OTTAWA – Fewer federal public servants went on long-term disability during the pandemic compared to previous years, but of those who did, more than half of them suffered depression and other mental health issues, which are expected to worsen with the isolation of working remotely.

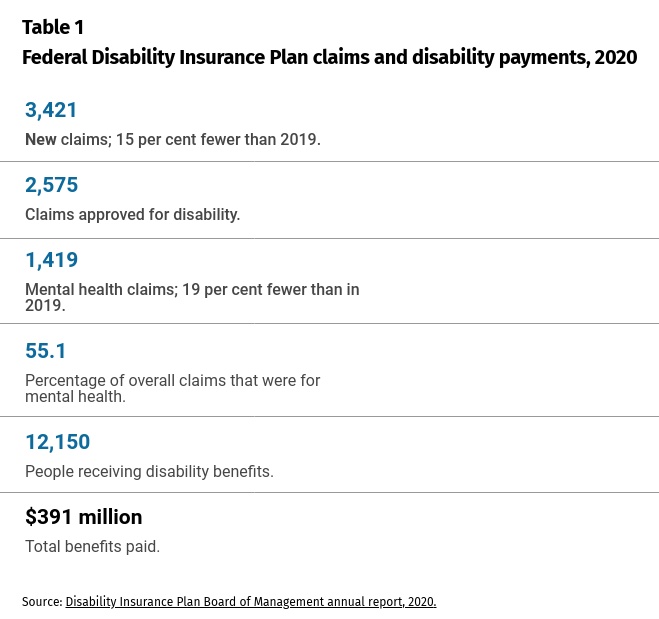

Public servants, like all Canadians, filed fewer long-term disability (LTD) claims during the first year of the pandemic. Both physical and mental health claims declined about 15 per cent from the previous year, but the proportion of approved claims related to mental health spiked to a historic high of 55.1 per cent (Table 1, below). They previously peaked at 54.4 per cent of claims in 2019.

The private sector also saw overall claims decline, but the share of mental health claims hovered around 30 per cent.

The public service has conspicuously stood apart for years for having a higher proportion of mental health claims than other employers. Mental health, led by depression and anxiety, is by far the biggest driver of claims, followed by cancer as a distant second at 11.5 per cent of claims.

All employers, however, are bracing for an increase in mental health issues as the pandemic eases and they shift to a hybrid workforce. Most public servants have worked at home for nearly two years and are expected to return as hybrid workers, a mix of working in the office and at home.

Mental health is the top concern for a post-pandemic workforce, according to a 2021 health-care survey by Benefits Canada, a pension and benefits publication. Employers expect mental health challenges related to anxiety arising from the isolation and loneliness of working at home (page 38 of the survey). They also predict anxiety among workers in the office who are unsure if co-workers are vaccinated.

Will nooks and lounges replace the office in the public service?

The pandemic upended the federal workplace. What comes next?

This week’s throne speech flagged the importance of mental health services in the aftermath of the pandemic, while the Mental Health Commission of Canada warned the mental health impacts are “delayed, complex and long-lasting” and could take time to emerge.

That’s why some argue it’s time the government get a handle on why its mental health claims are persistently high, particularly as it shifts to a hybrid workforce and the nature of work and the office changes.

“Why? It’s the million-dollar question,” said mental health and benefits expert Joseph Ricciuti, principal at Eliza Consulting Group.

“Things seem to have got even worse over the years. The government has to figure out how to deal with this issue. The perplexing question is what’s causing this? Why do federal government employees still have a level of mental health issues that results in claims so much higher than the rest of the industry?

Mental health claims have more than doubled since the 1990s, when they made up 24 per cent of all claims. They hovered on either side of 45 per cent of all claims from 2008 to 2018, when they jumped to half of all claims.

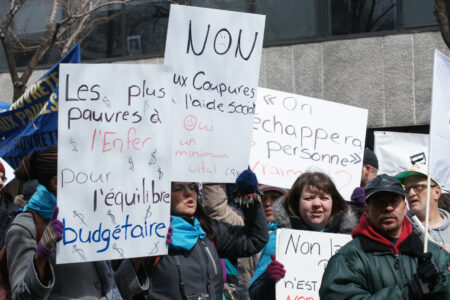

Chris Aylward, president of the giant Public Service Alliance of Canada, argued when one out of two approved disability claims is for mental health, more must be done to manage workplace and social stresses as the workforce transitions to hybrid work.

The federal government has taken many steps over the past decade to make mental health and workplace wellness a priority. Former privy council clerk Michael Wernick tied a portion of deputy minister performance pay to building a respectful workplace.

It has a mental health strategy, created the Centre of Expertise for Mental Health in the Workplace, appointed disability management officers in departments and mental health ombudsmen and created programs to help employees cope and build resilience during COVID-19.

The financial strain of rising mental health came home to roost in 2019, when the government decided to pump $313 million into the disability plan to put it on “sounder financial footing.” The 50-year-old Federal Disability Insurance Plan, managed by Sun Life Financial, is the biggest in Canada and provides coverage for 255,000 public servants.

The plan’s latest report shows the plan ran yearly deficits in 2018 and 2019 and all signs suggested another deficit in 2020. Wages had also increased with new contracts in 2014 and 2018, which meant higher income replacement payments, and the plan’s returns declined with low interest rates.

Treasury Board said the plan had to be refinanced to meet the 40 per cent of premiums threshold required for the reserve, which sets aside funds to cover future benefit payments.

But then the pandemic hit, which ended up saving money for the plan. Claims decreased rather than increased and all the money from the government and premium increases from employees generated a $485 million surplus by the end of 2020. That surplus hit $651 million by October 2021, said one official, who is not authorized to speak publicly about the plan.

It’s unclear whether this cash injection will be enough if claims climb back to pre-pandemic levels or are higher, as some fear.

But Ricciuti said “throwing more money at reserves” is a “rear-view mirror” solution for a problem that needs money invested at the front-end when workers first get sick and take time off work. “If you don’t take action on the front end, you could be exploding with claims on the back end.”

Officials familiar with the plan said it was expected that mental health claims could fall because people have been working at home. It’s also suspected people who delayed seeing doctors or being treated for conditions during the pandemic could show up later in a surge of LDT claims.

Some argue the long-term trend of higher claims is also a result of the government’s drive to remove the stigma around mental illness. Attitudes have changed, especially among younger workers, who are more willing to tell bosses they are stressed or depressed, take time off and use services.

The pandemic’s stresses affected the health and mental wellbeing of all Canadians. Lives have been upended as people lost jobs or were sent home to work. Some were initially scared about getting sick and dying, and then loneliness and isolation set in.

Also, public servants delivering the government’s COVID response worked flat-out and are exhausted and burned out, with some facing post traumatic stress disorder.

But Ricciuti argues the government needs to examine its sick leave and disability regime to figure what’s going wrong. Is the plan design outdated, does it have the proper tools to prevent, identify and treat mental health?

How COVID-19 could reshape the federal public service

Without good data we can’t improve mental health care

Fix the mental health system as part of an inclusive recovery

A longstanding complaint is that public servants languish on sick leave and don’t get the up-front case management and rehabilitation services they need when initially booking off work. The longer they spend on short-term disability, the more likely they will end up on long-term disability.

Ricciuti said studies have shown that employees on disability for more than 12 weeks have a 50-per-cent chance of never returning to work. That slips to 32 per cent after a year and less than five per cent after two years.

“By the time they get to LTD … it’s often too late,” said Ricciuti.

Public servants, however, don’t have a short-term-disability plan. Instead, they get 15 days of fully paid sick leave per year, which can be banked and carried over year after year. They can’t even apply for disability until after a 13-week waiting period or until they exhaust their sick leave credits, whichever is later.

The government has tried for the past decade to overhaul its sick leave and disability plan to help sick workers get better and back to work faster.

The most controversial move was a proposal initiated by the Harper government to get rid of sick leave and replace it with a short-term disability plan. The proposal sparked a massive outcry and galvanized federal unions into a solidarity pact against it.

Many of the unions eventually accepted a modified proposal that the Liberals introduced, but attempts to negotiate the details fell apart in the last round of collective bargaining. That plan proposed getting rid of the existing 13-week waiting period. The proposal may be revived as the government moves to a hybrid workforce.

This article was produced with support from the Accenture Fellowship on the Future of the Public Service.