Late on the night of May 2 as election results from across Canada poured in, veteran observers of the Canadian political scene were greeted with two sights most probably never expected to see in their lifetimes. Not only did the New Democratic Party win 103 seats to vault ahead of the Liberal Party and become the official opposition in Canada’s Parliament, but the driving force behind the NDP’s success was an unprecedented surge (dubbed the “orange crush”) of support in the province of Quebec, traditionally an electoral wasteland for the NDP. The NDP went from having one seat in Quebec at dissolution to having 59 seats out of 75, turning the seemingly invincible Bloc Québécois into road-kill and almost wiping the Liberal and Conservative parties off the electoral map as well.

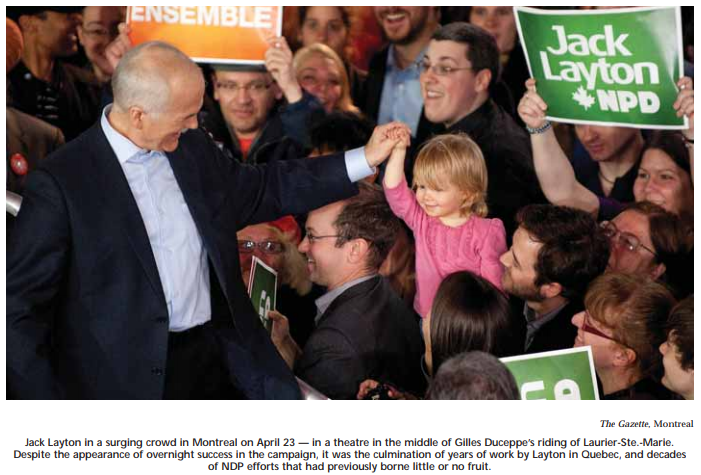

Much has already been written about NDP Leader Jack Layton’s personal popularity with Quebecers and about the impact of events and turning points of the 2011 election campaign in Quebec such as Layton’s appearance on the popular Sunday-night TV show Tout le monde en parle and the French leaders’ debate. Some commentators have tried to dismiss the NDP success in Quebec either as a fluke or as being purely the result of Layton’s charisma. In reality, this election was the culmination of a long tale of mutual flirtation between Quebec and the NDP that goes back over 40 years — a flirtation that came very close to being consummated on at least two previous occasions.

What is most surprising about the NDP sweep of Quebec is not that it happened but rather that it took so long to happen. The social and cultural values of most Quebecers and their views on most public policy issues have long been in sync with the NDP’s social democratic ideology and postmodern stances on various moral and social issues. A strong case could be made that in 2011 there is a far better policy and values match between the NDP and Quebecers than there is currently between the NDP and the people of Saskatchewan — the birthplace of the party! Research has shown that Quebecers have a much more collectivist attitude toward society and tend to be more supportive of “big government” than any other Canadians. At the provincial level, both the Parti Québecois and to a lesser extent the Quebec Liberal Party would be considered quite social democratic by pan-Canadian standards. It is no coincidence that Thomas Mulcair — Jack Layton’s deputy leader — came to the NDP after having been a cabinet minister in the Quebec Liberal provincial administration.

Prior to the NDP’s founding in 1961, its predecessor the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) had never had any real following in Quebec — despite the valiant efforts of leader Thérèse Casgrain, a feminist well ahead of her time. A party founded by Protestant clergy from the prairies preaching the social gospel was too culturally alien, and the fact that the CCF was explicitly “socialist” led to denunciations from the pulpit in Duplessis-era Quebec. There may have been a natural affinity even then between the CCF’s collectivism and Quebec, but this was a mismatch in an era when society was still polarized along Catholic versus Protestant lines.

Some commentators have tried to dismiss the NDP success in Quebec either as a fluke or as being purely the result of Layton’s charisma. In reality, this election was the culmination of a long tale of mutual flirtation between Quebec and the NDP that goes back over 40 years — a flirtation that came very close to being consummated on at least two previous occasions.

The first big date between the NDP and Quebec came in the mid-1960s. After the NDP was founded, the dream was that the new party would shed its “hayseed” image and build bridges with the labour movement and other progressive elements in Quebec. This was the time of the Quiet Revolution in Quebec, and the Lesage provincial government was embarking on an ambitious social democratic agenda of expansion of social programs, secularization and nationalization of hydro-electric power. Federally, the NDP staked out some policy stances that were coincidentally popular in Quebec, such as opposition to the deployment of nuclear warheads in Canada and support for the creation of medicare. The NDP began to make inroads among public intellectuals in Quebec. It’s a well-known piece of Canadian political folklore that in the 1963 election Professor Charles Taylor ran for the NDP in Mount Royal and that one of his campaign workers was his good friend and fellow professor Pierre Elliott Trudeau, who had denounced Lester Pearson as a “defrocked prince of peace” in the pages of Cité libre for his decision before the 1963 campaign to reverse Liberal Party policy and accept Bomarc missiles armed with nuclear weapons on Canadian soil.

Back in those days, there was little or no expectation that Anglo-Canadian politicians would be bilingual — and the NDP’s Tommy Douglas was as unilingually anglophone as his rivals Lester Pearson and John Diefenbaker. Douglas, however, was open to the newly emerging aspirations of Quebec in the 1960s, and under his leadership the NDP welcomed many Quebec nationalists to its ranks; and the NDP was the first federal party to embrace the “deux nations” theory of Confederation, which was a precursor to the later discussions of asymmetrical federalism and special status for Quebec that dominated constitutional debate in the subsequent decades. Douglas also managed to recruit a Quebec leader by the name of Robert Cliche who turned out to be a charismatic and highly respected figure. Cliche was a law professor from the Beauce region of Quebec (ironically, Beauce is now noted for its conservatism and for being the personal fiefdom of the libertarian once and future cabinet minister Maxime Bernier) and began attracting more and more support to the NDP in the mid-1960s.

That was a time when a political vacuum appeared to be opening up in Quebec. For soft nationalists and intellectuals and opinion leaders, the Conservatives under Diefenbaker were not an option, the Liberals were bogged down with endless scandals and Réal Caouette’s reactionary Créditiste phenomenon was fading fast. In the 1965 election, the NDP recruited some notable candidates and came close to winning in several Quebec ridings. Little did anyone know at the time that Pierre Trudeau’s switch to the Liberals and his win over Charles Taylor in Mount Royal that year would set in motion a chain of events that would cause the NDP to crash on the launching pad in Quebec three years later. The mid-1960s were a good time to be a New Democrat in Quebec. The party’s openness to special status for Quebec (a policy also adopted by the federal Progressive Conservatives of that era) was getting noticed, and the NDP started assembling a dream team of candidates for the next election including Cliche, CBC host (later a Liberal senator) Laurier LaPierre, Charles Taylor and others, and was being taken increasingly seriously. In an interesting foreshadowing of events over 40 years later, there was even a byelection in 1967 in Outremont, where the NDP candidate, Denis Lazure lost quite narrowly. The new Union Nationale administration of Daniel Johnson was at loggerheads with the centralizing tendencies of the federal Liberals and their combative justice minister, Trudeau. Johnson was looking to hedge his bets by supporting non-Liberal candidates at the federal level and in some ridings this meant quietly backing the NDP.

The first flirtation between the NDP and the voters of Quebec seemed to show potential — but then Quebec (along with the rest of Canada) was swept off its feet by another suitor, Pierre Elliott Trudeau. Needless to say, Trudeau’s centralizing “One Canada” vision of federalism left no room for the asymmetrical federalism proposals involving special status for Quebec coming out of both the NDP and the Progressive Conservatives. The newly burgeoning Quebec independence movement also had little interest in anything that smacked of “renewed federalism.” As was to be the case 20 years later, when federal politics in Quebec gets polarized around the “national question” it tends to suck every bit of oxygen out of the room and to shut down any discussion of any other issue. The last thing the Liberal Party needed in Quebec was any competition beyond Réal Caouette, and at the time there was speculation that if Robert Cliche were to be elected to Parliament, he might be a potential successor to Tommy Douglas. The Liberals enticed a very popular former provincial Liberal cabinet minister, Eric Kierans, to run against Cliche in a suburban Montreal riding. Cliche’s fate (and that of most other non-Liberals in Quebec) was sealed the day before the 1968 election, which happened to coincide with the Saint-Jean-Baptiste Day parade in Montreal. A crowd of separatist demonstrators hurled bottles and debris at the review stand, and while everyone else ducked for cover, Trudeau didn’t flinch. This image was on the front page of every newspaper in Canada as people went to the polls. Kierans defeated Cliche by a narrow margin, while the rest of the NDP all-star cast of candidates in Quebec that year went down like ninepins.

Cliche quit as Quebec NDP leader, became a judge and later headed up the high-profile Cliche commission on corruption in the construction unions in Quebec. One of his two co-commissioners also made a name for himself: a Montreal-based Tory “backroom boy” by the name of Brian Mulroney. Ironically, Eric Kierans — the man who singlehandedly snuffed out the NDP’s great hope for a Quebec breakthrough — lasted two years as a Liberal cabinet minister before having a falling-out with Trudeau and quitting politics. He also announced during the 1972 election campaign that he was voting NDP and even considered running for the federal NDP leadership in 1975.

Throughout the 1970s Trudeau and the Liberal Party were such a proverbial “elephant in the room” as far as federal politics in Quebec was concerned that it was almost impossible for any other voice to be heard. There was some fanciful speculation in the NDP in the early ”˜70s that the 25 to 30 percent of Quebecers who were voting for the Parti Québécois might be enticed to vote for the federal NDP since both parties had a social democratic orientation. David Lewis was also the first CCF-NDP leader who could speak any French whatsoever! The PQ had no interest in shoring up the NDP in Quebec, and in 1972 René Lévesque campaigned across Quebec urging Quebecers to abstain from casting a vote in Canadian elections.

The rest of the 1970s and early 1980s was a time of hibernation for the NDP in Quebec. When Ed Broadbent became leader in 1975, he spoke almost no French at all, and even if he had, it probably would not have made much difference. Politics in Quebec, after the 1976 provincial election brought the PQ to power, was almost totally subsumed by the “clash of the titans” between Trudeau and Lévesque. Virtually the entire progressive civil society in Quebec — unions, social movements, the major cultural and intellectual figures, in other words all the people who would have been the natural constituency of the NDP — gravitated toward the PQ and to the nationalist movement. The NDP was simply irrelevant to the great debate in Quebec in the 1970s and also fell victim to a stereotype among some Quebecers of being seen as “centralizing.” For Quebecers who saw themselves as progressive and yet also federalist and in favour of a strong federal role, Trudeau’s Liberals were a perfectly good alternative. Meanwhile Quebecers elected the PQ to two consecutive majority governments when it ran on a distinctly left-of-centre social democratic platform. New Democrats could only press their faces against the glass window of the candy shop called Quebec and watch while René Lévesque made off with all the candy.

Any time that a political vacuum had been created in Quebec, there was always the possibility that the NDP could fill it. The story of the repatriation of the Constitution in 1982 and the subsequent decline and fall of the federal Liberals in francophone Quebec has been told many times. Once Trudeau retired in 1984, the NDP was weakened by internal divisions around the constitutional debates and felt that it had to “save the furniture” in English Canada in the face of the Tory juggernaut under Mulroney. Much has been written about how pivotal the first-ever French leaders’ debate was in 1984 and how the fluently bilingual, Quebec-born Mulroney made mincemeat out of John Turner, whose French language skills proved to be overrated. What is less well-known is that Ed Broadbent had been brushing up on his French and spending a lot of time in Quebec. He was willing and able to take part in the French debate and got some credit for making the effort.

The mid-1980s were the second period when it seemed like everything suddenly moved into place for a major NDP breakthrough. Quebecers quickly became disillusioned with the Conservatives, and the Liberals were still stigmatized by the constitutional wars of the early 1980s. The Meech Lake Accord seemed like a solution to the “national question” and was quickly endorsed by the NDP. The Conservatives had swept Quebec in 1984 but had very shallow roots in the province. Every time

A strong case could be made that in 2011 there is a far better policy and values match between the NDP and Quebecers than there is currently between the NDP and the people of Saskatchewan — the birthplace of the party! Research has shown that Quebecers have a much more collectivist attitude toward society and tend to be more supportive of “big government” than any other Canadians.

Mulroney brought in policies to placate his small-c conservative base in western Canada, it was a vote loser in Quebec and vice-versa. Quebecers were starting to warm to Ed Broadbent. He spoke French with about as thick an accent as Jean Chrétien had speaking English, and that seemed to add to his charm. In the mid-1980s there was a period when the NDP not only flirted with being the lead party across Canada in national public opinion polls, but was consistently polling at what were considered stratospheric levels for the NDP in Quebec.

In many ways for the NDP the leadup to the 1988 federal election in Quebec was the exact reverse of the lead-up to the 2011 election. The party was polling at high levels when the election was called and was taken very seriously by its opponents. Ed Broadbent in 1988, like Jack Layton in more recent times, seemed to be riding a wave of personal popularity in Quebec. However, once again this flirtation did not bear fruit. In the late 1960s, the NDP was side-swiped by the national question in Quebec. In 1988 the NDP fell victim to another highly polarizing issue in Quebec — the free trade agreement with the US. For a variety of reasons free trade with the US was very popular in Quebec, and while left-wing civil society tended to passionately oppose free trade in English Canada, in Quebec this was not the case at all. The PQ even went from covertly cheering on the NDP to openly providing organizational support to Mulroney’s Tories. The Tories swept Quebec and the NDP was left with no seats at all despite a record 14.4 percent of the popular vote in the province. Broadbent quit as NDP leader, and his failure to make a breakthrough in Quebec was probably the biggest disappointment of his political career.

Despite the letdown of the 1988 election, the NDP had established some infrastructure and was still showing signs of life in Quebec. As late as 1990, while the Meech Lake Accord was on its final death march, Phil Edmonston of the NDP won a by-election in Chambly with 70 percent of the vote, becoming the first NDP MP ever from Quebec. However, once again the NDP had the rug pulled out from under it in Quebec. In the wake of the collapse of the Meech Lake Accord, the Bloc Québécois was created and that party very quickly siphoned away virtually all of what was left of the NDP’s support in Quebec. In some ways, for the NDP it was like being in a casino for hours, pumping coin after coin into a slot machine, then walking away only to see someone else put in one coin, pull the lever and have a cascade of coins fall into their lap.

The 1990s was a very dark period for the federal NDP all across Canada, and Quebec was the least of its worries. The party chose two consecutive leaders, Audrey McLaughlin and Alexa McDonough, who spoke little French and had little understanding of Quebec sensibilities. As long as the BQ was giving voice to Quebecers’ progressive sentiments on social and economic issues, there was really no reason for Quebecers to look to the NDP, which was barely holding onto official party status. In the 2000 federal election, the NDP took just over 1 percent of the vote in Quebec, and in many ridings NDP candidates received fewer votes than did candidates running for the Natural Law Party or the Marijuana Party. Under Gilles Duceppe the BQ had moved far from its origins as a party of renegade Tories and was now a clearly left-wing party with positions on most issues that were indistinguishable from those of the NDP.

Throughout this period, it should be noted that Quebecers never exhibited a negative attitude toward the NDP. It was simply not on the radar screen. Alexa McDonough had reasonable approval ratings in Quebec — to the extent that people knew enough about her to form an opinion. In 2002, before Jack Layton had even become leader, Environics polling showed some unexpected bumps in NDP numbers in Quebec. In the early 2000s more and more issues on which the NDP took positions that were popular in Quebec took centre stage in Canada. On social issues such as same-sex marriage and abortion rights, Quebecers as a whole tended to be very socially liberal and on the same page as the NDP. The same could be said for the NDP approach to environmental issues. The NDP’s opposition to the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan outflanked the BQ and also began to attract some attention. Research has shown that antipathy toward George W. Bush and toward American foreign policy in general was more intense in Quebec than anywhere else in Canada.

When Jack Layton decided to run for the federal NDP leadership in 2002, creating “winning conditions” for the NDP in Quebec was not at all central to his campaign. Although Layton had grown up in Montreal and his father and grandfather had been politicians in Quebec, he had lived in Toronto since the early 1970s and his entire political career had been forged in Toronto municipal politics. His Quebec roots were not well-known or promoted among the party rank and file. Though Layton had learned French in his youth, after 30 years in Toronto and after having married into a Chinese-Canadian family, he may have had greater fluency in Cantonese than he did in French when he launched his candidacy. The NDP elects its leader through a straight one-member one-vote process with no weighting by province or by riding. There were more card-carrying NDP members in some provincial riding associations in Saskatchewan at that time than there were in all of Quebec. The main thrust of Layton’s leadership campaign revolved around his ability to reestablish the NDP in Canada’s urban centres by leveraging his background in municipal politics, by strengthening links between the NDP and progressive social movements and by emphasizing environmental and social issues. To most New Democrats, this meant winning more seats in Toronto and Vancouver — with the idea of winning seats in Montreal still a long-term fantasy. What few NDP members there were in Quebec mostly supported Layton, given that he was more bilingual than the other major candidates, and he had taken stands on issues like the Clarity Act and on asymmetrical federalism that were more in line with mainstream “soft nationalist” opinion in Quebec.

The first priority for the NDP in the 2004 and 2006 elections was to reestablish a presence in traditional areas of strength in English Canada. As a result little money or resources were devoted to Quebec in those campaigns. Federal politics in Quebec was dominated by news of the sponsorship scandal — an issue tailormade for the Bloc Québécois. However, making a breakthrough in Quebec was always a longer-term priority of Layton’s. He knew that making the NDP the second choice of BQ supporters would put the NDP in a strong position when the BQ declined. When the NDP commissioned research in the lead-up to the 2004 election, they were pleasantly surprised by how positively voters in Montreal reacted to Layton and to the NDP as a party. The main obstacle to getting more support in Quebec was simply a perceived lack of viability. The NDP had no representation in Quebec, had no spokespeople of any note and was simply not taken seriously. No one would “waste” their vote on a party that was perceived as not being competitive and as having no chance, particularly in a polarized duopoly where the conventional wisdom was that federalists would all vote Liberal and nationalists of any hue would all vote BQ.

Nonetheless, initial steps were taken and NDP support in Quebec inched up from 1 percent in 2000 to 5 percent in 2004 to 8 percent in 2006. In the summer of 2006 Layton, whose fluency in French had by that time vastly improved, made the strategic decision that the NDP would hold its federal convention in Quebec City, and this drew a fair amount of publicity in the francophone media. One of the keynote speakers was Thomas Mulcair, who had recently resigned from Jean Charest’s cabinet after a dispute over an environmental issue. Little did anyone know at the time that he would prove to be the spark that would light the orange flame.

For almost 50 years the NDP had always struggled against a jinx in Quebec of never having elected anyone at any level, and this always meant the party could never be seen as being viable. It was clear that the first step to making a pitch for votes in Quebec was to win something somewhere and to have at least one more high-profile spokesperson in the province in addition to Jack Layton. When Jean Lapierre, Paul Martin’s erstwhile Quebec lieutenant, resigned his seat a year after the Liberal defeat in January of 2006, Layton saw a golden opportunity. Despite having a reputation for being “the safest Liberal seat in Canada,” Outremont was actually the riding where the NDP had had its best showing in all of Quebec in 2006, and the Liberal vote had been in decline for several consecutive elections. There was a sizable BQ base in the riding — but Outremont had too large a nonfrancophone population to ever be winnable for the BQ. In many ways, the dynamics of the Outremont by-election proved to be a dress rehearsal for what happened across Quebec in the 2011 election.

In retrospect, the landslide NDP win in that by-election on September 17, 2007, was a far more pivotal event that anyone was willing to acknowledge at the time. Most of the commentary at the time quickly wrote off the NDP win as a fluke. There has long been a tendency among many political reporters in Canada to look at every political event through the lens of what it says about the Liberal Party. Therefore it came as little surprise when the morning after the byelection, the headline in the Globe and Mail was “Tories Steal Seat from Bloc as Liberals Lose Outremont” — one had to read the fine print to learn which party actually won in Outremont. As it turned out, the NDP was able to replicate the Outremont experience very effectively later on, decimating the BQ vote while also taking a slice of the Liberal vote. In some ways, the small Conservative breakthrough in Quebec in the 2006 election created some new synergies for the NDP since it opened the door to a left/right debate in a province where previously federal politics had been totally dominated by the federalist/sovereignist dichotomy. Once Stephen Harper’s Conservatives began to have ambitions in Quebec, they quickly jettisoned Reform Party positions on federalism and made gestures like recognizing Quebec as a “nation” and allowing Quebec to opt out of various federal provincial arrangements. This gave the NDP some cover for its own proposals on Quebec, described in the Sherbrooke Declaration.

The win in Outremont did not produce instant results, but it showed for the first time that NDP wins were possible in Quebec, and as a result in 2008 the NDP was able to recruit more credible candidates than ever before and ran a fully funded ad campaign in the province. Although the NDP failed to win any additional seats in 2008, Layton’s personal popularity advanced. NDP numbers also steadily rose in Quebec in the wake of the abortive coalition with the Liberals and BQ in December 2008, since Quebec was one place where the coalition had been very popular. Polling data from late 2009 through 2010 began to consistently show the NDP in the high teens even while BQ support was still high, and the fact that BQ voters kept naming the NDP as their second choice indicated a lot of potential. The data also showed that Layton’s personal popularity was getting higher and higher, to the point where he was routinely coming ahead of both Stephen Harper and Michael Ignatieff as most trusted federal leader and was closing in on Gilles Duceppe.

There had always been a belief that if the NDP could just get its foot in the door in Quebec, the proverbial dam could break. It almost happened when Quebec flirted with Robert Cliche in 1968 and it almost happened again with the brief love affair with Ed Broadbent in the mid-1980s. In 2011 the theory was finally put to the test. As it turned out, once Quebecers saw the NDP as a viable party that was positioned to win seats and be a major player, there was seemingly nothing to stop the NDP from racking up a sweep of Quebec that went beyond the party’s wildest dreams.

Under Jack Layton the love affair between Quebec and the NDP was finally consummated. Now the only question is whether this will be a long-term relationship. Some observers (particularly supporters of other parties) speculate that the rise of the NDP in Quebec will prove to be a one-night stand.

However, there are also reasons to believe that the NDP breakthrough in Quebec has a good chance of lasting a long time. In fact, the NDP may not have even reached its ceiling in Quebec in 2011. Even though the BQ was reduced to four seats, it still took 23 percent of the popular vote in Quebec. Those votes will be up for grabs in the next and future elections. All polling during the 2011 election campaign clearly indicated that the NDP was overwhelmingly the second choice of voters who stuck with the BQ. It is an open question whether the BQ will be on the ballot at all in the next federal election. It has lost official party status and all the funding and staffing that goes with that.

Quebec has just about the highest rate of unionization in Canada and attitudes toward the role of the state and social and environmental issues that are significantly to the left of those found in the rest of Canada. The remaining BQ vote, to the extent it’s on the left, may naturally migrate to the NDP in 2015. Meanwhile, there is work to be done by Jack Layton and the senior members of his team — managing expectations, especially in Quebec, as well as obvious caucus management issues around the nearly two-thirds of his caucus who have no prior experience in Parliament.

The good news for Layton and the NDP is that they have four years in front of them, as the official opposition.

Photo: meunierd / Shutterstock