We are entering a new global normal. Things will not be as they were. What is emerging is a new multipolar world: economic power is being dramatically redistributed; political, military and technological power will follow.

The international economic geography is shifting to Asia and other dynamic emerging economies. The demographics of aging is creating a global talent hunt. The digital universe is transforming what markets mean, and how social interaction and communication take place. There has been a dramatic decline of trust in leadership — whether political, corporate, regulatory or moral — due to the cumulative impact of financial, environmental, corporate governance and regulatory crises.

In such a world, the drivers of success are also shifting. In a global marketplace, it takes a global perspective and a capacity to serve markets that transcend traditional boundaries. In highly competitive markets, it is the ability to attract talent and to drive competitiveness through faster innovation and stronger productivity. In a more volatile world, stable and trusted institutions and sound fundamentals create national advantage.

How is Canada placed in this new global normal? This is our second annual look at Canada and its relative position in the world. While much has happened in the world this year, much has also remained the same. The slow, sloggy recovery continues in advanced economies, the European debt crisis is still with us, food prices continue to rise rapidly in a number of emerging economies, and deleveraging has not yet run its course in the US and Europe.

Canada has a lot going for it. It withstood the financial crisis better than most other countries, and it has continued to be a leader in financial stability during the ongoing aftershocks. During this time of slow, volatile and uneven global recovery, we have a distinctly Canadian story to share with the rest of world. Our relative global strengths include the following:

- solid macroeconomic policies — low inflation and fiscal probity,

- a diversified, sophisticated economy,

- robust resources — natural and human, and

- a sound financial system with strong financial institutions.

A country’s relative position with respect to a broad range of economic, fiscal, financial, social and institutional factors conveys a fulsome sense of its current progress and its future capability. It is in that context that this article presents a 2011 global snapshot of Canada, in conjunction with Policy Options’ 2011 Year in Review.

We enter the global competitive race with real strengths: world-class macroeconomic fundamentals and a national consensus to maintain them; enormous natural resources and a secure, market-based system to develop them; a multicultural society that reflects the emerging economy in which we need to trade and prosper; as well as strong institutions and effective social safety nets in a world where trust is declining and income disparities are high in a number of countries.

With our myriad of relative advantages, a lack of urgency may be our biggest risk. We need to build on our many strengths, not rest on them. And we need to tackle our weaknesses, the most pressing and pervasive of which are our underperformance in productivity and innovation.

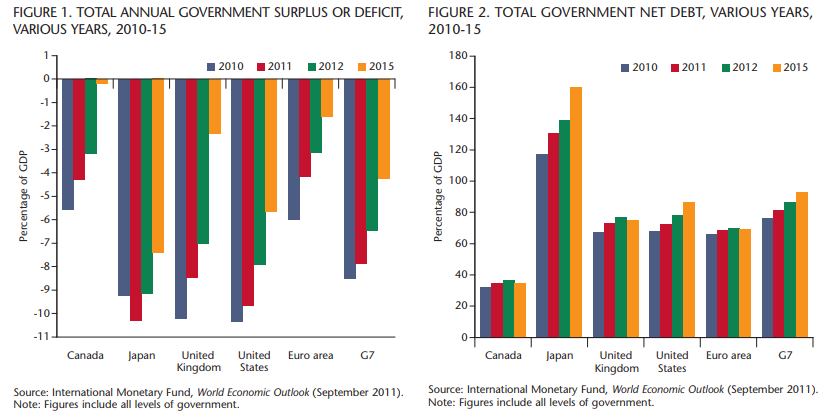

One clear strength is our solid fiscal position. The budget deficit on a total government basis (as a percent of GDP) is low relative to most G7 countries. Net debt as a percent of GDP for Canada in 2011 is projected to be 34.9 percent, well below that of the US and all other G7 countries (figure 1). Looking ahead, the International Monetary Fund expects that our net debt as a share of the economy will be less than half those of the US and the EU by 2015 (figure 2).

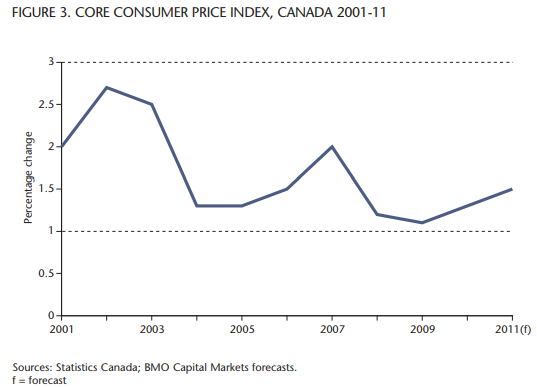

Low inflation is the result of Canada’s effective inflation-targeting monetary policy. The target range is 1 to 3 percent, with the Bank of Canada’s aim keeping core inflation at the 2 percent target midpoint, on average, something that it has successfully done for more than a decade (figure 3). In 1991, Canada led the G7 in adopting an inflation rate target, a policy now used by over two dozen central banks around the world.

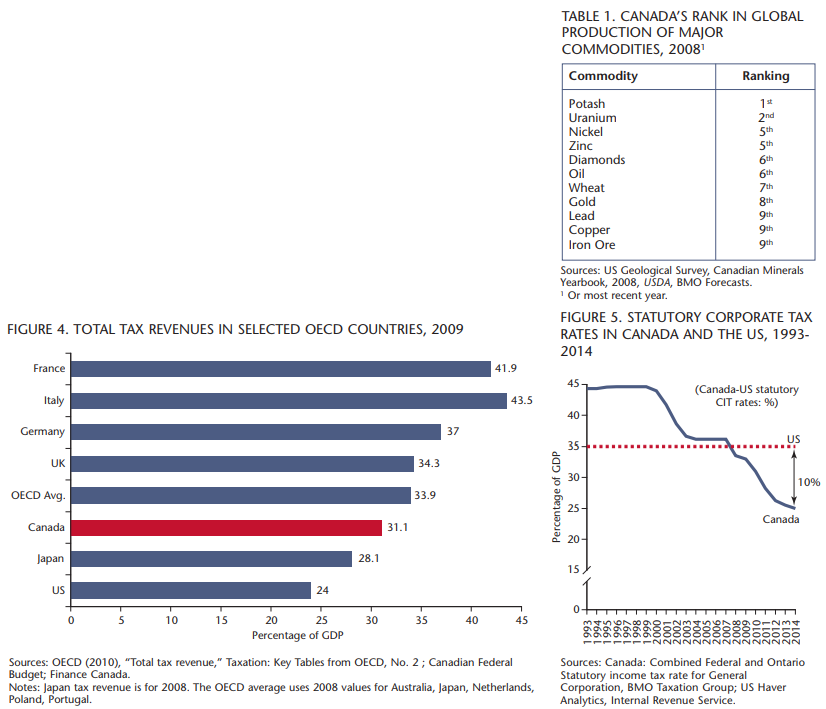

Canadian tax rates in total are now below both the OECD and G7 averages. Lower taxes, particularly on capital and companies, improve business competitiveness, growth and job creation, and encourage investment in Canada by Canadians and non-Canadians alike. Corporate income taxes in Canada are 10 percentage points lower than those in the US, a remarkable change from Canada’s pre-2000 corporate tax regime (figures 4 and 5).

Canada is a diversified and sophisticated economy, quite different from its traditional image. Reflecting this diversification, over the past decade Canada’s largest growth came from the service, retail, scientific and technical sectors. Canada is the fifth largest aerospace producer; the third largest exporter of automotive products; and a leader in some areas of bio-technology, medical devices, biopharma and digital media.

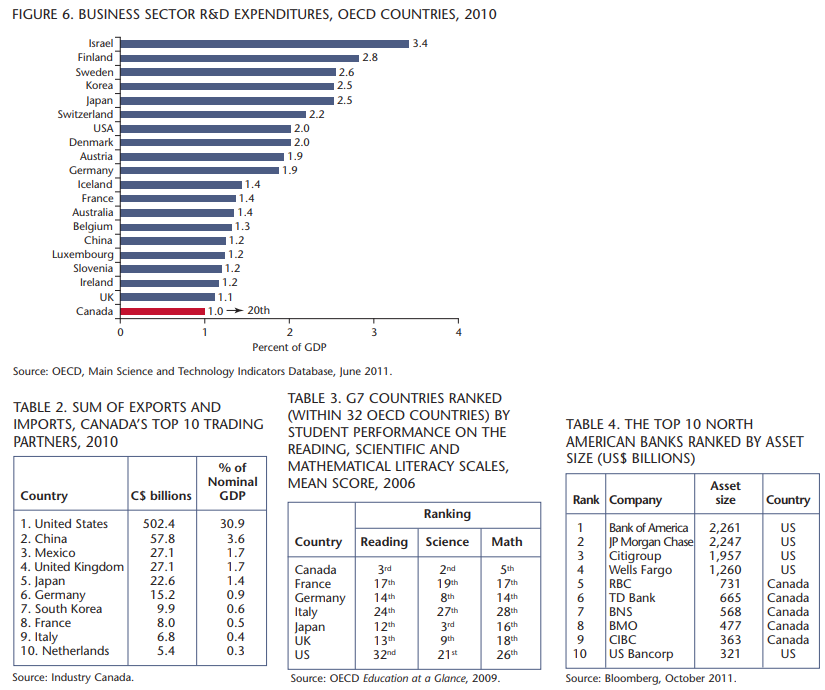

These results aside, we continue to have broad-based innovation and productivity deficits. Over the last decade, the Canadian dollar appreciated 42 percent against the US dollar, while our productivity growth averaged less than 1 percent annually, well below that of the US. While our university research capabilities are strong, our business sector’s innovation performance is poor. Indeed, Canada now ranks 20th among OECD countries in business sector R&D spending as a percentage of GDP (figure 6). We need to shift most sectors of our economy further up the value-added chain through innovation in products, markets and processes. This will be critical to maintaining and building on Canada’s competitive advantages.

Canada is a global power in the commodities the world wants and needs. As world demand for natural resources grows in line with rapid Asian expansion, this clearly benefits Canada. For example, Canada is the world’s largest potash producer, the world’s second largest uranium producer, a major energy producer with the second largest oil reserves in the world, and a large producer of agricultural products like wheat, canola, barley and lentils (table 1).

Canada trades with a diverse group of partners (table 2). This trade is highly concentrated in trade with the largest and richest market in the world, the US. However, market opportunities are shifting away from the mature Western economies and toward the dynamic emerging economies of Asia and South America. Seventy-five percent of Canadian exports go to the United States, while just over 3 percent reach China and less than 1 percent each go to South Korea, Brazil, India, Taiwan, South Africa and Russia, to name a few (all of which are growing at multiples of the US economy). China, India and Brazil alone account for almost 40 percent of the world’s population, have rapidly growing middle classes (larger than North America’s), and are markets for only not our commodities but also our value-added foodstuffs, housing materials, education services, health care, technology, and much more.

In a knowledge-based economy, talent is a creator of competitive advantage and a driver of success. As Finance Minister Jim Flaherty recently noted in a Policy Options interview (November 2011), “Our greatest renewable resource is our grey matter.” Canada has a relatively strong education system. Indeed, on standardized reading, scientific and mathematical literacy scales, Canada ranks third, second and fifth, respectively, among OECD countries —well ahead of the US (table 3). Canada’s workforce is well educated, skilled and very multicultural. With the globalization of markets and economies, this diverse, multilingual and multicultural talent base is a strategic advantage for Canada and Canadian companies.

For the fourth consecutive year, the World Economic Forum has cited Canada as having the soundest financial system in the world. And for the past two years Moody’s Investor Services has ranked Canada’s banking system first in the world for financial strength. Canada was the only G7 nation whose banks did not require a government bailout during the global financial crisis. Since then, Canadian banks have continued to grow, particularly compared with their American counterparts. Today, five of the major Canadian banks rank among the top ten financial institutions in North America, based on asset size (table 4).

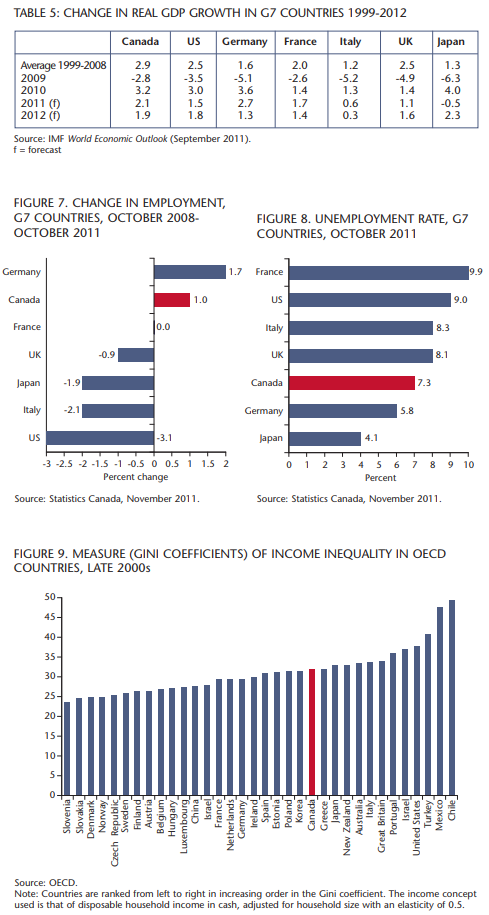

The recession of 2009 impacted Canada less severely than the other G7 countries; the Canadian economy experienced the smallest decline in real GDP among the group. Just as Canada led the G7 countries in growth over the decade before the global recession, the IMF predicts we will continue to lead G7 growth in the recovery through 2012 (table 5).

Canada’s labour market has recovered all of the jobs lost during the recession and then some (figure 7), in sharp contrast to the US. We also have a much lower unemployment rate than does the US, which is very different from past cycles (figure 8). And Canada was the only G7 country that did not experience a decline in its wealth-to-income ratio. While wealth per adult in the United States is still 8 percent below the 2007 level, Canada’s wealth in domestic currency is now 3 percent above the 2007 level.

For a country, wealth accumulation and wealth distribution both matter. The most common measure of income disparity is the Gini coefficient, compiled by the OECD (figure 9). Income inequality is becoming an issue both for highly developed countries like the US and for rapidly developing counties like Brazil and Mexico. While the income disparity is much less in Canada than in the US, it has risen in recent years. This is a development that deserves careful scrutiny.

Where does all this take us? The new global reality is a two-speed world, with a global recovery that will be longer, slower and more volatile in Western economies than they have experienced in decades. In this new global reality, Canada ranks among the top 10 world economies on the main global competitiveness rankings in 2011. On the UN Human Development index, we stand 8th, and on corporate governance, 2nd. Not bad at all.

Canadians should take pride in our 2011 relative performance, but we should not be complacent. We need to tackle our productivity underperformance, improve our innovation results, and broaden and deepen our economic ties with key emerging markets. Most importantly, we must never lose sight of the fact that we are in a global competitiveness marathon, year after year after year, and we must plan and act accordingly.

Photo: Shutterstock