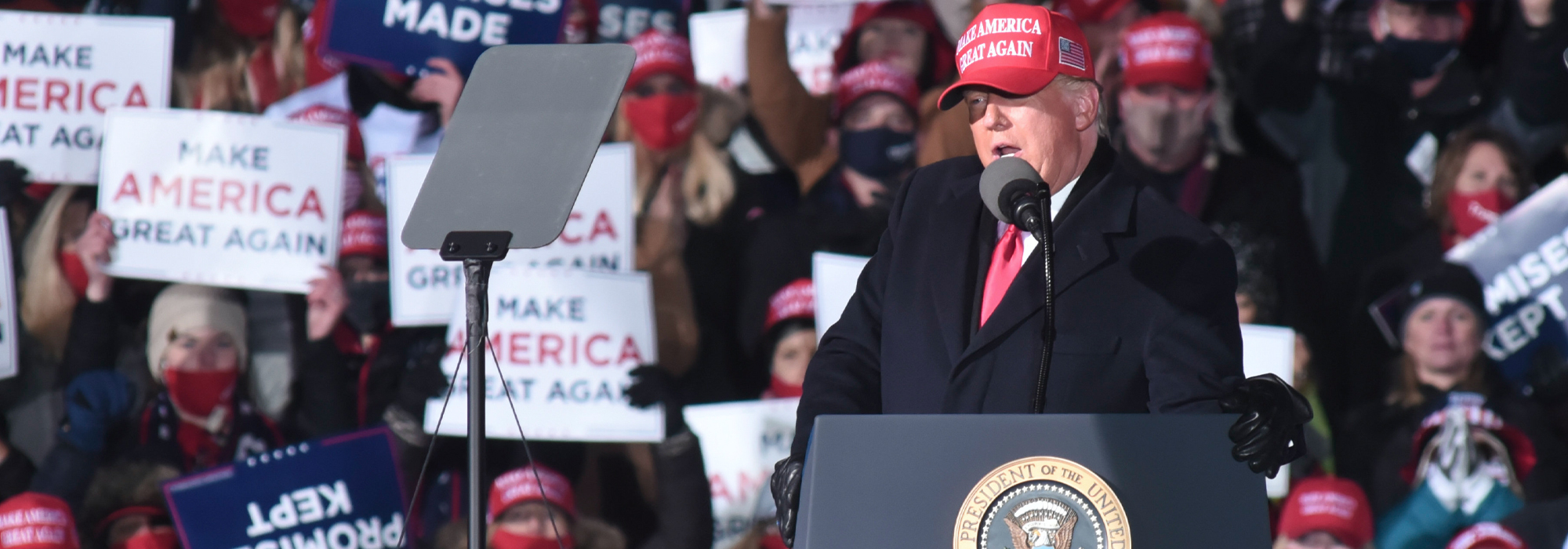

The sorry spectacle of the 2020 U.S. presidential election continued to play out Wednesday, with President Donald Trump falsely claiming that the election was a “fraud” even before all ballots had been counted. But this is par for the course, following a four-year campaign to weaken the legitimacy of America’s democratic institutions and processes. This should be a concern not only to Americans, but to all democracies, including our own.

Legitimacy refers to the moral authority of public decision-makers and processes. It helps to ensure that the decisions of duly constituted powers are accepted even by citizens who disagree with them. This is essential to civic life.

We tend to think of democratic legitimacy as the norm, but in fact only a modest minority of countries are fully functioning democracies. Max Weber, the early 20th-century sociologist, famously described three forms of legitimacy, the first two of which are essentially non-democratic: “traditional” (such as the Queen “by the grace of God”), “charismatic” (the sort exercised by cult-like figures such as Mussolini and Eva Peron), and “rational-legal,” which refers mainly to electoral democracies but could also include certain kinds of oligarchies, such as those that existed in 19th-century Britain. The relatively exceptional nature of democratic legitimacy makes its erosion in a benchmark democracy like the US a matter of global concern.

Democratic legitimacy in retreat

There are at least four ways in which legitimacy has been retreating in certain democracies, with the US taking an unhappy lead. The first is a slide toward populism, which leads toward charismatic rather than rational-legal legitimacy. The second is a decline in the stature and independence of public institutions. The third is the growth of a winner-take-all approach to the exercise of power, and a corresponding villainization of policy differences and political opponents. The fourth is the declining capacity of mainstream media to support civil discourse.

While all democratic leaders want to be popular, populism is a distinct beast. Populism equates what is popular with what is good, telling so-called ordinary citizens that their “common sense” values (including their biases) are more trustworthy than those of a supposed elite. Populists, no matter how privileged, present themselves as outsiders battling that elite. The more generalized and sinister the complaints against the “other,” and the more they include public institutions such as courts, legislatures, free media, or an independent public service, the closer they slide toward demagoguery. In its uglier variants, populism turns segments of the population against one another.

The attack on institutions

A demagogue will appeal to his or her supporters over the heads of public institutions in a way that violates long-respected conventions of public life. No institution is more central to democracy than the electoral process and no convention more fundamental than the peaceful transfer of power, yet astonishingly, as noted, we see that both have been called into question by President Donald Trump and his supporters.

When the demagogue begins to say that the “formalities” of the liberal state are a sham and that true democracy lies in the relationship between a leader and his or her people, we have left democratic, and even rational-legal, legitimacy behind in favour of charismatic rule.

Having been exposed to public scorn, institutions begin to lose their independence. Over time, powers of funding and appointment are used to put public organizations on short leashes and pursue agendas that undercut their historic and even statutory mandates. Appointments within the justice system become more pointedly political, and judicial or prosecutorial decision- makers become more discernibly responsive to the leadership’s preferred outcomes. Friends prosper at the hands of the system and opponents suffer.

The villainization of opponents and their policies

The third area of erosion is public discourse and the policy process. In a robust democracy, all players realize that the right to govern is rented, not owned. There is a give-and-take among competing policy positions, both through alternating terms in office and through negotiated compromises. But observers of American politics increasingly witness the near-criminalization of policy differences, along with the political opponents who espouse them. Parties are spoken of as if they are polar spheres of good and evil. Not only the mob, but the president himself calls for the prosecution and incarceration of opponents on the basis of nothing more than innuendo and conspiracy theories.

The expectation in a democracy is that ruling parties recognize that at some point the tables will be turned and that it is in everyone’s interest to make sure the rules are even-handed. But increasingly power is treated as an unmissable opportunity not only to change policies but to stack the rules of the game in one’s own favour for the future.

One consequence is growing dysfunction in policy-making. When the policy process is robust, most specific issues are more or less dealt with as they arise, and the threshold for overturning the work of an earlier government is generally high, limited to a few spheres of gut-wrenching intensity. In an atmosphere of conquest and obstructionism, compromise and inclusive policy-making are all but impossible. The result is a growing range of never-settled issues to be revisited endlessly as though the actions of the previous government were a kind of war crime demanding corrective struggle until one’s final breath.

The role of mainstream media

While much has been written about the failings of social media in supporting informed and civil discourse, the mainstream media face challenges of their own.

Traditional media have typically distinguished between reportage and punditry and seen their role as providing even-handed, objective reporting on political parties and actors. This has meant that candidates, no matter how extreme, are given equal time so that citizens can review both sides and make up their minds. But what if someone simply disregards the accepted norms of public discourse, including the requirement to adhere to something that can be rationally defended as truth? What happens when a candidate’s behaviour puts the electoral process itself at risk? Does the ethical requirement of neutrality extend to allowing such a figure to move the goal posts for normalcy and even rationality? In the US, while some media have gone partisan, most remain unsure of how to deal with such figures.

Another challenge for media is what can be called “narrative,” and the fact that language has implications beyond the moment. When media refer to a court decision as a victory for a political party, a narrative is created in which the legitimacy of the courts as independent, objective institutions is put at risk. Traditional media need to rethink how they frame issues and stories, and to weigh their impact on public perceptions of the legitimacy of public institutions and processes.

We don’t have ready solutions to most of the problems we have identified and certainly no panaceas. However, a useful point to note is the observation that legitimacy is closely connected to the concept of “voice” – the principle that all stakeholders should have an opportunity to be fairly heard and, where possible and within reason, accommodated. In a sense, this is the policy process’s equivalent of human and civil rights: it is one of those vital practices that separates majority rule from the mere exercise of raw power. This will only happen if the US political class realizes that the country is on the brink. As matters stand now, that seems unlikely. No matter what the outcome of the election, the polarization looks deeper than ever.