In the fall of 2016, the Ontario Liberals signalled they were gearing up for the 2018 provincial election. Pat Sorbara, a key strategist in Premier Kathleen Wynne’s office, was moved into party headquarters as CEO and director of the Liberal campaign. This was 20 months before the actual election date, set for June 7, 2018. During Stephen Harper’s second term in power, the government announced infrastructure funding for small towns and cities using large novelty cheques that prominently displayed the Conservative party logo. The current Liberal government purchased cardboard cutouts of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau to use at Canadian missions and government events in the US when the real-life Trudeau was unavailable. What is going on?

Canadian party politics has become deeply entangled with the phenomenon of “permanent campaigning,” as explored in a new volume I co-edited with Alex Marland and Thierry Giasson. A permanent campaign means electioneering between elections, when no official campaign is underway. The concept neatly captures the essence of employing ─ while in the process of governing ─ strategies and tactics that are usually used in the campaign setting. Political parties practice permanent campaigning for two reasons: to advance their current agenda, and to position themselves well for the next electoral battle.

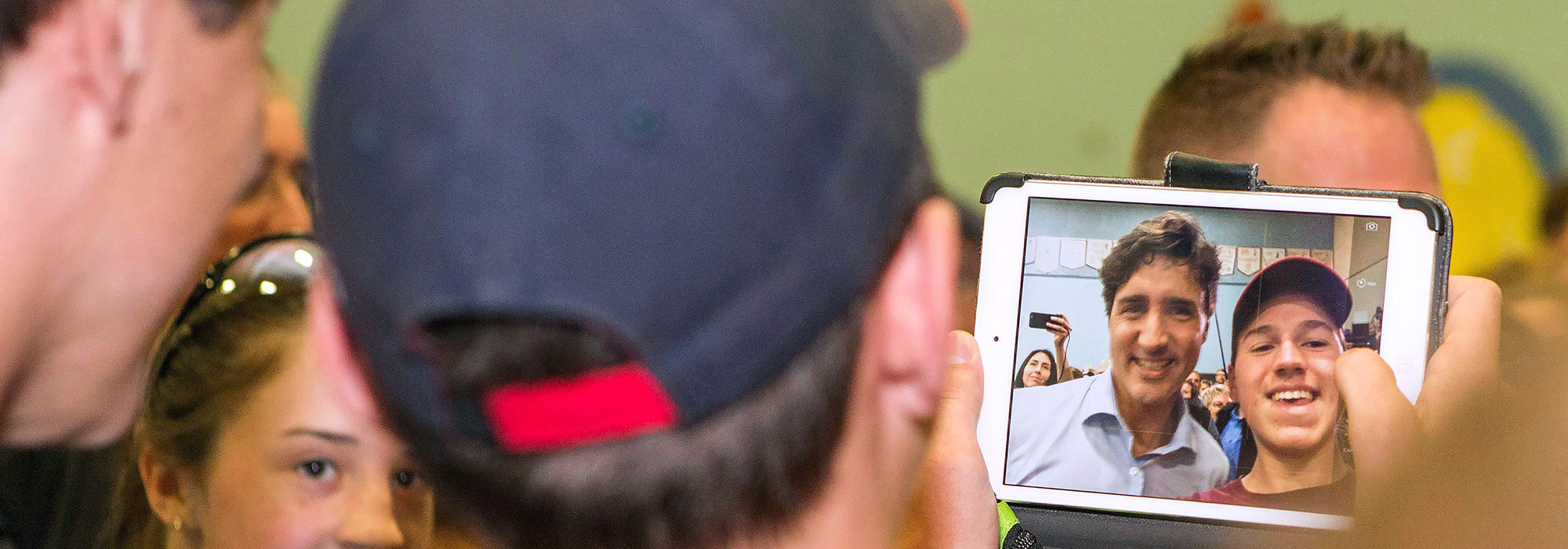

The governing party has a particular advantage, since it can use the levers of power to assist its cause, either through the dispensing of public goods and the procurement of market intelligence using government public opinion surveys, or through the use of taxpayer dollars to trumpet government policies by means of television and radio advertising. Permanent campaigning also means that party leaders are carefully managed in order to project and protect a preferred image. The skilled staffers operating within the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO) decide to either limit the prime minister’s interaction with the media and the public or encourage it with photos or scripted comments to the press that reinforce the “message” it wants to deliver to Canadians.

Every decision, every communication, every event is managed in order to win specific pockets of public approval. There’s a reason Justin Trudeau was photographed jogging near a group of prom goers in Vancouver last spring; the 18-24 age group is a key target market for votes in 2019. The photo was quickly uploaded to Twitter, and within hours it had thousands of “likes” and retweets. Trudeau also stayed long enough to pose for pictures with the students, reinforcing his image as youthful and approachable. Governing and campaigning have become one and the same.

Several factors are contributing to the permanent campaign. I’ll mention just two here. The first is the decline in partisanship among voters. Election studies show that political parties have fewer loyal supporters who they can rely on from one election to the next. Because of shrinking pools of supporters, parties must put together new coalitions of voters every four years to win, or retain, power. Identifying and reaching out to these floating segments of voters takes time, money, and reliable information about citizens.

The second factor involves the rules regulating party financing. Changes were made under Jean Chrétien and Stephen Harper’s administrations to limit and then stem the tide of donations flowing from corporations, unions and wealthy individuals. Public subsidies that were introduced to partially fill the financial gap were phased out under Harper. As a result, the need to fundraise directly from individual Canadians became a driving force in party operations. Knowing who might donate, how much and when is now crucial.

The permanent campaign has also created an insatiable appetite for data; parties have a strong incentive to gather as much information about us as they can, and the pace data collection is intensifying. Bits of data points when put together can paint a picture about any person’s propensity to support a party, take a lawn sign, and/or donate money. In other words, information is used to develop and refine analytical models that can help predict voter behaviour. How these details are gathered varies: it might be a call to a constituency office or a knock on the door during an official campaign. The parties input every piece of information they can gather into specially designed databases, and the information they collect is then used to analyze, target and court blocs of voters.

The challenge here is that there are few ─ if any ─ rules governing how parties collect, store, or use the data they gather about voters.

A new, vital piece of information will be added for the 2019 contest: Elections Canada is now mandated to provide political parties with information about who actually cast a ballot. The “Statement of the Electors Who Voted on Polling Day,” is not publicly available, but it is a generous gift to permanent campaigns. The parties can focus their limited resources on those voters who are most likely to turn out.

The challenge is that there are few ─ if any ─ rules governing how parties collect, store, or use the data they gather about voters. Privacy issues are paramount, but legislation that applies to public institutions does not extend to private organizations, and political parties fall into this category.

There are certainly arguments in favour of permanent campaigning. Parties are now paying closer attention to the wants and needs of voters. They are encouraged to deliver on the election promises they make. A celebrity prime minister who is more outgoing and available is putting Canada on the map again. But, in large part, the advent of permanent campaigning is troubling for scholars of Canadian politics. While it’s been a feature of the American political landscape for decades, it has now taken hold here with a vengeance, especially with the introduction of fixed election dates, which encourage parties to “ramp up” for a campaign battle long before Parliament has officially been dissolved.

The drive to compete and win, in this instantaneous and interactive digital era, means the permanent campaign has extended into our democratic institutions. This means the traditional processes of Parliament are readily exploited if they provide a party with partisan advantage. The permanent campaign encourages more omnibus legislation so that election promises can be delivered in bulk. Time allocation measures mean that Bills favoured by the governing party are passed more quickly, thus limiting parliamentary debate. It encourages requests for prorogation when the preferred government narrative is threatened and, as a consequence, it restricts the ability of opposition parties to carry out their key scrutiny and accountability functions. The partisan exploitation of government resources and procedural processes in Parliament poses a threat to how Canadians are governed. In other words, to varying degrees the proper role of Parliament is sacrificed in the battle to win the hearts and minds of select groups of voters.

The proper role of Parliament is sacrificed in the battle to win the hearts and minds of select groups of voters.

Is there a way out? Perhaps. One possibility is to regulate political party financing outside of the writ period and impose annual spending limits. This could limit a party’s ability to launch attack ads against their opponents between elections. Banning partisan government advertising is another idea that the Liberals are pursuing. Reintroducing public subsidies for political parties might also reduce their ferocious appetite for information about Canadians, a key part of fundraising efforts. But once the norms attached to the functioning of parliament are modified, future governments may find the convenience they offer difficult to relinquish. The Trudeau Liberals loudly bemoaned Harper’s penchant for omnibus legislation, but since forming government they have introduced at least one mega-Bill of their own.

There is little doubt that political parties in Canada have embraced permanent campaigning. They are under pressure to grow their databases, fundraise, reach out to new and diverse voter groups, and undermine their opponents at any opportunity. Every political activity is viewed through the lens of winners and losers, and tools that can provide electoral leverage are put to use. It could be said that it has always been so, but in the past there was not the sense of calculated purpose as there is today. Political scientists have been trained to study election campaigns as they unfold during the official writ period, but we need to recalibrate and pay considerably more attention to what happens between elections. We’ll find there is much to study.

Photo: Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau takes a selfie with guests at Centre communautaire Sainte-Anne, where he stopped to talk with athletes of the 38th Finale des Jeux de l’Acadie, in Fredericton, New Brunswick, Thursday June 29, 2017. THE CANADIAN PRESS/James West

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.