Version française disponible ici.

This is the first of two articles on pandemic management in Quebec.

Epidemiology was a relatively unknown field to most of us, prior to February 2020. With the onset of COVID-19, epidemiologists quickly became prominent figures in the media.

Scientific projections based on mathematical modeling and statistics are crucial tools for shaping public policy. This holds true for epidemiology – especially during a pandemic – as well as climatology, to name just two specific disciplines.

Starting from estimates based on current conditions, these two scientific fields provide policymakers with a degree of predictability. They allow for the creation of a manageable present by identifying the conditions that can be acted upon to produce more desirable outcomes. For example, climatology guides policymakers to make informed decisions about fossil fuel consumption to keep global temperatures at sustainable levels. Although not every policymaker fully embraces these scientific forecasts, without them, the repercussions of policy action (or inaction) would be much more unpredictable.

Such projections are one of the tools experts use to exert influence over policy. By reducing issues to tangible, understandable, and relatively simple dimensions – such as the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions – they help focus policymakers’ attention, thereby narrowing the range of potential solutions.

However, in a democracy, experts are just one source of influence among many. It would be misguided to believe that a scientific projection, no matter how compelling, can itself sustain the influence of scientists in the long run, or even that it should.

At the onset of the pandemic, it was an epidemiological model from Imperial College London that was reputed to have triggered aggressive strategies against the virus in the UK, the US, and elsewhere. In the US, this model projected over 2 million deaths. Yet, at the same time, another model from the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation predicted 200,000 deaths. Faced with such uncertainty, the disparity between the models tipped policymakers towards the worst-case scenario.

Confronted with conflicting projections and driven by a sense of caution, the governments of most countries acted based on the worst-case scenario. Was this the best approach?

The waning influence of experts

Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been an effort to explain the policies implemented to confront the crisis, and to understand how science and scientific projections have informed these policies.

Expert projections held significant sway in Quebec, but this influence waned over time, despite the dire predictions they presented. During the early waves, high levels of uncertainty might have induced fear in both policymakers and the public, leading them to subscribe to the worst-case scenarios.

However, as the crisis persisted, some degree of fatalism took hold, inadvertently fueled by these very projections. Their credibility and influence gradually diminished, prompting decision-makers to drift away from scientific insights.

At the beginning of the pandemic, policymakers were guided by Quebec’s institute for excellence in health and social services (INESSS), a scientific organization commissioned by the government to provide projections on future hospitalizations.

Our research shows that, under constant conditions, INESSS’s projections led to stricter policies when they indicated that a significant increase in hospitalizations was anticipated.

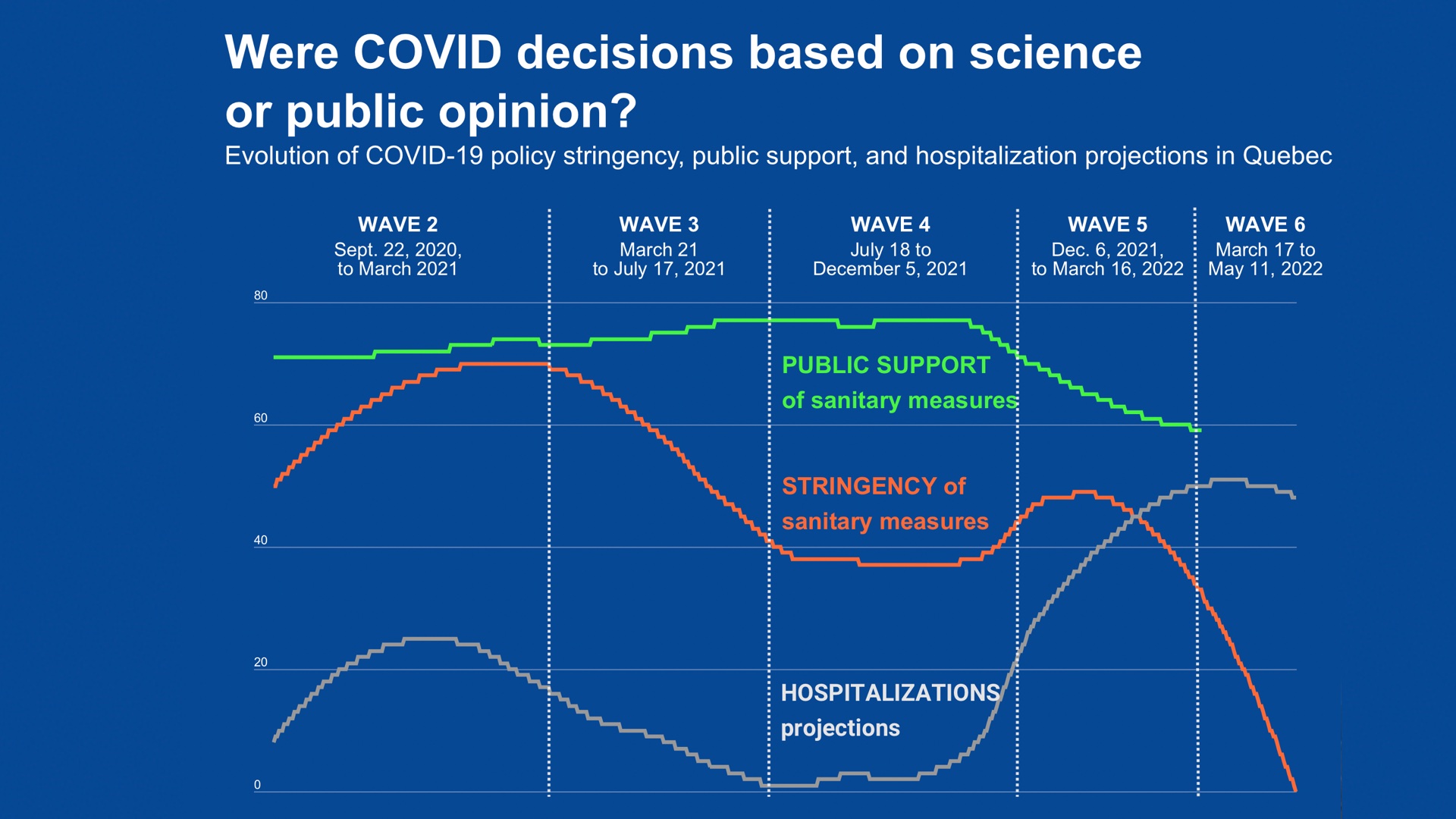

Figure 1 illustrates this clearly: during the second and fourth waves, the curve of the projections and that of policy stringency (based on an index developed by the IRPP) follow the same trajectory. Figure 1 also shows a very high public support for sanitary measures up until the fourth wave.

However, as the collective experience of the pandemic endured and vaccination rates increased, both the public and policymakers became inured to the dangers of the crisis. The more stringent measures that returned with each wave, such as the ban on public gatherings and the imposition of a curfew on two occasions, demanded significant sacrifices from the population.

Despite successful vaccination campaigns, successive waves of higher caseloads interspersed with the imposition of new measures diminished hope among the general public that each round of sacrifices would be the last, consequently reducing support for health measures.

The public’s fatalism presented policymakers with a dilemma as they formed their polices. Should they give more weight to the evidence and concerns of experts or to the public’s discontent?

Consequently, during the fifth wave marked by the emergence of the Omicron variant, projections from INESSS modelers lost their influence over policy stringency in Quebec. During this period, and for the first time in the entire pandemic, public support for restrictions dropped. The severity of measures to control the spread of infection declined right along with public opinion, despite particularly dire projections about hospitalizations.

When faced with highly concerned experts and growing public discontent, the government chose to respond to the latter. Figure 1 demonstrates this relationship between expert influence and public support.

Faced with uncertainty: science or emotions?

In our research, we also delved into the role of uncertainty and emotions in pandemic management. Most people expect crisis management to be grounded in rational choices informed by scientific evidence.

While we have demonstrated that public support weighed heavily during the pandemic, we also found that scientific projections were influential on the stringency of measures during the second, third and fourth waves. This is not to say all decisions during these waves were perfectly rational, nor that they followed scientific reasoning entirely free from emotions, especially amidst uncertainty.

An increase in stringency, spurred by alarming projections about hospitalizations, could also be fueled by negative sentiments – fear, for instance – pushing the severity of health measures to a level higher than necessary given available evidence.

We sought to ascertain whether policymakers were influenced by their emotions when confronted with dire projections, potentially prompting an exaggerated response.

Throughout the pandemic, Quebec decision-makers (primarily the premier, his health minister, and the head of public health) held press conferences regularly. In the initial months, they were daily.

We obtained transcripts of these press conferences. Using rigorous content analysis tools, we measured the references to scientific evidence, the communication of uncertainties, and negative emotions expressed by leaders.

Figure 2 demonstrates that the lower the level of scientific evidence, the stricter the measures were. It was also during periods when the provincial leaders expressed heightened negative emotions that they increased the stringency of public health measures. Paradoxically, a more detailed analysis allowed us to conclude that evidence had a greater impact on the severity of measures when leaders also expressed more uncertainty.

Evolution of COVID-19 policy stringency in Quebec, negative sentiments, sentiments of uncertainty and references to scientific evidence expressed by policymakers during press conferences.

Hence, it’s not necessarily the strength of evidence that drives policymakers to use them and communicate them to the public. Rather, during the pandemic, the stringency of policies appears to hinge equally on evidence as on the apprehension and caution triggered by the unknown.

Given these findings, it is impossible to conclude that scientific rationality prevailed, even during the first four waves of the pandemic.

Faced with alarming scientific projections, policymakers indeed ramped up the severity of measures, just as they relaxed them when the projections became more reassuring. However, public support was pivotal in determining the degree of stringency.

Moreover, stringency was as influenced by negative emotions and uncertainty as it was by hospitalization projections and scientific knowledge. Research has long shown that in uncertain contexts, emotions can be associated with overreactions by decision-makers. COVID-19 is no exception.

Also in this series :

Quebec’s lack of transparency during the pandemic was a mistake