Local election campaigns can have a small but decisive impact ─ anywhere from 4 to 10 per cent ─ on some riding vote results. This is significant and can make the difference between winning and losing, not only at the constituency level but also nationally. In the 2021 election, for example, preliminary results show that more than 30 ridings had a gap of less than four percentage points between the first- and second-place candidates – a crucial factor in a minority parliament. Despite this, the day-to-day work of individuals on local campaign teams is not well-understood outside the relatively small circle of party activists serving in the electoral trenches.

Volunteers are the lifeblood of local campaigns. Sometimes they are long-time party activists who sit on the riding association board and work in every election. Sometimes they are associated with the candidate personally or want to advance particular policy issues. In 2021, however, many campaigns reported that they had trouble recruiting volunteers because even dedicated partisan workers were burned out from a year and a half of pandemic turmoil.

Some campaigns are moving toward not only paying campaign managers ─ a trend that started several decades ago ─ but also paying workers in other positions. Some campaign managers have reported paying crew members for delivering signs and cleaning them up after the election. Several Ontario Conservatives have confirmed that some ridings were paying canvassers.

Full-time political staff, who are normally employed by ministers or members of Parliament, also support local campaigns. Because their jobs depend on their MP or party getting re-elected, they are usually highly motivated to work on the campaign, but may not do so while on the public payroll according to the House of Commons guide to members’ allowances and services (chapter 11, page 29). Many take unpaid leave to campaign, often volunteering in their boss’s riding. Those who don’t take unpaid leave may campaign only outside normal office hours. Staffers generally recognize that supporting the party’s campaign effort demonstrates commitment to the team and is unspoken recompense for the privilege of keeping their jobs after the election.

Despite the significant different organizational structures of local campaign teams as a result of party tradition, region, nomination type, relationship to the national party and/or competitiveness, their key activities are remarkably similar: communicating with voters to boost the candidate’s profile, identifying supporters, and getting out the vote on election day (commonly known as GOTV).

The campaign manager assumes overall responsibility for the campaign. This means advising on communications strategies and messaging, setting and managing the budget, signing off on all expenses including those for printing, website development and advertising, and establishing priorities for canvassing and GOTV efforts.

The director of communications typically determines the approach to advertising and publicity, including how to allocate resources across various communications options, and must use judgment in applying national party messaging and templates to the specific situation. Although printed literature that is left at doorsteps or sent by mail is important, digital content is becoming the preferred method for campaign communication. Facebook advertisements, for example, allow campaigns to deliver messages to voters, track voter engagement in response, and even harvest personal information (when voters can be induced to provide it).

The “sign war” on arterial roads and in residential neighbourhoods is perhaps the most public manifestation of an election campaign. Signs are often seen as an indication of the campaign team’s operational strength and momentum, and its ability to increase name recognition for the candidate and buoy supporters’ enthusiasm. However, some campaign activists believe signs cause more trouble than they are worth. “I hate them a lot,” said one Atlantic Liberal campaign manager. “Signs don’t vote.” Ideally, he said, volunteers should prioritize identifying voters instead. However, campaigns must demonstrate a presence, so signs are deployed to create the impression of momentum early in the campaign and toward election day, regardless of whether it exists.

Just as posting signs is designed to boost the party and the candidate’s name recognition in the riding, so are other campaign activities.

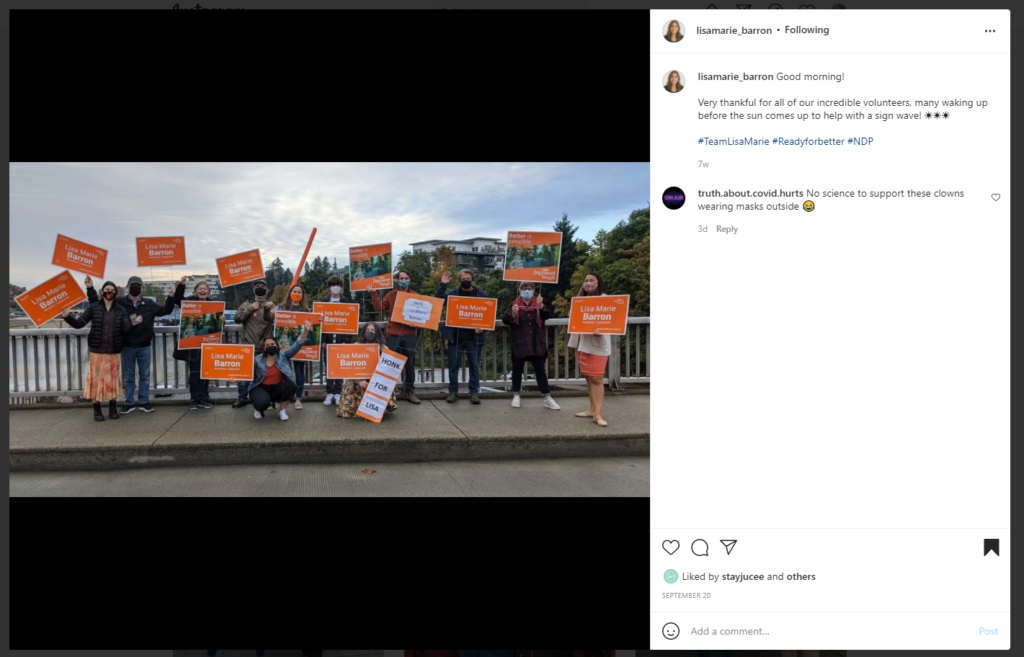

Volunteers are often marshalled for “burma-shaves,” where volunteers gather with the candidate along an arterial road to wave signs and cheer to attract attention from passing motorists. (The term is a nod to an American shaving-cream company known for its rhyming road signs between the 1920s and the 1960s.)

“Mainstreeting” also increases attention for the candidate. A contingent of volunteers gathers in an area where there is concentrated pedestrian traffic to wave signs and button-hole passersby. “You wave your signs until somebody kicks you out or says that you’re not allowed to be there, and then you move on to the next one,” said an NDP campaigner. Unlike demonstrations along a highway, mainstreeting allows volunteers to ask voters for support, and the responses can be collected and entered into the campaign database. This is useful but does not lead to systematic voter identification.

Candidates also canvass voters to identify party supporters and ensure they vote on election day. This is about harvesting data efficiently, not about public engagement and persuasion.

As one Ontario Liberal said, “probably 95 per cent of what you’re doing is just identifying your vote. Your goal is not to change minds. It’s just to find out where people are and move on.”

Typically, volunteers are dispatched throughout the riding to knock on doors and ask residents about their voting intentions. If they are supporters they might be asked if they will also take a lawn sign, volunteer or donate. Canvassers must judge at the doorstep how to code each voter: are they party supporters, leaning toward the party, undecided or hostile? These judgments determine the soundness of the data. Recording voters incorrectly may mean that the campaign targets the wrong people when trying to get out the vote on election day.

Campaigns do not try to knock on every door. Rather, parties canvass where they can quickly identify the most supporters. Teams are assigned to canvass designated areas of the riding, and volunteers sometimes stop at some houses and skip others. Apps help with this task. The Liberal smart phone app, for instance, has more capabilities than those used by other parties. It is predictive of individuals and can give house-by-house instructions to canvassers to maximize contact with likely supporters.

Campaigns identify voters so that they can encourage their supporters to vote. Early on election day volunteers will start delivering “don’t forget to vote” door hangers affixed with information about the correct polling locations to identified supporters. Later in the day they will return to drop off reminder cards or follow up with phone calls to ensure their supporters get to the polling stations. Central party campaigns may also pay phone banks to make additional calls to identified supporters in ridings they consider especially winnable.

Having up-to-date data is vital. Neighbourhood captains keep the GOTV manager informed of where volunteers are going, so the campaign can efficiently route resources as needed to areas not yet canvassed. A representative for each candidate is also entitled to collect “bingo sheets” at polling stations under Elections Canada’s guidelines for candidates’ representatives. These are lists Elections Canada officials will provide to candidates regularly throughout the day showing who has already voted. This information helps campaigns to focus on supporters who have not yet voted, so they can be reminded again and perhaps offered a ride to the polling station.

Authorized representatives of the candidate can receive Elections Canada credentials as scrutineers to observe the voting on election day, and after polls close during the counting of ballots. Scrutineering is unlikely to make much difference in the final count, but having a presence provides assurance that the rules are properly enforced. Allegations of vote fraud and disputes over access for partisan poll watchers in the 2020 United States federal election underscore how important transparent voting procedures and routine access for partisan scrutineers are to the integrity of Canada’s electoral system.

The 2021 election raised questions about local campaign workers. Was volunteer burnout a unique event due to the pandemic? Or is partisan engagement in general waning, as some senior activists have suggested? If so, is this accelerating the trend toward paying more campaign staff? Will the increasingly robust capacity of national party headquarters to gather and analyze data reduce the importance of local canvassing? What implication would this have for how parties engage voters?

It has been 30 years since the Royal Commission on Electoral Reform and Party Financing (the Lortie Commission) inspired detailed research on local campaigns. Now renewed effort to investigate these questions is warranted.

Cet article présente une version abrégée d’un chapitre tiré d’un ouvrage qui sera publié en 2022 chez UBC Press. Il fait partie du dossier spécial Au cœur d’une campagne de terrain.