Elections are rarely exercises in exorcism. But two political ghosts repeatedly hauled out to frighten voters and small children were finally banished by Ontario voters. The Liberals tried one more time to brandish the threat of a Mike Harris redux but dropped it early on as voters were no longer frightened by a premier retired more than a decade ago. The Conservatives eventually dropped their anti-Bob Rae rhetoric as NDP Leader Andrea Horwath was clearly not him, and, as she pointed out with a wry smile, he was leader of another party today.

Elections are normally exercises in democratic choice.

With only 49 percent of Ontarians voting, a recordlow turnout, the other 51 percent said, “None of the above.” Disengagement was the order of the day. This unprecedented abstention raises several unpleasant issues for the government, for all the political elites and for the future. With fewer than one out of four voters choosing the governing Liberals, as they head into what could be another recession and face some very tough choices about whose services to cut first, it is not the sort of mandate elections usually deliver.

To ensure the message was not lost, voters denied Premier McGuinty a majority; he is the first premier in a quarter century to receive such a slap. True, he fell short by only one seat, but as Conservatives and New Democrats observed, a shift of fewer than 5,000 votes in the right places would have seen him defeated.

The Ontario economy has never really recovered from the 2008 recession. It was kept on life support by a combination of American, Ontario and federal government stimulus spending until the summer of this year. At a cost of 500,000 jobs lost and more than $52 billion of new provincial debt in the last three years, not to mention the federal stimulus program and the auto bailouts, the battle against a structural decline in Canada’s largest economy and export engine was very expensive. Some economists believe that merely to avoid another round of layoffs and factory closings, another round of stimulus, pushing debt and deficits higher once more, will be required this winter.

When first Europe and then the United States started to go wobbly this summer, Ontario’s export-led economy was sure to follow. By the day the writ was dropped, just after Labour Day, there were warning signs from some economists that Canada could not resist the double whammy of a decline in the US and shaky European markets. By the night of the one real leaders’ debate, three weeks later, deep concern was the order of the day in stock markets, finance ministries and central banks across the developed world. Voters conveyed their worries to thousands of party canvassers across the province with mounting anxiety and even anger.

This dramatic change in voter expectation and anxiety was slow to move the party strategists. It was not until the debate week that the parties began to reshape their messaging to reflect the prospect of a potentially grim winter ahead. Andrea Horwath predictably and wisely, given her base, focused on those who would be most severely hit by another winter of layoffs. The McGuinty campaign stole a page from the Harper playbook and pleaded for a majority under proven leadership. Improbably, and foolishly, the Hudak campaign stuck to its anti-tax message, not understanding that voters afraid of being laid off worry more about getting paid than paying taxes.

For the McGuinty government, the experience of an earlier regime suffering a sudden hole appearing in the economy may be instructive. Bob Rae’s unexpected and unprepared government faced an even harsher political nightmare in September 1990, taking office on the cusp of the deep recession of 1990-91. The despair that engulfed the province by mid-winter 1991 had been only a shadow on the horizon during his campaign. Rae could not claim to have inherited the hole in the Ontario economy from the defeated Liberal government before him, though he tried. It grew so quickly that an alleged budget surplus in the spring had become a billion-dollar political boat anchor by fall. (Disclosure: By then I was helping to sell the province’s debt as Ontario’s senior Asia trade diplomat.)

Like David Peterson waltzing to defeat in a similarly sunny summer campaign, Dalton McGuinty whistled vigorously past the economic graveyard from the campaign’s beginning until almost too late. Curiously, he adopted the pose of a premier who had vanquished the recession, bragging about classrooms, waiting rooms and factory jobs delivered during his second term. His campaign bus, plastered in a word cloud of boasts and statistics, was quickly dubbed the “bragging bus” by critics. The party’s flagship TV ads were of Premier Dad standing alone on screen quietly boasting of his achievements.

Andrea Horwath predictably and wisely, given her base, focused on those who would be most severely hit by another winter of layoffs. The McGuinty campaign stole a page from the Harper playbook and pleaded for a majority under proven leadership. Improbably, and foolishly, the Hudak campaign stuck to its antitax message, not understanding that voters afraid of being laid off worry more about getting paid than paying taxes.

It was a strangely tone-deaf approach for a government seeking a third term at the tail end of one gruesome recession, while visibly teetering on the edge of a double dip. For those who believe it is rarely their enemies but Liberals’ own arrogance in power that most often defeats them, this almost became a textbook case. A more thoughtful campaign team would have begun with an expression of chagrin at the pain of the recession and its impact on their ability to deliver. A more self-aware premier would have dialed it back a few notches.

Several ministers and influential Liberals pleaded with the Liberal war room to insert some humble pie in the Premier’s message, to no avail. As one said privately, “For Chrissake! We didn’t create the recession, we don’t have to apologize that it made it impossible for us to do things we wanted to do! We’d look better if we ‘felt their pain’ before telling voters how great we had been.” Ontario voters are traditionally unimpressed by braggadocio, and Dalton’s “humble father” stance probably saved him from a more punishing election night result, given the gap between the government’s claims and the bleaker reality experienced by many Ontarians.

But what definitively saved them from real electoral humiliation was the astonishing naiveté of the Hudak campaign team. Conservatives in Canada and around the world carry the burden of being seen as the party of “angry old white guys.” The federal Conservatives, in less than a decade, have done an astonishing job of erasing that deeply ingrained perception. Like social democrats’ vulnerability to charges that they “couldn’t run a peanut stand,” conservatives must always be cautious not to open their vulnerability to charges that women, gays, the young and brownskinned Canadians are not part of their coalition.

In this respect, Hudak and his campaign team could not have been more foolish.

First they attacked a proposed Liberal program designed to help “foreign workers,” as Hudak called them. It was indeed a curious plank to put in the campaign window: costed at less than $20 million it would have done little; targeted at less than a thousand workers a year, it would have benefitted few. Some wags dubbed it “Jobs for Foreign Ph.D. Cabbies.” By piling on so vehemently against it, however, Hudak reinforced the suspicion among many Ontarians that in contrast to the Liberals’ “Forward Together” message, Tories did not include some groups in their vision of the province’s future.

There was an approach to whacking the Liberals’ cynically divisive politics that one could have imagined a more adroit campaign team delivering. If the Tory messaging had been to attack the Liberals for creating division, to champion their own plan for immigrant integration, the damage would have been contained. If they had campaigned on the “One Ontario” theme that the Liberals had used against them four years earlier, Hudak might have been premier.

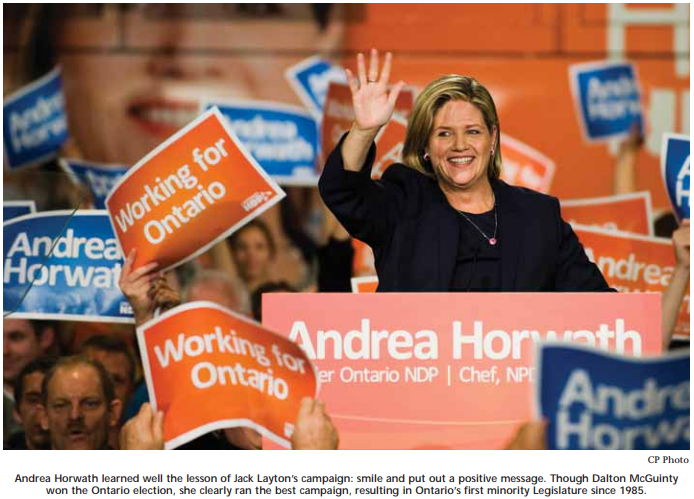

Meanwhile the foolishness of the two larger parties gave NDP Leader Andrea Horwath her first campaign traction. She was able to dismiss each competitor’s attempt at a “Southern strategy” style of American politics, positioning herself as a different kind of politician.

Television debates have come a long way since the days when a sweaty upper lip or a good one-liner could end a career. Today they are the centrepiece of modern electoral politics in almost all of the established democracies. Even the United Kingdom which, perhaps typically, had resisted them for nearly half a century finally succumbed. Arguably, David Cameron and Nick Clegg govern Britain today on the strength of their debate performances.

Much of the media pundit class has failed to keep up with what makes debates important in the eyes of voters. They still tend to score them like a basketball game or a contest between teens on a high school debating stage, rewarding points for style and wit and form. Those are not the tests that voters bring to the contests. In campaign after campaign, good qualitative researchers have demonstrated that debates are not about zingers but about character.

They are the only moment in the life of a campaign when voters, peering through the camera lens, get a glimpse of a leader’s soul. They see the quality of leadership under stress. They spot the truth, or the attempt to conceal it, in the frightened glances that every other event in modern politics does its best to distort, exaggerate or prevent.

It is the moment when two guys in a bar turn to each other and say, “Glass jaw, eh?” as happened to Michael Ignatieff. He simply looked pole-axed when Jack Layton thundered at his chronic absenteeism during the English-language federal leaders’ debate last April. It is the moment when a husband turns to his wife and says, “I know he’s smart, and he’s good at this stuff, but I just don’t trust him.”

It is because the risks and rewards are so high that smart campaign strategists do not allow the final debate to be too close to election day. It’s not possible to recover in time from a bad performance. Liberal and Conservative strategists were already muttering, “Never again!” after this campaign’s single debate, which the broadcasters had pushed back to the final nine days of the election.

On the strength of his debate performance, Dalton McGuinty seemed not to have understood what voters would judge as a win. Usually experience tells in debate contests. The first time you leap without a safety net into a competition in front of hundreds of thousands of people, whether as an Olympic athlete or a political debater it is not likely to be a polished, confident performance. You won’t be cool under attack, or capable of sliding the knife in with a smile. Curiously, McGuinty was worse in this debate than in his previous rounds.

Like an over-confident high school best boy, he exploded into living rooms waving his hands, blathering statistics, with a silly grin that made one wonder what his handlers had pumped him with in the green room. The rapid-fire recitation of hospitals, schools, highway miles and minutes of recovered wait times was almost Pythonesque. If you closed your eyes you could almost be listening to a Soviet era, five-year-plan speech on the “Economic Achievements of the People.” As both his opponents pointed out, again and again, it was a curiously tone-deaf stance to offer to a province with more than half a million unemployed voters.

Hudak did better, but he suffered in the authenticity stakes as well. He restrained his robotic attack impulse and avoided the nasty edge that his voice takes on when in that mode. He was compelling about the failures in the long run of the McGuinty government and scored the sound bite of the night when he told McGuinty: “With respect, sir, nobody believes you anymore.” Hudak was less effective on his vision of a better future. He, like his campaign strategists, seemed to believe that his message about tax cuts leading to job creation would be compelling without offering even broad hints about how this legerdemain would actually deliver. His opponents and the media were rough on this gap on the night and later. In a curiously revealing insight into his own discomfort with how his handlers were forcing him to perform, asked to rate his own performance later, he laughed and said he had been a little “too unscripted” and should have stayed on message better.

Horwath should not have done as well as she did, being a newcomer both to debates and to leadership. Her handlers were spooked when she delivered a wooden and clumsy performance only a few days earlier in a one-on-one debate with Hudak in Northern Ontario. Improbably, as if to demonstrate how arrogant and Toronto-centric the McGuinty government had become, he refused to join them for the debate in Thunder Bay. Hudak and Horwath dropped regular sarcastic references to his absence in the TV debate. “We missed you in Thunder Bay,” she said with a killer smile. Northern voters punished the slight on election night.

Unwisely, Horwath used her son’s experience with a hospital waiting room as an example of the failures of the health care system. It seemed forced on the night and several times later she had to clarify what actually happened. Similarly, Hudak used his daughter’s painful medical battles for political gain that night, and many parents and voters winced. McGuinty, who sometimes offers bizarrely detailed updates on his family life, was more appropriately reticent. He made up for it on election night in a maudlin speech that singled out every family member, staff person and colleague for special thanks.

The NDP Leader is an unusual woman politician, neither Thatcherite in her adoption of a gender-bending masculine stance, nor Palinesque with flirtatious riffs for the guys in the front row. Her comfort zone is clearly feminine — a mother, a proud daughter and a self-confident woman — but her winning smile conceals an edge and a spine that is now acknowledged by erstwhile opponents in the party and now in the media. She used, unfairly, the hesitation of three men, including the moderator, sharing a stage with one woman to sneak shots in at her opponents, and to undermine their performances with quick jabs. TVO’s Steve Paikin, Canada’s debate moderator extraordinaire, was slow to discipline her pushing the boundaries.

Enragingly to her opponents, she also slid over policy gaps and even made a couple of curious bloopers — she described Samsung as a “publicly owned company” which would come as a surprise to its shareholders — that no one noticed. Several times, each of her opponents froze, mid-sentence, mum in their fear of appearing to pick on a woman, even as she attacked them. Her position on camera between her two opponents gave her great positioning on TV. She merely had to hold her arms wide as if to say, “Boys, Ontario expects better!”

In politics, it is not usually an advantage to be the newcomer, a woman and the pollsters’ choice as weakest competitor. The licence, the light scrutiny and the room Horwath was granted by her opponents was, perhaps, the exception that proves the rule.

She did not give much of a glimpse of the detail of an NDP government, and critics complained that of the three she looked the least like a premier. Her team chuckled at the sniping, confident that she had done what she needed to do: look like she belonged on that stage, and that under pressure she was a competent and confident performer. Three polls in rapid succession confirmed their confidence, as Horwath’s profile and approval slowly lifted in the campaign’s final days.

The campaign’s closing days were anti-climactic as the three campaigns attempted to solidify their positions. The New Democrats continued to pound their “who will fight for you message” with confidence and a leader who not only did not stumble but visibly grew in confidence. Horwath’s final rallies were large and boisterous, while the Liberal war room cruelly put out on their various websites hidden camera shots of Hudak delivering his stump speech to rooms more than half empty.

A more professional campaign by the Tories, focused on a positive and inclusive conservative vision of Ontario, would probably have come much closer to victory, especially in 905, where the same multicultural voters who had flocked to Harper deserted Hudak following the “foreign workers” foray.

The sense that his campaign had stumbled irretrievably came in the final days when the Tory campaign promoted a leaflet that was explicitly homophobic, slandered teachers as a profession and made bizarrely false claims about sex education in Ontario schools. It was as if some internal gremlin had set about sabotaging each potential growth area for the party, demographic by demographic. Having made any Ontario voter who had ever been humiliated by being singled out as a ‘foreigner’ feel insulted once more, the Tory campaign then attacked the tolerance of urban

Ontarians about sexual orientation. For a deadly icing on this political cake, they attacked the profession that had represented the key flash point of the Harris era: Ontario teachers.

On election night, the Hudak campaign failed to break through in Toronto or other parts of urban Ontario, where the gay community and those who see inclusive treatment of their friends in that community as something that makes them proud of their province. They lost the new Canadian communities in the arc of seats across northwest suburban Toronto that Harper had done so well in only a few months earlier, sweeping 21 of the 22 ridings in the suburban 905 belt around Toronto. They racked up wasted majorities in small town, rural and Eastern Ontario, dooming most of their star candidates to defeat.

The results were surprising in a number of tight races where strong incumbents, and several ministers, went down to defeat. But in the province overall the shift of 17 seats to the combined opposition parties for a government seeking a third term in a recession was hardly surprising. A more professional campaign by the Tories, focused on a positive and inclusive conservative vision of Ontario, would probably have come much closer to victory, especially in 905, where the same multicultural voters who had flocked to Harper deserted Hudak following the “foreign workers” foray. The NDP might have elected another half dozen seats with only a few more votes appropriately scattered. But given from how far behind they had come, given that very few voters had ever heard of their leader at the beginning of the campaign, they were pleased with their gains.

Since its glory days under David Peterson, the Ontario Liberal Party has been famous for a self-regard, a dismissive approach to those outside their political family. This arrogance, even more offensive to many voters after the Liberals’ eight years in power, was visible throughout the campaign. On election night the premier hailed his supporters and thanked his voters as if he had just won a massive new mandate. The messages from the Premier’s Office in the days following were not encouraging to those who thought a slice of contrition and humility were the appropriate response to leading a minority government. His team leaked to reporters the names of opposition MPPs they would seek to get to cross the floor. Some went so far as to spin that they expected to be in power for four more years and would govern as if they had a majority.

Horwath, in a gracious election night concession speech, called on her two opponents to govern in recognition of the voters’ nuanced message to all the parties, saying that she expected to meet with them soon to begin planning the new session. Hudak had done the same. In an elegant and emotional speech, Hudak made it clear that he is a far more interesting and nuanced politician than his campaign had permitted him to reveal. He avoided the kind of tub-thumping in which the Premier indulged. It was the sort of concession speech at the end of which professionals from every political tribe nod to each other and say, “He’ll grow. He’ll be back.”

Astonishingly, in response a week later, the Premier announced that he would not have any discussions with either of the two opposition leaders before the opening of the new Legislature. The government will want to listen to its worried friends and allies about the need to adopt a less provocative stance to governing, given that they will be selling a very bitter political message to Ontario voters in the weeks and months ahead.

The collapse in support for democracy that the electoral turnout reflects cannot yet be dissected for detailed analysis. It will be surprising, however, if the academic number crunchers, pollsters and psephologists do not point to a continuing decline in the participation of voters under 30 and to the hesitant participation of new Canadians. Even more sadly, such an analysis will probably reveal a widening class divide in the province between those with property and those without. It is the sort of voter disengagement for which Canadians have long sneered at the United States that we now appear to have allowed ourselves to develop.

It will not be easy to respond in policy or political terms to the delegitimization of the party elites implied by such a low voting rate. Efforts to reach out to new and young voters and discuss the reasons for their feeling of disempowerment will have to be an important step. Encouraging the parties to revive their local activist bases to include voters who are not merely aging white homeowners will also be key. No one in political life should dismiss the seriousness of a continued slide in participation.

It will be hard to win broad support for the tough measures any Ontario government will need to implement to regain fiscal credibility. It will be impossible if those who feel the most alienated from politics see governments’ decisions as deliberately favouring those who have and vote, over those who have not and don’t. The reasons for some of those voters’ disengagement can be seen from a car window in many parts of Ontario today.

The devastation and despair were visible to the leaders in this campaign, as never before. As the three leaders’ buses crisscrossed the province in a glorious late-summer September, they would have noticed how dramatically the province has changed. As recently as the last deep recession, the one that afflicted the Rae government in the early 1990s, Ontario was still mostly a prosperous province.

Today, a prosperity map of Ontario resembles a war zone after years of artillery pounding. Pockmarked by endless shuttered factories and dying shopping malls, many parts of Ontario now feature industrial bomb craters, as it were. Yet there are pockets of shining prosperity, often nearby. If you started your leader’s tour day in Waterloo and ended it in Welland, you would slide from glittering high tech prosperity to rust belt desolation.

The booming tech suburbs of Ottawa are only an hour away from the abandoned factories, motels and peeling main streets of a dozen nearby towns. The farther you travel from the 905 arc of prosperity that runs from Oakville to Oshawa, the more the failed motels, mills and abandoned farms make up the view from any highway.

The hollowing out of Canada’s richest province began long ago — along with the widening gap between the affluence of the skilled and the burgeoning army of the blue collar unemployed. But it is in this latest harsh recession that the holes have become visible in almost every region. Each leader faces challenges in addressing this new reality.

Premier McGuinty could not have failed to contemplate how much worse off some of these unhappy voters and communities will be when the cuts begin to bite. Hudak will no doubt have wondered about the wisdom of his claims of the hundreds of thousands of jobs his tax cuts were promised to deliver. Horwath, as a single mother, knows better than most the fear of a lost job or even the unbudgeted collapse of an old car and will have seen the fear in the eyes of Ontario voters as her bus rolled through yet another declining town.

As the Premier settles into his third term, his Finance officials will gingerly reveal how much worse the public fisc is than they had cheerfully informed him only three months earlier. The memories of warm latesummer campaign days will be replaced by the shock of the first early snow and chillier economic news by the week.

As they begin the inevitable slices into public expenditure in preparation for their first grim budget, one may hope that the Premier and his team recall those bereft faces and the sad, sagging cities and towns they roared through on their return to power. It is in the Wellands and Thunder Bays and Pembrokes that every cut in nurses and teachers and highway crews is felt first. And in the broken neighbourhoods of Ontario’s inner cities, every afterschool and child care cutback hits harder than in the wealthy condos nearby.

The Premier might even mutter a silent apology to Bob Rae for all the sport at his expense. Now it’s McGuinty’s turn to attempt the daunting task of balancing the demands of bond markets and child care, the demands of shrill economists and bankers versus angry laid-off breadwinners. Winter will come early for Ontario this year.

Photo: Shutterstock