(Version française disponible ici)

The public has the impression that the main taxes or contributions levied by Quebec’s public administrations – the Quebec government, municipalities or Retraite Québec – are constantly increasing.

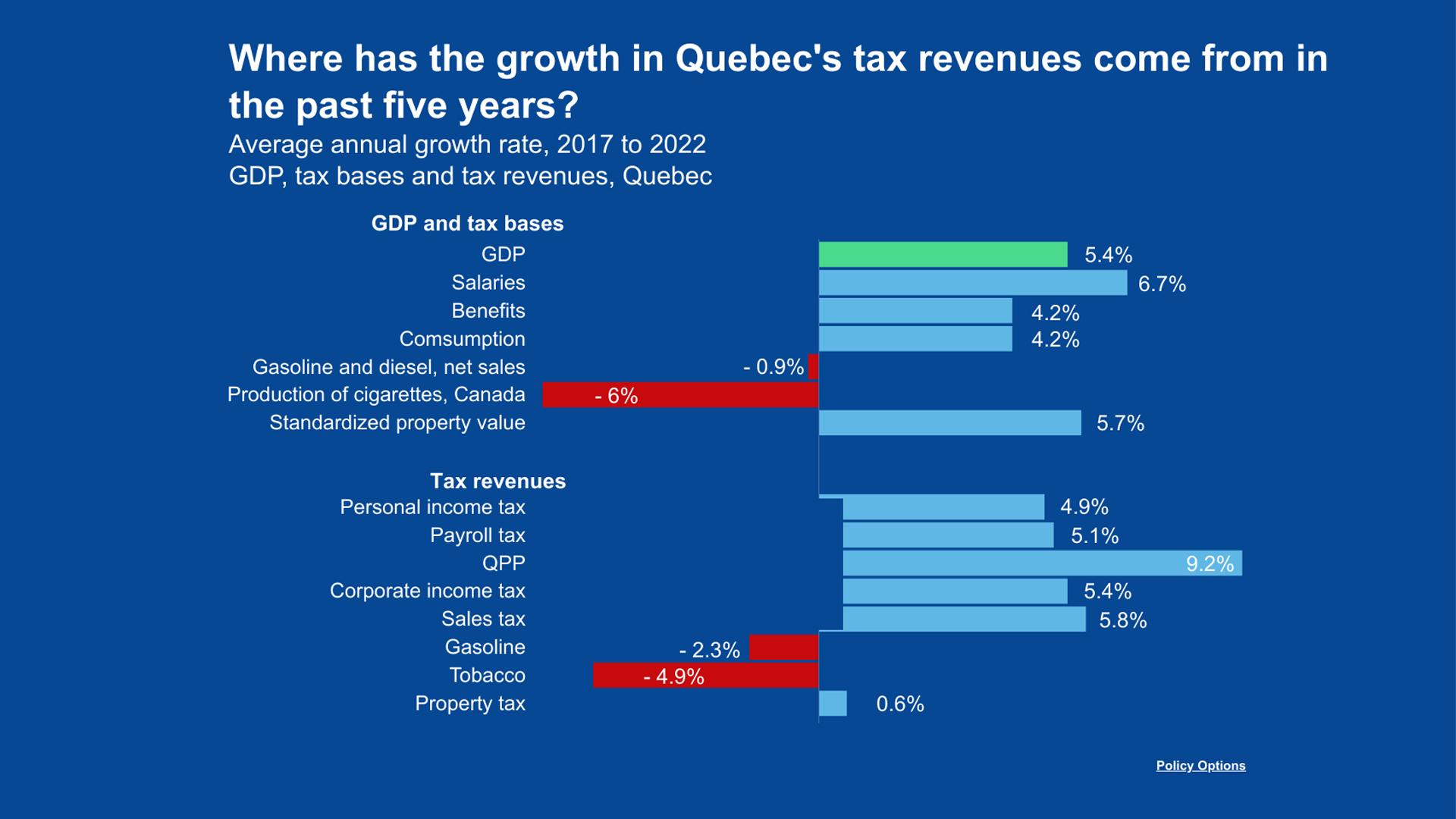

This can be seen more clearly by comparing the evolution of the average annual growth rate observed in Quebec between 2017 and 2022 for various components of GDP and revenues from various sources, as shown in figure 1.

Overall, while GDP – the size of our economy – grew at an average annual rate of 5.4 per cent, Quebec’s government revenues grew at an average annual rate of 5.1 per cent. On this basis, their weight in the economy has not increased.

Quebec income tax (+4.9 per cent) grew more slowly than GDP. The difference in growth can be explained by certain reductions in this tax and improvements in tax measures since 2017: reduction in the first rate of the tax scale, increases in the tax shield and the career extension tax credit, in particular.

The same is true of payroll taxes, primarily the Health Service Fund (HSF), whose average annual growth rate (5.1 per cent) has been lower than the rise in wages (6.7 per cent), which can be explained by the reduction in the rate at which small- and medium-sized enterprises contribute to the HSF.

Conversely, the 9.2-per-cent average annual growth in QPP contributions was well above wage growth. However, this is not due to a change in the contribution rate for the basic plan, but to the gradual addition, from 2019 onward, of a supplementary plan, which has the effect of enhancing future benefits paid to contributors to this supplementary plan.

As for Quebec’s corporate income tax, the observed growth of 5.4 per cent outstripped the growth in corporate profits over the same period (4.2 per cent) despite a tax rate that was reduced over the period for both SMEs and large corporations.

And while consumption grew at an annual rate of 4.2 per cent, sales tax growth reached 5.8 per cent. Although we don’t fully know why, it’s worth noting that QST collection has become compulsory for suppliers outside Quebec (for e-commerce, for example).

However, certain specific consumer goods have experienced negative average annual growth. This is particularly true of gasoline.

On the face of it, the drop in gasoline consumption is a welcome development, even if it has led to a 2.3-per-cent drop in revenues. But between the fact that revenues from the tax are used to finance transport infrastructure and the need to increase the use of environmental taxes, several factors militate in favour of increasing this tax, or at least indexing it.

Finally, it’s worth pointing out that one of the tax bases that has grown most strongly between 2017 and 2022 is property value, via average annual growth of 5.7 per cent. Yet it is also one of the tax bases with the lowest revenue growth (+0.6 per cent).

Make key Quebec public services universal for the cost of a Big Mac a week

How do taxes and public benefits evolve over the course of a taxpayer’s life?

This phenomenon can be partly explained by the reduction in school property tax. This began in 2018, first by standardizing the school tax rate by administrative region, based on the lowest rate in effect, and then by introducing a tax exemption on the first $25,000 of assessment. Starting in 2019, the government went further by applying a single rate for the whole of Quebec, standardized at 17.83 cents in 2019, then gradually reduced to 10.24 cents per $100 of assessment in 2022. Thus, if we focus on the school property tax collected by school service centres, we obtain an average annual decrease of around 13 per cent between 2017 and 2022.

Looking exclusively at property taxes collected by municipalities, the annual growth rate can be estimated at 2.4 per cent. This rate remains well below the growth in standardized property value or GDP. On this basis, lower property tax rates and the decision by cities not to recover the tax room freed up by the reduction in the school tax have had the effect of reducing the relative importance of property taxes, both in terms of the Quebec tax structure (from 9.4 per cent in 2017 to 7.3 per cent in 2022) and in relation to GDP (from 3.6 per cent to 2.8 per cent). From this perspective, the property tax increases announced by municipalities in autumn 2023 take on a different meaning.

Further findings on Quebec’s public finances and spending can be found in Bilan de la fiscalité au Québec – Édition 2024.

This is the second of two articles analyzing Quebec and Canada’s taxation. The first is here.