Venezuela is in the midst of one of the worst economic crises it has ever experienced. People are starving, there is little to no access to basic necessities, electricity is being rationed, inflation will rise by 1,600 percent next year according to International Monetary Fund predictions, and the military has been sent into some cities to maintain order. In the last month alone, there have been more than 50 food riots, protests and mass lootings.

As reported by the New York Times, in a recent survey Simon Bolivar University found that 87 percent of people in Venezuela don’t have enough money to buy food, and according to the Center for Documentation and Social Analysis, 72 percent of monthly wages are being spent on food.

Decades of economic mismanagement, political corruption, and dependency on oil have made Venezuela particularly vulnerable to oil markets: as the price of oil fell, the Venezuelan economy collapsed. What is stark here is that only 10 years ago, Venezuela’s Caracas Stock Exchange was one of the best performing markets in the world, the country was the fastest growing in the Americas, the central government had a balanced budget, and the economy grew by 10.3 percent.

Venezuela’s recovery will depend on an oil price recovery, and also on the management of the country’s state-owned oil giant, Petróleos de Venezuela (PDVSA). However, the company is facing challenges: PDVSA’s oil production declined nearly 300,000 barrels per day (bpd) between May 2016 and June 2016, falling to 2.1 million bpd, a level not seen since 1990. Production is down in every region of the country for the first time since 2008. Barclay’s recently said that production could fall another 400,000 to 500,000 bpd by the year’s end. In addition, the company has billions of dollars in outstanding debt obligations that will come due by the end of the year.

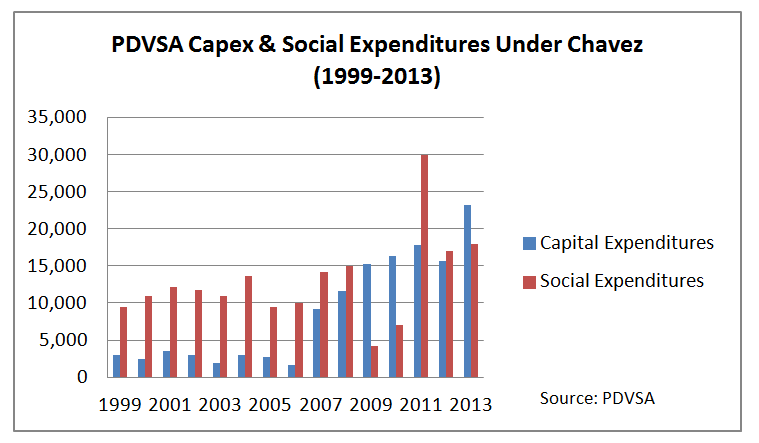

Overdependence on oil, the country’s socialist shift under former president Hugo Chavez, and the supernationalization of PDVSA have led to the current crisis. Now, with one of Chavez’s closest allies in his third year as president, little has changed, and the situation in Venezuela seems to worsen by the day.

But despite current challenges, long-term continual supply outages and political upheaval are not necessarily inevitable, as many analysts have suggested. Oil is killing Venezuela, quite literally, but as I explain below, it is also keeping it alive.

In recent months, oil companies such as Haliburton, Weatherford, and Schlumberger announced they were halting their operations in the country due to Venezuela’s inability to make payment on their services. On June 13, however, Schlumberger announced that it had entered into an agreement to increase its operations in the country. Schlumberger’s decision is not based only on recovering oil prices but also on multiple other factors that indicate Venezuela may be able to weather this storm, all thanks to oil. Here’s what’s keeping the country alive.

Commitment to bondholders: Venezuela is in a pay-the-debt-at-any-cost situation. According to analysts, including Francisco Monaldi of Rice University, Maduro is committed to paying bondholders, because if he does not they could seize state assets. Monaldi also suggests that the Venezuelan government is leveraging PDVSA assets for all that they’re worth, which is buying them time, but it also makes the assets far less valuable if they are eventually seized. The state has maintained its bond payments at the expense of being able to provide basic necessities for the citizens of Venezuela, making Venezuela’s bonds among the highest-paying investments in emerging markets (with an average yield of 26 percent). Since Chavez took power 17 years ago, Venezuela’s bonds have totalled a return of 517 percent for investors.

China: China is Venezuela’s largest creditor, having loaned the country US$65 billion since 2005. Because Venezuela does not have enough money to pay back its loans in cash, it sends China oil. In 2015, Venezuela sent China 600,000 bpd. Reports suggest that it is in talks with China for a one-year grace period on oil-for-loan deals, which could free up about US$3 billion in cash for Venezuela. Although it is unclear whether Venezuela will actually be able to meet its debt obligations to China, or even reach a beneficial agreement, some analysts think China could be the factor that decides Venezuela’s future.

Debt swaps: While PDVSA’s debt is not known, analysts put it anywhere from US$8 billion to US$12 billion. In an attempt to manage its debt, Venezuela is working on debt exchanges and bond offers with various oilfield service companies. Some deals may include a one-year grace period on interest payments. It has also been reported that PDVSA is offering certain oilfield service companies bonds in exchange for writing off amounts owing on contracts.

Exports: While Venezuela’s oil production declined to record low levels in May 2016, its exports sales to the US States rose nearly 4 percent in May to 762,000 bpd.

It appears as though President Maduro is set on staying in power by any means necessary, and the country’s ability to leverage its oil is certainly helping him do this. The country will continue to pay bondholders, while stalling for time on other debts. By milking its state-owned assets for all they’re worth, President Maduro will likely be able to hold on much longer than expected. China is playing an important role in keeping Venezuela afloat. Beijing has loaned Venezuela so much that Maduro may be in the driver’s seat of that relationship. All of these factors combined suggest that long-term power outages, decreases in exports or a markedly different administration taking office in the short-term are unlikely to occur. Venezuela’s complete dependency on oil has led it to this crisis, but it seems as though it may be the only thing to get it out of it.

Even if Venezuela’s oil production stopped (which is highly unlikely), or slowed further, there would be little opportunity for Canadian producers to capitalize on the situation. Canada is limited in its ability to increase market share in the US Gulf Coast (which is where most Venezuelan crude ends up) because of its lack of pipeline infrastructure. Shipping by rail is costly, and would not make sense given the current price of oil. As well, Canadian oil production consists primarily of mature oil-producing basins and capital-intensive oil sands extraction through mining and in-situ techniques. In other words, Canada would not be able to increase its production fast enough in response to a rapid decline in Venezuelan export.

Quite simply, if Canada wants to increase substantially its US Gulf Coast market share, it needs oil prices to increase and pipelines to be built.

Photo: Shutterstock.com

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.