It’s been five years since the Canadian government legalized and regulated non-medical cannabis cultivation, commerce, and consumption. California is ahead of us by two years, having followed a similar experiment in 2016 when it legalized recreational cannabis. It was the first U.S. state to legalize medical cannabis access in 1996.

Today, California and Canada are facing similar challenges though they have adopted vastly different regulations. The two jurisdictions offer an interesting contrast in how regulatory frameworks can support or undermine a nascent legal cannabis industry.

Much has been said about the aims of legalization and whether it should draw on the business model for alcohol, with its heavy industry marketing, or that of tobacco, which has been subject to a more recent public health focus. Canadian cannabis has followed a bit of both.

Federal legislation created Canada’s cannabis markets, with retail regulations developed and implemented largely at the provincial level. Importantly, this transparency provides a degree of stability that is not currently present in the United States. It allows the Canadian cannabis industry to plan for its future. But Canada’s cross-border banks remain skittish about financing the sector for fear of violating the ongoing U.S. prohibition on cannabis.

Evidence from the past five years suggests that the regulations have failed to provide equitable access to the industry and develop balanced tax structures. Legalization in Canada and California also remains hampered by the legacy of global cannabis prohibition.

California

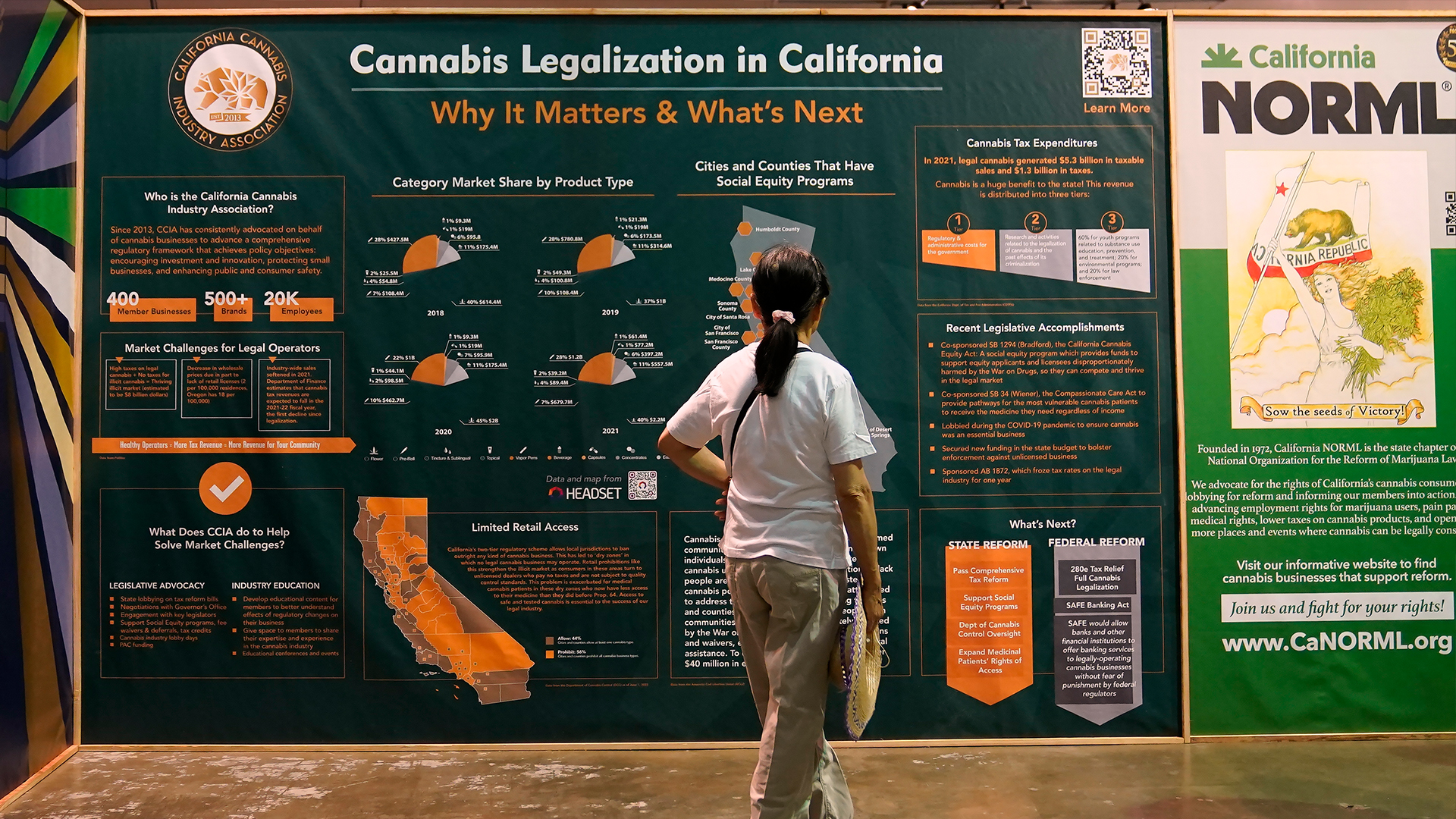

In California, like in other U.S. states that have legalized cannabis, the cannabis industry operates in a legal grey area, entangled with federal prohibition. At a minimum, cannabis needs to be reclassified from Schedule 1 (the category for heroin and LSD) to Schedule 3, as recently recommended by the Biden administration.

That is crucial because otherwise banks and credit unions face federal prosecution and penalties for providing financial services to the cannabis industry. This is despite over a decade of congressional movement to pass the Secure and Fair Enforcement (SAFE) Banking Act, which just recently moved out of committee and will be taken up by the full Senate.

In California, licensing fees, environmental compliance requirements, high taxes and local resistance to commercial cannabis have sustained an illicit market. Drug-war tactics persist with increased law enforcement funding, ongoing racial disparities in arrest rates and no-knock inspections of licensed growers.

A cultivation tax was initially imposed by the California Department of Cannabis Control on each ounce produced. That stopped on July 1, 2022, but a 15-per-cent state excise tax remains at the point of sale, in addition to local taxes levied. These additional taxes make legal cannabis more costly than what is produced illegally.

A course-correction on cannabis equity: the moment is now

When California adopted Proposition 64, legalizing adult use of cannabis in 2016, local jurisdictions had the power to ban cannabis businesses. Most did. In fact, 61 per cent of California cities and counties prohibit cannabis retail. Consequently, there is more cannabis grown in California than can be sold in the existing retail market.

Beyond the retail crunch, intensive lobbying by large-scale cannabis cultivators created a loophole in the regulations, permitting individuals to hold unlimited small-scale licenses. This has resulted in concentrated ownership of these “stacked” cultivation licenses in places like Santa Barbara County, where five individuals own 50 per cent of the 980 licenses. This concentrated ownership provides market control that undercuts smaller craft cultivators with historically significant ties to the communities in which they live and farm.

As of the end of 2022, there were 10,712 active cultivation licenses in California representing the cultivation potential of 2,693 acres (or 6.9 million square metres) – far more than in Canada – with limited retail distribution options statewide.

Canada

Canada faces similar issues with regulating cannabis. Prime Minister Trudeau’s Liberal Party has legalized cannabis but treats it like a far more dangerous substance than even tobacco.

Excise taxes are high. There are strict production and transportation requirements and tough maximum sentences for minor offences (such as 14 years for providing cannabis to a minor). Delays in opening retail stores reduced access to legal cannabis. All of it has slowed the conversion of people away from the illicit market.

Many Canadian municipalities have banned cannabis retail. In Ontario, about one in 10 municipalities blocked access to cannabis retail stores. These municipalities tend to have higher concentrations of conservative, older, white populations compared with other municipalities across the province.

The high initial prices have come down, excise tax payment schedules have been restructured and the vast majority of consumers purchase from legal retailers now. But high production costs and the lower retail prices have left the industry in a difficult situation, and many companies remain unprofitable.

There’s also a lack of diversity in leadership positions and Indigenous communities’ rights have not been sufficiently addressed in cannabis legislation. Meanwhile, there has been little effort by government to undo the harms that prohibition caused, particularly against racialized communities.

Even with strict regulations, Canadian legalization was set up to commodify cannabis, and it has succeeded in that regard.

There are only about 957 federally licensed cannabis producers and processors in Canada, and at their peak they had more than 2.2 million square metres of indoor cannabis growing space. In an effort to grab market share, these companies grew so much cannabis that Canada has a surplus of 1.5 billion grams of cannabis sitting unsold in warehouses.

From the start, Canadian cannabis regulations required immense capital to launch a cannabis business, which favoured large corporations but precluded access to the market for many people involved in the legacy market. The use of provincially owned wholesalers has also made entering the market difficult for smaller players. The people most impacted by the drug war have had the least ability to enter the regulated market as owners and operators. It’s a sign of the failure to institute policies to undo the harms brought about by a century of cannabis prohibition.

A past cannabis conviction doesn’t automatically disqualify someone from a Health Canada security clearance, but other past convictions do make it harder for anyone from disproportionately policed communities to gain clearance.

Access

Consumer access to cannabis is a key component of pulling people away from the illicit market. But since most California jurisdictions have banned retail, there are only about 1,200 active licenses plus 485 licenses for delivery.

The retail density rate is 3.5 dispensaries for every 100,000 California residents, though it varies enormously statewide. In the fabled “Emerald Triangle,” three northern California counties known for their abundant cannabis output, there are 19.1 dispensaries per 100,000 residents. In politically conservative Kern County, northwest of L.A., however, there are only two dispensaries available to a population of 916,108 people. Compared with Canada, California has far fewer retail options.

Provinces and territories regulate most aspects of retail licensing and policy in Canada, and no federal data exists for the number of retail stores. The best estimate as of August 2023 is 3,800 retail stores in Canada, a rate of 9.7 retailers per 100,000 residents.

This varies between provinces, with Ontario at 11.4 retailers per 100,000 residents, and Quebec at 1.1 per 100,000. By our calculations, there are only about 2,400 Canadian cannabis consumers per legal retail store in Canada. Some believe this is far too many stores, and the overcapacity is hurting the industry.

Conclusion

Canada’s fifth anniversary of legalization provides evidence for the need to implement significant changes both in Canada and the United States.

First, regulated cannabis won’t be successful anywhere until cannabis is removed from the U.S. list of prohibited drugs for non-medical purposes in the 1961 Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs. Prohibition continues to hurt the U.S. cannabis market, restricting access to financial services and global markets.

Second, in both countries, social equity must be prioritized to reduce the costs of entry, especially for communities disproportionately impacted by cannabis prohibition. There is no room for justice if the sole focus is the profitability of the industry and how much tax revenue it will generate.

Third, the tax structure must be recalibrated in both countries to more closely align with other agricultural and alternative medicine industries. Cannabis tax revenue cannot fill coffers if punitive sin-tax policies drive away consumers and hamper the industry.

Production and retail challenges won’t be solved solely by creating more business-friendly regulations. It is worth considering non-profit production/retail models that more closely align with consumers’ values, and replicate the illicit compassion clubs that provided cannabis and community prior to legalization.

Taken together, these policy changes would help create an economically viable and socially just cannabis industry that promotes well-being for the millions of Canadians and Californians who consume the plant and benefits the communities in which they live.