The divide between science and the humanities was famously laid out by English chemist and novelist C.P. Snow in his “two cultures” lecture more than 50 years ago, but science and the humanities have been at each other’s throats for centuries. That antagonism is only sharpened by the new questions science throws at us all the time: The human genome. Big data. Drone warfare. Scientific advance carries consequences for how we live and how we see ourselves, often leaving us polarized and unsettled.

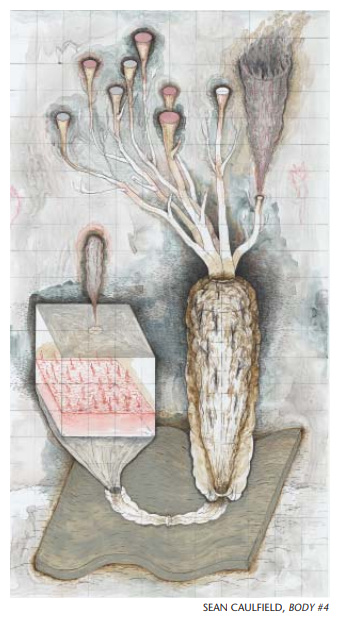

The mood is reflected in the art that appears in this month’s magazine alongside a collection of articles about the role of science in the public realm. Most of the artwork is from the exhibition ”Perceptions of Promise: Biotechnology, Society and Art,” a collaborative project that assembled an international group of artists, philosophers, legal scholars and scientists in Calgary’s Glenbow Museum to reflect on emerging biotechnologies, with a focus on stem cell research. The art is strikingly original, from sculptural forms created from drawings that sample from scientific script.

The result, says Sean Caulfield, a Centennial Professor in the Department of Art and Design at the University of Alberta whose ink and acrylic Body #4 graces the cover, “is intended to point viewers toward a contemporary context in which advances in technology are rapidly changing our relationship to the natural world, biology, and our own bodies.” Caulfield notes that his work has a whimsical, absurd quality. But it is also sombre, reflecting, as he says, “the sense of hope and anxiety that society often feels in relation to the possible impacts of new technology.”

Overcoming our historical tension between science and the humanities requires finding common ground to talk about it. As the late American biologist and political activist Barry Commoner argued, a healthy democracy requires science to engage with the public, laying out facts that allow us to make informed political choices. Science must be a conversation, conducted in a language understood by all.

Photo: Shutterstock by ESB Professional