The “right to repair” has become a hot topic in recent months among Canadian policymakers, consumer-rights groups and the public. This builds on a growing global consciousness of planned obsolescence and the short lifespan of electronic devices and products.

Planned obsolescence is purposely shortening the useful life of goods through various means. This can include using poor quality, non-durable materials or flooding the market with updated products that don’t work with existing models. No longer offering support through software updates or replacement parts is another tactic.

On the other side is a movement to make products last longer, in part by making it easier for owners to repair devices themselves or have them repaired by someone other than a manufacturer’s technicians and service networks.

Canada is not alone in its focus on the right to repair. Several U.S. states have successfully passed right-to-repair legislation. Likewise, the European Union has adopted measures that include product standards, mandated availability of spare parts and other pro-repair requirements for device manufacturers.

Following Ontario’s unsuccessful attempt to pass a right-to-repair bill in 2019, it became clear to policymakers in Ottawa that federal leadership was needed. They have since shown a strong interest in legislating reforms with support from all parties.

The empty success of recent amendments to Canada’s right-to-repair bill

The right to repair formed part of the Liberal Party’s platform in the 2021 election and there have been repeated references to it since that time in ministerial mandate letters and the recent fall economic statement.

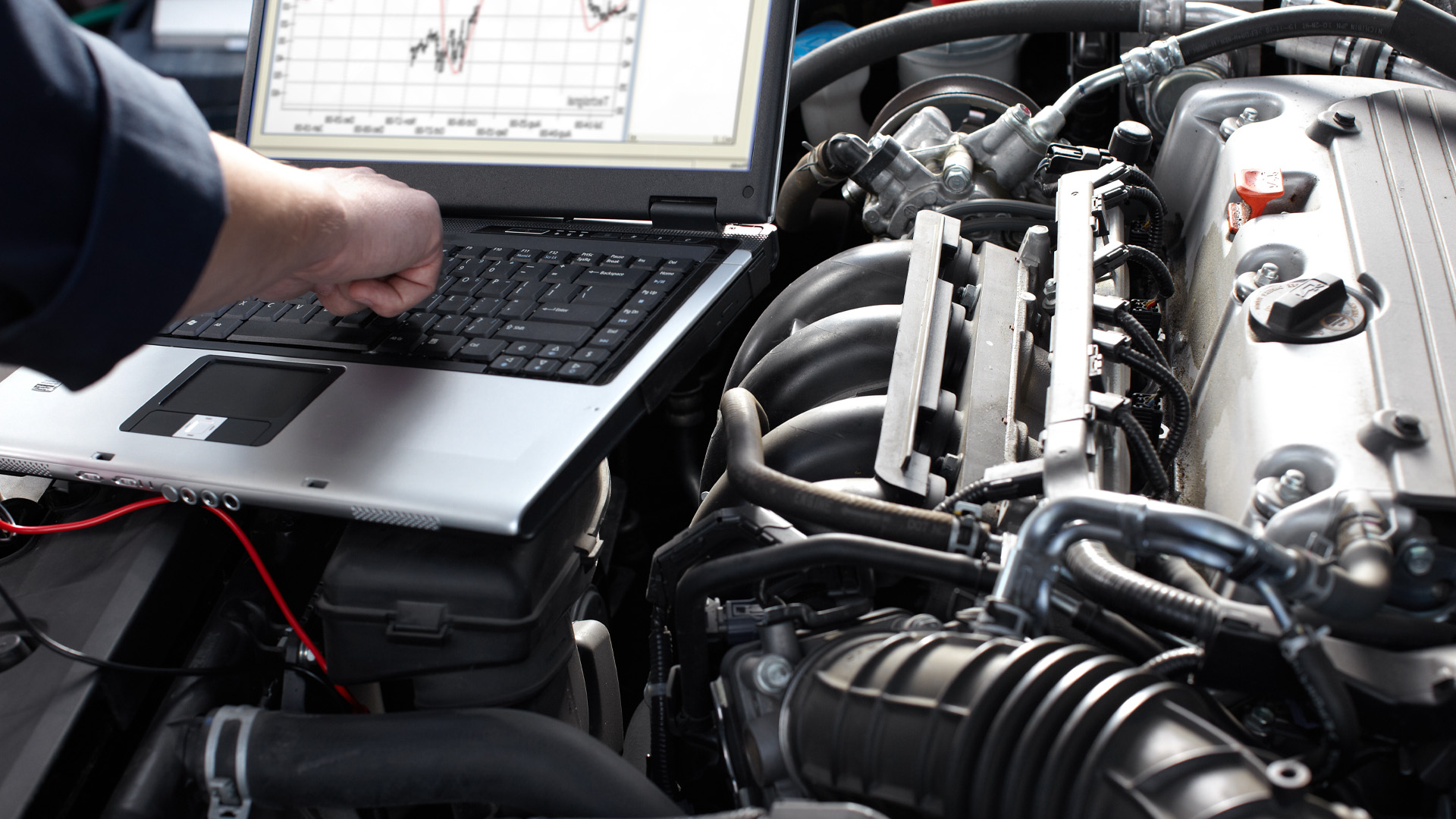

Initial efforts at the federal level have focused on tackling copyright restrictions – also known as anti-circumvention laws – that make it impossible to get around technological protection measures or digital locks used on software and found in almost every computerized or “smart” device, appliance and machine in the world today.

One example of this is the pervasive locks and software controls in modern agricultural equipment and machinery.

Copyright restrictions prevent decrypting or bypassing software controls, even when the purpose is for repairing a device. Often the device’s functions after a repair will be limited unless the fix is authenticated using special software or tools that manufacturers do not normally make available to consumers or independent technicians.

Digital locks can lead to a dead end for many in the repair industry or spur attempts to find unauthorized or legally dubious means to get around these control measures.

The liability and risk posed by anti-circumvention laws on the repair sector is no small matter. In 2017, the Federal Court awarded more than $12 million to Nintendo for unauthorized modification to game consoles by a small company.

The Copyright Act prohibits three categories of activities related to attempts to circumvent protected software:

- Private acts in which individuals bypass software access controls on their own;

- Provision of circumvention services or bypassing access controls for others on a commercial basis;

- Circulation, distribution, manufacture or sale of special tools or technologies needed to evade controls. This is sometimes referred to as “trafficking” in circumvention devices. These could be special cables, software cracks, passwords, patches or encryption keys.

Individuals who repair devices at home – or tinker with and modify them as part of amateur research – are generally engaged in private circumvention, while businesses are more likely to be engaged in the latter two activities. There are exceptions to these rules (for example, making copyright-protected works perceptible to people with disabilities), but “repair” is not among them.

The first major reform effort was in 2021, when Liberal MP Bryan May introduced private member’s Bill C-272 to amend the Copyright Act, but it died when the federal election was called. Fellow Liberal MP Wilson Miao reintroduced it as Bill C-244 in February 2022.

The original bill sought to allow all three of the prohibited activities for the purposes of repair, maintenance or diagnosis of computerized devices. The bill showed promise for a meaningful right to repair in Canada for individuals as well as independent businesses.

But abrupt amendments to the later Bill C-244 without much discussion in May 2023 obscured the bill’s legislative intent. The amendments included a seemingly redundant list of copyrightable works that could be relevant to the proposed repair exceptions.

The emphasis on sound recordings in particular gave reason to question the intent and implication of the changes. Of primary concern was that the legislative language could be used to create a carveout for certain devices or products.

Bill C-244 is now before the Senate, and much more has been learned about the bill’s legislative intent, its amendments and their practical impact on the right to repair in Canada. There have been assurances that fears of a carveout for devices with embedded sound recordings may have been overstated.

But the amendment’s wording continues to confuse repair and repair-related businesses as well as policy advocates across the country. This confusion threatens to leave the repair sector paralyzed and mired in ambiguities around business and legal risks.

Federal policymakers would do well to craft guidelines clarifying the circumstances in which digital locks could be lawfully circumvented for repair, maintenance or diagnosis.

A further concern is that the amendments address only private acts and exclude circumvention services and bypass devices. This drastically narrows the scope of the bill’s original form.

The result is that the bill might do little to help independent businesses doing digital repairs or wanting to distribute or sell special bypass tools. It appears the right to repair envisioned by the bill would be predominantly private, reserved for individuals who are technologically inclined.

One explanation for the bill’s narrow scope could be the government’s international trade obligations under the Canada-United-States-Mexico Agreement. That agreement’s intellectual property provisions limit Canada’s wiggle room to craft new exceptions to copyright law that promote repair – which means the next frontier for Canada’s right-to-repair policy may be at the international trade level.

Whether it be for the automotive aftermarket, medical devices or home appliances, a Canadian right to repair must support secondary markets and independent businesses.

Forward momentum – even if less than perfect – is essential to achieving a meaningful repair policy. At the same time, confusion and concerns remain over Bill C-244 and whether it applies to commercial repair businesses.

Policymakers in Ottawa would be wise to provide guidelines that better explain the repairs intended to be covered by the bill. Otherwise, they run the risk of having achieved a milestone that is primarily confined to the walls of Parliament.