Mexico is the world’s 10th largest oil producer, and its state-owned oil company, Petroleós Mexicanos (Pemex), is the world’s 8th largest company in terms of production. As is the case in other Latin American countries such as Venezuela and Brazil, the oil sector accounts for a significant share (6 percent of GDP) of the economy in Mexico. As a result, the country has been hit especially hard by the global downturn in oil prices. Mexico’s oil production is currently at 2.2 million barrels per day (bpd), down from over 3.4 million bpd a decade ago. This puts current production at its lowest level in over 30 years (figure 1).

More than half of Mexico’s oil production comes from two offshore fields — Ku-Maloob-Zaap and Cantarell. The majority of this offshore oil is sold as heavy “Maya” crude oil which competes for market share in the United States Gulf Coast (USGC) with Western Canadian Select (WCS) and Venezuela’s Orinoco. Mexico and Venezuela are the main heavy crude oil suppliers to the USGC, accounting for over 45 percent of the refining hub’s imports total crude oil imports (or 1.5 million bpd of 3.2 million bpd imported to Gulf Coast refineries in 2015).

Over the past decade, heavy crude imports to the USGC from Mexico have decreased nearly a million barrels per day as a result of declining reservoirs, insufficient upstream investment and declining oil prices. This has led to speculation that Canadian heavy crude oil might be able to increase its market share in the USGC. Unlike Venezuela, however, Mexico has undertaken significant steps to attract foreign investment, to develop new plays (including offshore fields containing oil similar to Canada’s), and to reinvest in its oil production. These moves will improve Mexico’s long-term competitive positioning in the USGC and make it harder for Canada to displace Mexico in the Gulf.

Mexico and Pemex

Mexico’s history as an oil producer dates back to 1869, when the first Mexican oil well was drilled. However, commercial production did not start until 1901, at which point major US and UK oil companies essential took control of the country’s oil reserves for nearly 40 years. As a result of labour disputes and broader social issues surrounding the international exploitation of the country’s resources, Mexico nationalized the industry in 1938, creating Petróleos Mexicanos, better known as Pemex.

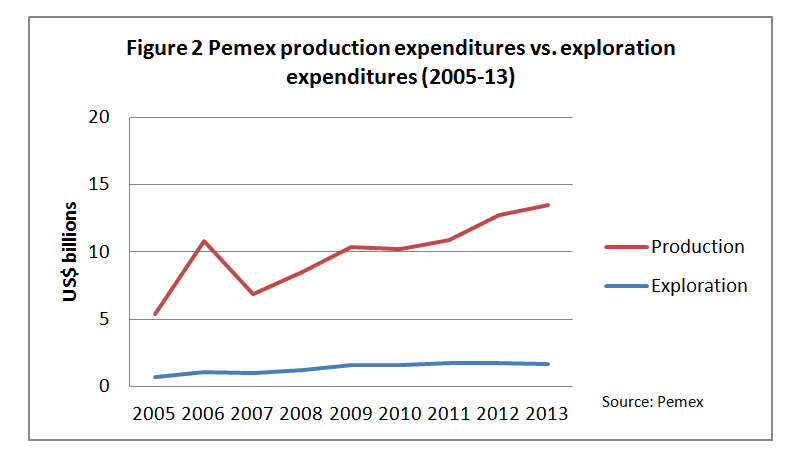

For years, Pemex has sustained itself on its easily exploitable shallow water fields, without investing the exploration capital necessary to develop more challenging reserves that are the source of future growth. According to Pemex annual reports (2005-13), production expenditures increased from just over US$5 billion in 2005 to approximately US$14 billion in 2013, while exploration expenditures were constant within the US$1.5-1.7 billion range over the same period of time (figure 2). In comparison, in 2006 Saudi Aramco was already spending nearly US$3 billion on exploration, while Shell spent nearly US$2 billion. Furthermore, Exxon increased its exploration costs by approximately US$1 billion between 2001 and 2010.

Many analysts point to Mexico’s dependence on easily recoverable oil reserves, and its lack of exploration and infrastructure spending, as the main factors contributing to the declines in production. This, in addition to the current financial situation at Pemex, has prompted the country to pursue Energy Market Reforms.

Pemex is severely in debt; in the near term the company faces as much as US$11.7 billion of debt maturities in 2017. Overall, Pemex has nearly US$90 billion in debt and owes more than US$5.5 billion to service providers. Under President Enrique Peña Nieto, Mexico plans to make historic changes to its energy sector, in an attempt to reverse the recent production declines and solve Pemex’s debt situation.

Constitutional reform

On December 20, 2013, President Peña Nieto implemented constitutional reforms related to Mexico’s energy sector, with the intent of increasing foreign investment and reversing the country’s production declines. On August 11, 2014, these reforms were officially implemented, opening Mexico’s energy sector to private investment for the first time in over 75 years. As a result, Pemex can now enter into joint operations with international companies that have the experience, technology and capital needed in order to develop some of Mexico’s harder to access reserves, particularly deep-water offshore reserves.

In August 2014, the US Energy Information Administration (EIA) said that it would be increasing its long-term Mexican crude oil production forecast by 75 percent. Initially the EIA pegged Mexican production to decrease to 1.8 million bpd by 2025 before recovering slightly to 2.1 million bpd by 2040. However, the EIA now expects Mexican oil production to surpass 3 million bpd by 2025 and be as high as 3.7 million barrels per day by 2040.

Auctioning of assets

In December 2014, shortly after implementing the reforms, Mexico initiated its first round of public bidding on some of its offshore exploration blocks. While only 2 of the 14 blocks available were awarded to successful bidders in phase 1, phase 2 resulted in awarding 3 out of 5 production blocks, while phase 3 resulted in another 25 onshore blocks, located throughout the country, being sold.

Mexico will auction 10 offshore fields for exploration and development in the Gulf of Mexico on December 5, 2016, which will require an investment of $4.4 billion during the life of the contract for each field. According to a report by Wood MacKenzie, a number of blocks being offered by Pemex contain large extra-heavy oil reserves. Given that only 11 percent of the oil contained in these reserves is recoverable, Wood MacKenzie analysts expect heavy and extra-heavy oil specialists to be particularly interested in these opportunities. It has been estimated that Mexico’s offshore blocks could contain between 1-2.5 billion barrels of heavy oil. Furthermore, in a 2012 investor presentation, Pemex outlined its intent to invest in and develop more extra-heavy resources, particularly in the southern portion of the Salina del Istmo province. So far, Mexico has secured US$7-8 billion in foreign investments through these auctions.

Debt restructuring

Although Pemex is severely in debt, recent steps may allow the company to weather the low oil price scenario more easily and continue producing oil. For example, in April 2016, the Mexican government gave Pemex a US$1.5 billion tax break, plus another US$4.2 billion, to help pay contractors. In return for the aid, Pemex must slash its debt by the same amount, stick to a previously announced US$5.4 billion austerity strategy, and develop debt management plans. The deal also involved a bond swap: the Mexican government said part of a US$2.7 billion bond issued to Pemex last year by the federal government would be swapped during the year for US$2.5 billion in federal government cash. Pemex also received a US$822 million credit line from a consortium of private Mexican banks, which can be put toward debt repayments.

Implications for Canada

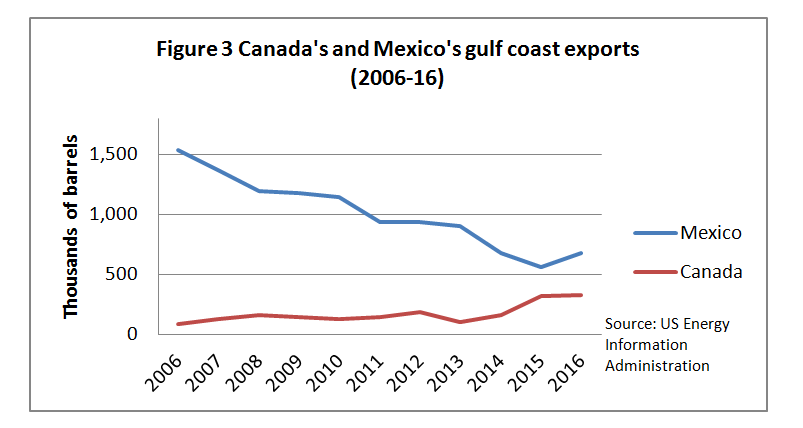

Though Mexican exports into the USGC have remained relatively stable in the past two to three years, they have fallen by nearly 1 million bpd from 2006. In April 2016, Mexico exported 677,000 bpd to the USGC down from 1.537 million bpd in April 2006. In contrast, Canada increased its exports to the USGC to 331,000 bpd in April 2016, up from 90,000 bpd a decade ago. However, two factors are hindering Canada’s ability to grow its market share in the USGC: pipeline capacity and rail costs (figure 3).

Canada’s ability to significantly increase its USGC exports depends on the development of new pipeline projects that allow easy movement between western Canada and the USGC. Furthermore, shipment by rail, which has been cited as a possible method of increasing exports, is too costly, particularly when oil prices and differentials between WCS and Maya are so low, (transporting crude by rail costs approximately US$10 more per barrel than the US$12 per barrel it costs to ship WCS via pipeline to the USGC.)

In the absence of new pipeline construction, Canada is limited in its ability to capitalize on the decline in Mexican exports to the USGC. However, many Canadian oil and gas companies and oilfield equipment and service providers may be able to capitalize on Mexico’s new openness to foreign companies participating in its oil and gas sector.

As far as what might happen in Mexico, it appears the country is determined to make major energy sector reforms, with the intent of increasing foreign investment and raising production and exports. If Mexico can increase its production, particularly its extra-heavy crude production, it will be well positioned to grow its share in the USGC, given its existing heavy offshore infrastructure and the fact that ramping up exports is not dependent on pipelines. The same cannot be said for Canada.

Photo: Anton Watman/Shutterstock.com

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.