Like several billion other people, I awoke the day after the US election trying to make sense of the election of Donald Trump as the leader of Canada’s powerful southern neighbour. Even at a time of severe economic anxiety, why did 59 million Americans choose a candidate who has so deeply divided the nation?

The first post I saw that day — an early morning essay by New Yorker editor David Remnick — is required reading for every person of conscience. He notes: “Trump was not elected on a platform of decency, fairness, moderation, compromise and the rule of law; he was elected, in the main, on a platform of resentment. Fascism is not our future — it cannot be; we cannot allow it to be so — but this is surely the way fascism can begin.”

Reading this moved me from despair to determination. Those who believe in these values, which Trump rejected, need to understand what happened — to fight it, to stop it and to prevent it from happening again.

A victory of communication

That is why we must understand Trump’s election as a victory of communication. No, not of the ethical variety championed by the world’s public relations professional associations, but a dark art of deception and distortion, one that skilfully exploits the weaknesses of the 21st century media landscape.

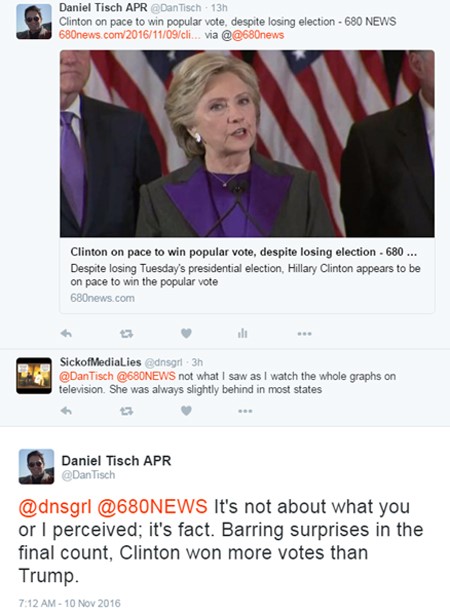

Despite being the oldest person ever elected United States president, Trump was born for the social media age. He intuitively understands the power of disintermediation that allowed him to speak directly to a vast audience, dutifully amplified by the mass media. He subtly signals the dark extremes of society, while understanding that mainstream citizens live in filter bubbles, in which we each choose our own news and, dangerously, our own facts. Here’s a typical exchange I experienced (note the user’s ironic Twitter name):

Let’s look at the six most dangerous strategies and tactics in the Trump playbook.

1. Gaslighting

Gaslighting is a form of psychological abuse in which a victim is manipulated into doubting their own memory, perception, and sanity. Here is how the Washington Post’s Ben Terris applies it to the election:

Reporters and political junkies experienced this in a collective way during the vice-presidential debate in October, when Gov. Mike Pence (R-Ind.), Trump’s running mate, shook his head “no” to the charge that Trump had praised Vladimir Putin. He denied that Trump had suggested more nations get nuclear weapons, that Trump had proposed a “deportation force” to go after undocumented immigrants, and that Trump wanted to punish women for having abortions.

Never mind that the political press, along with many others, had watched the Republican nominee say all these things in the preceding weeks and months, and it was all on tape. Trump’s running mate used “polish and confidence,” wrote Jamelle Bouie in Slate, “to deny Trump’s rhetoric and behavior and gaslight the country that has borne witness to them.”

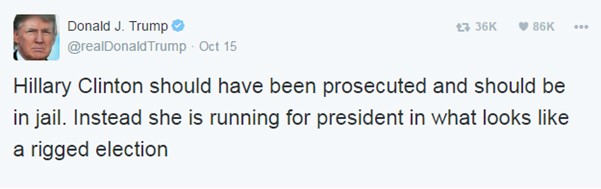

2. Defamation

The level of defamation in this election was shocking. Trump excelled at it, persuading millions of Americans that Clinton had committed a crime, despite the absence of credible evidence or charges, let alone proof. He knew that his opponent was unlikely to resort to legal channels, which move too slowly for the internet age and would risk keeping the allegations in the news.

3. “Otherization”

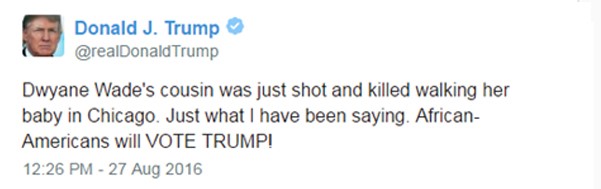

This is a favourite of many demagogues — from 20th century fascists and communists to 21st century authoritarian populists — blame an “other’” for an economic or social ill. Trump was fond of this strategy, as he targeted African Americans, Latinos, Muslims and women, to list but a few.

Many of Trump’s comments in this vein were overt, such as those demeaning women and branding Mexican immigrants as rapists and Muslims as terrorists. Others were covert — so-called dog-whistle politics. Some were perhaps subconscious.

Many dismissed Trump’s darkly brilliant slogan “Make America Great Again” as a typically laughable con job. But for many white men lacking education and prospects, it called to mind a comforting past — one that was anything but great for minorities. At other times, Trump’s social posts revealed his innate bigotry:

4. Media intimidation

A power user of Twitter, Trump took full advantage of the reality that in the social media, to quote David Remnick, “articles in the traditional fact-based press look the same as articles from the conspiratorial alt-right media.”

Trump’s relentless narrative about the “rigged media” was chillingly effective. He roused his supporters to near-violence against reporters at rallies, and then looked the other way as White supremacist groups targeted reporters and their families with horrifying threats.

Trump’s rigged media narrative also forced editors and reporters everywhere to bend over backwards and show balance. The result: no topic in the election received more attention than Hillary Clinton’s use of a private e-mail server when she was secretary of state — a minor transgression by any objective measure when compared with Trump’s misbehaviour.

5. Lack of transparency

I once thought no one could get elected to the American presidency without revealing his or her tax returns, to confirm their bona fides and to avoid conflicts of interest. I was wrong. Voters let Trump off the hook entirely in this regard, and he managed to get through the campaign without meeting this basic test of transparency.

The one blessing in the social media age is that transparency is sometimes forced upon a newsmaker, as Trump discovered at the low point of his campaign — the release of the Access Hollywood video in which he bragged about sexually assaulting women. And that brings us to…

6. The fake apology

Trump is not known for admitting errors, let alone apologizing. The release of the video of his shocking comments about women forced him to apologize. His first words reminded me of former Toronto mayor Rob Ford’s, when he said: “I never said I’m a perfect person…” (as if that was the standard to which he was being held).

In the video, having said just enough to generate headlines stating he had apologized, Trump segues into attacks on Hillary and Bill Clinton. The effect is to nullify the apology entirely. After all, rancour is not remorse, and apologies should not be attacks. This type of non-apology actually compounds the wrong-doing. It prevents restoration and halts healing.

A democratic imperative

Here are the questions we must ask: How could this happen? How can we stop it from happening again?

In a speech on the evening before the election, President Barack Obama noted that the social media “magnifies our divisions and muddies up the facts.” As the politician who pioneered the use of the social media as a campaign tool in 2008, Obama understands the its virtues — and its dangers.

“A week is a long time in politics.” This adage predates social media — in today’s age of information overload, of short memories and attention spans, of transient celebrity and instant gratification, a week is an eternity. The disgraced candidate of October becomes the victor of November.

In these times vigilance is required more than ever before, and this is not easy for voters, who are often complacent about the durability of their democracy and unaware of the fragility of their freedoms.

I hope Trump confounds expectations and unifies the nation. Regardless of what happens during the Trump presidency, however, the lessons from this campaign are grim but clear: only when we understand how communication can be used for division can we aspire to see it used for hope, healing and harmony.

Photo: a katz / Shutterstock.com

This article is part of The US Presidential Election special feature.

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.