(Version française disponible ici)

The ascension of King Charles III has predictably revived the question of Canada’s ties with the monarchy. Quebec’s National Assembly just adopted a bill making the oath of allegiance to the Crown non-compulsory for members. Whatever the outcome of Quebec’s gesture, Canada is not about to cut its (constitutional) tie to the British monarchy. However, at some point in the future, Canada will undoubtedly wish to give itself a head of state who is not a foreign sovereign. But replace the British monarch with what?

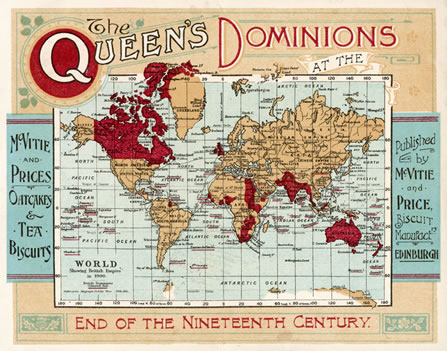

Constitutional complications aside – any change would require the approval of all provinces – Canada is caught in a conundrum. Ties to the British Crown have strong historical roots, far stronger than in the other Old Dominions (Australia and New Zealand). As well, the simple republican solution – replacing the Governor General with a president, as countries such as Ireland, India and more recently Barbados have done – is not (except in Quebec) a politically palatable option for the same reason. So, we do what? We don’t want a republic but would like a Canadian head of state. A classic catch-22.

I propose a possible solution, which many readers will undoubtedly judge off-the-wall. But the only way of knowing that is by putting it forward. I shall begin by explaining the reason for keeping a monarchal (non-presidential) model. A caveat here: most francophones (and probably many others as well) would gladly accept a Canadian republic. But English Canada, and many others as well, will continue to eschew a republic.

The virtues of constitutional monarchy

It is not entirely an accident that some of the most stable democracies in the world, not just Britain, have chosen to remain constitutional monarchies. The three Scandinavian kingdoms are obvious examples. There are several reasons, but the most important is the separation between the head of state (the monarch in these cases) and the head of government (the prime minister). Nation and government are separate. A fundamental error of the American (non-parliamentary) presidential system was merging the two. The president, directly elected, comes to personify the nation, a primary reason why almost all nations that have adopted the U.S. model, as did most countries in Latin America, have at one point or another fallen victim to authoritarian leaders.

The monarch, in the parliamentary model, personifies the nation, providing continuity above politics (above the prime minster), as governments come and go. The nation can choose, as noted above, to replace the monarch with a president (nomination procedures vary). But a president rarely commands the affection of a monarch, nor is his or her status above politics as clear-cut. However, the reasons why Canada continues to eschew the Irish or Barbadian route run deeper.

Moving on from the monarchy incrementally

What would Canadian politics look like without a Queen or King?

Very simply, English Canada was founded in opposition to a republic. Loyalty to the Crown was the guiding light of those who fled the American Revolution to come to what was to become Canada. Here, in this remaining British possession in North America, they would build a properly governed colony, respectful of tradition, the Crown and the associated adjective “royal” – proudly proclaiming their difference from the brash American republic to the south. As such, abandoning the visible symbols of monarchy, not least the adjective “royal,” is tantamount to a betrayal of the founding principle of Canada as a distinct nation in North America. How can Canada be a republic if its very raison d’être was not to be? In this, Canada is different from Australia or New Zealand – the perpetuation of monarchy not being a driving motivation of their first settlers. Australia was founded as a penal colony, settled by convicts, many Irish, with obviously little love for the Crown.

Returning to Canada. The challenge: imagine a model that would allow the nation to preserve the advantages of constitutional monarchy – a head of state above politics – and retain the adjective “royal” (symbols matter), allowing the RCMP to keep its “R,” but a model that would also find favour with Canada’s less monarchal-inclined population.

Chief and head of State

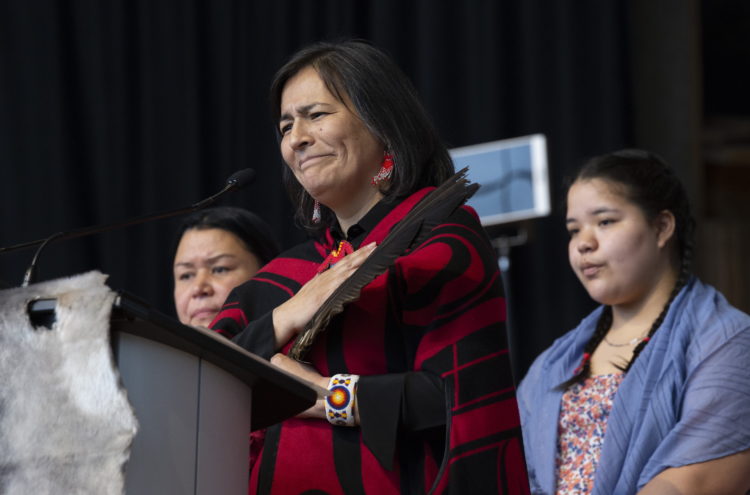

Mary Simon, Canada’s first Indigenous Governor General, has helped by setting the stage, although as a role model I would have much preferred that she be able to speak French in addition to English and her native Inuktitut. I suggest that all future heads of state of Canada be Indigenous. That is Step 1.

Step 2: Canada ends its formal tie to the British Crown, with the current vice-regal representative being replaced by a new Canadian office with a corresponding title: chief and head of state (cheffe d’état du Canada). I have used the feminine in French for a reason.

The important word here is “chief,” which is where a little linguistic imagination is called for – of which Canadians (certainly lawyers) are surely capable, given the political will. The title “chief” would henceforth have the same interpretive meaning, by act of Parliament, as monarch: i.e., king or queen. This is not as absurd as it sounds. Most European monarchs were descendants of Celtic or Germanic tribal chiefs. Many readers will know the old saw: “what’s the difference between a language and a patois? Answer: a language is a patois with an army.” Mutatis mutandis, historically, a king or queen is simply a tribal chief with an army (who defeated other chiefs). Canada’s chief, as heads of state elsewhere, would be the ceremonial commander of the armed forces. The same act of Parliament would stipulate that federal and provincial institutions retain the prerogative of using the prefix “royal.”

I propose an elective (not hereditary) monarchy, which again is not terribly original. Many of the kings (and sometimes queens) of the ancient world and Europe were elected by councils of nobles – Holy Roman emperors among the better-known examples. Canada’s originality here is in the title “chief,” in deference to its First Nations. For the nomination process, I would stay close to current practice, although this would need to be codified: a non-partisan advisory council, such as former prime minister Stephen Harper’s advisory committee on vice-regal appointments introduced in 2012, which has since fallen into disuse but remains a useful precedent. I shall not comment on the council’s composition. The important point is to avoid a popularly elected head of state, which risks politicizing the office. Canada’s chief must be seen as non-partisan, above politics.

Eligibility criteria, aside from the usual (minimum age, education etc.), would include two requirements, plus a preference:

1. Indigenous, First Nation: The main contentious issue I see is the inclusion of Métis. I would tend to be generous.

2. Trilingual: English, French and a relevant Indigenous language, with wiggle room on the latter, depending on the language’s use in the community. This, hopefully, would act as a clear signal that the survival of Indigenous languages is a national priority.

3. Female (preference criteria): I would be inclined to limit the office to women, but that is probably pushing political correctness too far.

The recent nominations of Michèle Audette to the Senate and of Michelle O’Bonsawin to the Supreme Court (both trilingual) suggest that good candidates would not be lacking.

On tenure, I favour long term limits, perhaps seven years, renewable, to give the office the stability it requires. This raises the question of accountability, which remains unresolved under the current system, probably because we have never given the office much thought. To my knowledge, no Governor General has ever been formally dismissed; only asked (by the PM) to resign, as recently happened to Julie Payette. This would, of course, no longer work for an office that is in principle above the prime minister. Here, the rules governing the removal (impeachment) of presidents in parliamentary republics (such as Ireland and Germany) might act as useful guides, often requiring a substantial parliamentary majority and subsequent assent of the Supreme Court.

I cannot end this (modest) proposal without returning to the ties to the British Crown, which many will be loath to relinquish. The formal ties will necessarily be broken. However, I see two possible avenues for compromise. First, the chief’s oath of office might include a phrase on the duty to protect and uphold (or something to that effect) the democratic legacy bequeathed Canada by the British Crown. The operative word here is “democratic.”

Monarchy’s rights, privileges and symbols in Canada can be changed

An empowered GG could restore Crown’s role as Treaty partner

Second, the regal link will also need to be replaced for lieutenant-governors. Why not leave the provinces free, henceforth, to choose the title and form of their provincial head of state? This should please Quebec, which could adopt a title, with appropriate ceremony, consistent with its conception of itself as a nation. By the same token, provinces that so wish could reaffirm their historical attachment to the British Crown via the symbols and ceremony surrounding the office while nevertheless staying short of a formal pledge of fealty. Nothing prevents provinces from displaying visible symbols of their heritage – British, French or other.

It’s not useful to muse further on what an elective Canadian monarchy might entail. My goal here is simply to throw out the idea of a Canadian head of state who, while untethered from London, would nonetheless allow Canada to keep the accoutrements of monarchy and finally give Canada’s first inhabitants the place they deserve in its constitutional firmament. Why not also count on our Indigenous Peoples to give the office the pomp and ceremony it deserves? Who knows, the idea might catch on. Why not a Māori monarch for New Zealand and an Aboriginal one for Australia?