadalajara in August 2009, their focus was the political crisis in Honduras. Security has become common cause for the three countries and has spurred along the trilateral process. We now coordinate our actions to strengthen the judiciary, the police and public institutions in Central America. But we also need to focus on the issues that further the NAFTA idea: environmental collaboration, a continental energy strategy and a continental transportation system linking our roads, rail, air and ports.

There has been some, but not enough, scholarly attention to Mexico and the Americas at Canadian institutions. The Canadian Council of the Americas, with regional branches across Canada, is a booster for trade and commerce. There is the Canada-Mexico Partnership and Initiative. The Canadian Foundation for the Americas (FOCAL) keeps the flame burning. Canadian International Council president Jennifer Jeffs and the new president of Lakehead University in Thunder Bay, Ontario, Brian Stevenson, have an abiding interest and good ideas. For intellectual capital we also need to look south to the work of American and Mexican scholars, including Isabel Studer, Bob Pastor, Abe Lowenthal, Carol Wise and Denise Dresser.

Like the Irish and Italians before them, Latino Americans are increasingly participating in politics. They have moved from the ward to gubernatorial and senatorial elections. It is quite likely that this century will count more Latino than black presidents.

The lack of a strategic partnership with Canada, writes former Mexican diplomat Isabel Studer, “has also opened the door for letting small problems acquire a bigger dimension than desired.” Studer, who now directs the Centre for the Study of North America, writes that “the adoption of unilateral decisions that have been unnecessarily harmful for both countries and the constant bureaucratic urge to formulate new empty initiatives that, while showing the formal commitment to develop a strategic partnership between the two countries, have no real substance.”

We have never put the effort into defining a Canada-Mexico strategic partnership. Former ambassador Michael Wilson acknowledged this in a 2007 speech to the Empire Club when he said, “Until recently, Canada did not pay sufficient attention to our hemispheric neighbours. This is changing. The government has stated its intention to accord a greater priority here, to a region where we have significant political and economic interests.”

The provinces, especially the premiers, have understood and put more effort into the relationship than has been the case at the federal level. As Bob Pastor makes clear in his new book The North American Idea: A Vision of a Continental Future, there is opportunity for deeper North American integration, which will benefit each partner. Argues Pastor, “We need to start over with a big North American idea, one based on the simple premise that all three countries benefit when one succeeds, and we are all hurt when one fails.”

Parallel with the new Canada-US initiative launched around perimeter security, the expediting of people, trade and investment and regulatory compatibility, we need to develop a coherent strategy toward Mexico that looks at our integrated trade and investment. Identify opportunities for common cause, as we have already demonstrated in pandemic planning in the wake of H1N1. We both, for example, have shared interests in curtailing US gun imports, in securing better access for our trucking, in jointly taking on US agricultural subsidies.

Most of all, Mexico needs help with institution building. We have much to share in training an independent judiciary, reliable policing and managing pluralism. If we can provide 1,000 trainers in Afghanistan, then surely we can do more for Mexico, where our interests are vastly more important.

Self-interest alone should motivate us. If things go badly for Mexico in its war with the drug cartels, politics and perceptions of unequal treatment towards the “gringo” northern cousins will make it very difficult for any US Administration to grant “special” dispensation on the northern border.

Mexico should be our main target for aid and development. Mexico is a country with a young population. Almost half of its 110 million citizens are under 30. Mexico needs jobs and opportunities: schools and hospitals, roads and infrastructure to build a new social contract. Putting Mexico at the top of our development agenda would signal that we are serious about the Americas. We will reap geopolitical rewards in our relationship with the US, our primordial relationship. It will also fuel the trade and commerce that guarantees our prosperity. The World Bank’s 2010 annual report, Doing Business, declared Mexico the easiest place in Latin America to run a company. The International Monetary Fund says Mexican economic growth will eclipse that of the US and Canada from now until 2015.

Goldman Sachs predicts that in 40 years Mexico will be the world’s fifth-largest economy, bigger than either Russia, Japan or Germany. Smart countries are strategic in their relationships. It’s time for Canada to embrace the Americas, starting with Mexico.

Photo: Shutterstock