Global concerns regarding preventable maternal and childhood mortality prompted the Canadian-led Muskoka Initiative on Maternal Newborn and Child Health (MNCH). Through this initiative Canada, partner nations and private foundations have committed US$7.3 billion to address the global health crisis of preventable maternal and childhood deaths. In September, Prime Minister Stephen Harper addressed the United Nations Summit on Millennium Development Goals, urging countries to pay direct attention to goals 4, 5 and 6, which are aimed at reducing maternal and childhood mortality. Over half a million women die during childbirth and 9 million children die before the age of five because of lack of access to factors such as clean water and immunizations.

The investment of $7.3 billion is focused on advancing the quality and dissemination of health care in developing nations. Parallel strategies incorporating healthy brain development, based on leading Canadian research and policy, would vastly increase the rate of return from this significant investment. This article will review the importance of early brain development and early human development in promoting a healthy future for society.

Early brain development in the prenatal period and early years of life impacts health, learning and behaviour throughout the lifespan. The brain develops rapidly in the early years, a time at which one’s experiences interact with genetics to shape the developing brain. Epigenetics describes how experiences affect gene expression, by enhancing or depressing the translation of genes into proteins. Epigenetic modifications affect everything from how we respond to stressful events to our risk for disease and our ability to learn. Positive early conditions such as a stable and nurturing caregiver, a language-rich environment and access to good quality nutrition, medical care and community supports provide the necessary foundation for lifelong health and well-being. Negative early experiences including maltreatment, poverty and poor health result in an increased risk for poor outcomes including chronic diseases, poor mental health and low educational achievement.

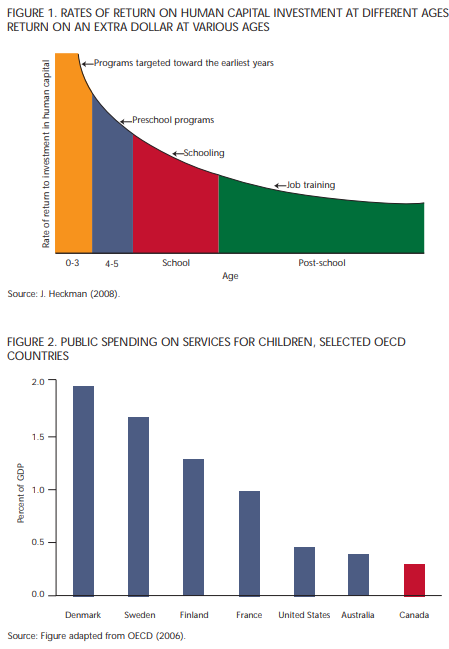

James Heckman, an American economist and Nobel laureate, has highlighted the economic implications of investing in early brain development through research on the impact of preschool programs. Heckman argues that investing in early childhood development programming results in greater returns than investments made in the later years of life such as post-secondary education and job training (figure 1).

A 2006 study conducted by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) compared the investments made in early years programming in 20 developed countries as a percentage of each nation’s GDP. While average investment across the countries was 0.7 percent, Canada invests only 0.3 percent of its GDP toward early years programming. Nations such as Denmark, Sweden, Finland and France spend 1-2 percent of their GDP on supporting early child development (figure 2).

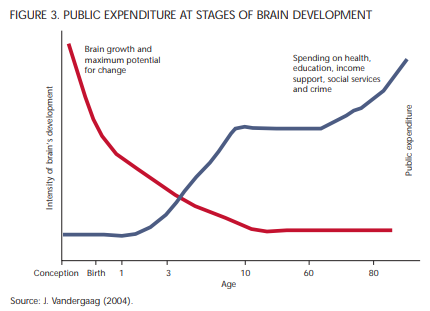

Taking into account current research on the sensitive periods for early brain development, it makes sense that substantial public expenditure should be focused on the first three years of life. As demonstrated in the OECD report, Canada is failing to make investments where they stand to achieve the greatest return. The sensitive period for investing in Canadian children is being neglected and majority of investments are being made after developmental trajectories have been set and potential for change in terms of brain growth is significantly reduced (figure 3).

Inadequate investment in early child development has caused Canada to fall behind other industrialized nations with respect to supporting the development of young children. In 2008, the UNICEF Innocenti Report Card revealed that Canada met only 1 out of 10 benchmarks for transition to early childhood education and care. Of the 25 OECD countries included in the report card, Canada and Ireland tied for last place, meeting the fewest benchmarks.

Canada also fails to meet the standards of its industrialized counterparts in two other important areas, infant mortality rate and low birth weight. Infant mortality rate (IMR) is defined as the number of newborns who die during their first year of life, and has generally been identified as the single best indicator of population health. Dennis Raphael’s 2010 article “The Health of Canada’s Children” reveals an upward trend from 5.2 infant deaths per 1,000 live births in 2001, to 5.4 in 2005, placing Canada 24th among 30 OECD countries.

Also considered to be an important indicator of population health is the incidence of low birth weight, as it is associated with numerous health problems occurring across the lifespan such as a weak immune system and neurological issues. Although Canada ranks 9th out of the 30 OECD countries, the disparity across Canada is discouraging, with 43 percent more low birth-weight babies found in the poorest income quintile than in the richest quintile.

In general, the OECD countries with lower IMRs and lower low-birthweight rates than Canada are, with respect to GDP, less wealthy. This indicates that the wealth of a nation cannot be used as the sole predictor of maternal and child health. Although Canada is a wealthy nation, the 2009 Innocenti Report Card indicated that the child poverty rate in Canada was an alarming 11.3 percent. Recently, researchers have begun to examine environmental and social factors to explain Canada’s deficits in child development. The social determinants of health are nonmedical factors influencing health, including early child development, income, education, employment, housing, food security, working conditions and the quality of health and social services that are available. “The Health of Canada’s Children” has suggested that these social determinants have more influence on development than one’s genetic makeup. This aligns with research on epigenetics, which shows that developmental trajectories are determined largely by one’s early environmental experiences.

Monitoring early child development is critical to understanding how policy impacts the health and well-being of children. The Early Development Instrument (EDI), developed at McMaster University, measures the developmental status of kindergarten children across five domains. The EDI has been implemented across Canada and internationally. Community maps of EDI results indicate the proportion of children vulnerable on one or more domains of the EDI. Vulnerability rates across communities in Canada vary greatly, from lower than 10 percent to higher than 70 percent. Children who are vulnerable in kindergarten often don’t catch up, resulting in poor academic achievement and lower employability. It is important to note that the majority of vulnerable children do not come from poor families; they are in the more populous middle class. The proportion of child vulnerability in Canada threatens to severely compromise the nation’s future economic growth.

Failure to invest substantially in early human development results in high costs to society in many areas. Lifelong issues related to early development include health issues such as obesity, diabetes, heart disease and poor mental health; education issues such as lower graduation rates and higher unemployment; and behaviour issues including higher rates of crime and substance abuse. It is estimated that the cost of mental health and addictions to Canadians is $100 billion annually. Heckman’s analysis of the cost of crime to

Inadequate investment in early child development has caused Canada to fall behind other industrialized nations with respect to supporting the development of young children. In 2008, the UNICEF Innocenti Report Card revealed that Canada met only 1 out of 10 benchmarks for transition to early childhood education and care.

Canadian society is over $100 a year. Economic analysis by the Human Early Learning Partnership has concluded that at current vulnerability rates measured by the EDI, British Columbia is forgoing 20 percent GDP growth over the next 60 years, equivalent to investing $401.5 billion at 3.5 percent — a figure that is 10 times the province’s current debt load. This analysis can be applied across Canada, with similar rates for each province based on population.

Where does Canada go from here? There are two critical issues that urgently require remediation by the federal government. First, the proposal to improve child and maternal health in developing countries needs to incorporate strategies that promote healthy early brain development. Based on the societal and economic impacts seen in Canada, it is clear that failing to dedicate resources to ensure positive developmental trajectories produces expensive repercussions that far exceed the initial investment required. Initiatives focused on improving child and maternal health in developing nations need to include services that support healthy brain development to ensure sustainable human development.

Second, maternal and child health is not an issue solely affecting developing countries; it is also threatening the well-being and sustainability of Canadian society. Promoting healthy early brain development in Canada requires policy, level change that directly influences environmental experiences on development. Providing supports and resources that foster positive environments for new families and young children needs to be prioritized to achieve the best developmental outcomes.

At present, an annual investment of approximately $22 billion toward social infrastructure is necessary to reduce Canada’s child vulnerability rates. At a provincial level it is estimated that Ontario would need to increase its investment by $8.28 billion per year, with almost half of this being put toward early childhood education and care. Alberta and Saskatchewan would require increases of $2.96 billion and $883 million per year respectively. The investments would go toward spending in the areas of time (increased parental leave), resources (income and employment supports) and services (childhood education and care).

While on the surface this may seem a costly investment to make, the cost to society of the status quo far outweighs the investment. Failure to invest in children and their families in the critical early years period will result in a cohort of developmentally vulnerable individuals who will be unable to reach their full potential and compete in an increasingly competitive global market.

Investing in early childhood experiences has the potential to deliver economic and social returns in a very short period of time. These “returns” can be demonstrated in as little as five years as the first cohort of children reaches kindergarten “ready to learn” with the potential to develop the skills they will require in the later stages of life and ultimately in the labour market. Policies that support young children and families would also have immediate returns to society. The Human Early Learning Partnership has identified a number of potential gains including attainment of work/life balance for parents, reductions in poverty and vulnerability rates producing savings in health costs, decreased expenditures on child welfare from fewer children entering the system and fewer costs associated with the family and youth justice system.

Decisions regarding maternal and child health need to be made from an informed position on what is necessary for healthy brain development to occur. This requires a commitment to providing current and accurate information to those individuals charged with making decisions that affect outcomes for both young children and their families. Such individuals include but are certainly not limited to health care professionals, child welfare workers, and family and provincial court judges and lawyers, as well as new and expecting parents.

It is clear that attempts to support child and maternal health are not adequate without the promotion of positive early childhood environments and experiences. Furthermore, the science of early brain development is a matter requiring the attention of the international community. Healthy human development is an issue affecting both developing and industrialized nations, and its achievement has the potential to create future generations with increased health, better quality of life, more productive labour forces and ultimately successful and sustainable communities on a global scale.

Photo: Shutterstock