The Polimeter is an online application created in 2011 by a team of political scientists at Laval University to monitor the fulfillment of campaign promises in Canada and Quebec. Our objective is to produce reliable, freely accessible data for peer-reviewed publications and for knowledge dissemination and public outreach.

The Polimeter rates each campaign promise as “kept”, “kept in part or in the works”, “broken”, or “not yet rated.” Each rating is supported by a citation drawn from government press releases, government bills, other official public documents or media sources. (Click here to access the Trudeau Polimeter and here to access the Couillard Polimeter. Click here to access the archived Harper Polimeter and here to access the Marois Polimeter).

During the federal election of October 2015, the Liberal platform promised to deliver on 353 specific policy pledges over the next four years. In the wake of the first anniversary of that election, it is a good time to assess which pledges have already been fulfilled. To this end, the Trudeau Polimeter has tracked each Liberal promise to measure its level of fulfillment. By comparing Trudeau’s performance with that of previous governments at the same stage, we try to evaluate the chances that pledges not yet rated will be fulfilled before the next election.

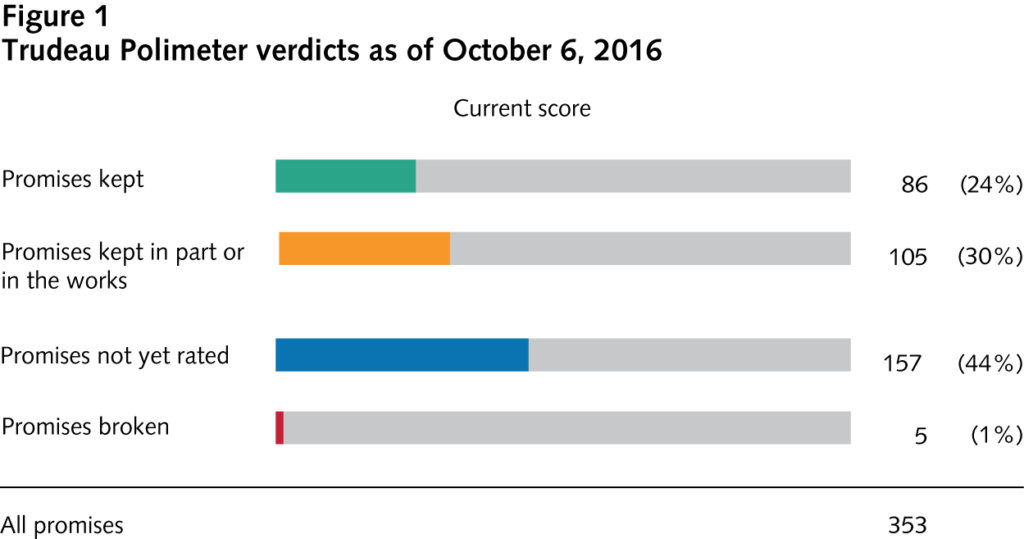

By early October 2016, 24 percent of the Liberal campaign promises have been “kept entirely” (Figure 1). Several promises in that category, such as the commitment to achieve an equal number of women and men in the Cabinet and to restore the mandatory long-form census, for example, were fulfilled by executive decrees in the first weeks of the mandate. Other pledges in the same category, such as the promise to restore funding for CBC/Radio Canada and to introduce the new Canada Child Benefit, were fulfilled when the March 2016 budget was adopted. Another 30 percent of campaign promises have been “kept in part” or are “in the works.” The promise to work with the provinces to establish national emission reduction targets is included in that category, as are many other promises that still require agreement from the provinces before they can be considered fully kept.

Promises in the “kept in part” category also include government decisions such as the pledge to reinstate door-to-door mail delivery, which seems likely to end in a compromise following public consultations. Most of the remaining promises (44 percent) have not led to an official action to fulfill them and are classified as “not yet rated.” The promise to remove marijuana possession from the Criminal Code falls into that category along with some other marijuana-related promises on hold while we await the report of the federal-provincial task force, whose creation constitutes a kept promise. Fewer than 2 percent of Trudeau’s promises have been declared “broken,” the most salient among them being the promise to run modest deficits of $10 billion in the two first years which the government reneged upon when it announced a $30-billion deficit in the March 2016 budget.

Justin Trudeau is at the top of the list

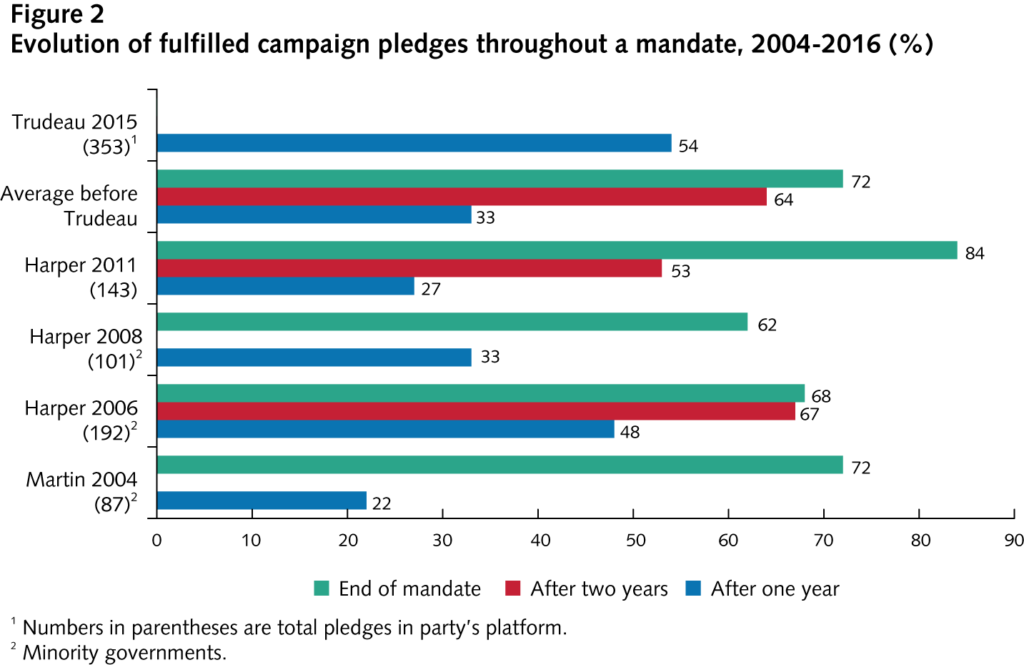

Beyond the simple description of the level of fulfillment of specific campaign promises, we take advantage of the pledge fulfillment data collected by the Polimeter over the years to compare Justin Trudeau’s promise-keeping performance with that of the governments that preceded it (Figure 2). To make valid comparisons, the diagram compares the promises that were fulfilled entirely or in part by each government after one year, after two years, and at the end of each mandate. The numbers in parentheses are the total pledges in a party’s platform. The governments indexed with three stars are minority governments. The data show that the number of promises kept entirely or in part after one year by the Trudeau government (54%) clearly outweighs its predecessors’ average after one year (33%). This requires an explanation.

Being a majority government does not affect pledge fulfillment in the first year

The Trudeau government enjoys a majority in Parliament, unlike three of the four governments that preceded it. This might explain why it has fulfilled more promises after one year: perhaps the lack of parliamentary support from opposition parties prevents minority governments from passing measures that would fulfill their promises. That theory does not stand up to scrutiny, however. A detailed study of the fulfillment of campaign promises in past Canadian governments shows that on many issues, opposition parties made election promises that were identical or very similar to those by the governing party. Minority governments of the past were able to fulfill their promises on those issues because cooperation or compromise with one or more opposition parties, not division, tended to emerge on these issues.

The data in the second diagram refute the notion that minority governments are prevented from fulfilling their promises. After one year in power, the three minority governments that preceded the Trudeau government fulfilled more promises on average (34 percent) than the Harper majority government elected in 2011 (27 percent). After two years, the average score for minority governments (67 percent) still exceeded the score of the majority government of Stephen Harper (53 percent). It was not until the end of its mandate that Harper’s majority government managed to exceed the average score of minority governments, simply because it lasted longer than they did. We have no way of knowing whether the Liberal government of Justin Trudeau would have kept as many promises after one year if it had been a minority government. However, the evidence from past governments strongly suggests that its majority status has not been a factor in its first year, although it might become one later in its mandate because it will allow the Trudeau government to reach its natural four-year term.

Being a new party in power made a difference in the first year

The rise to power of Justin Trudeau’s Liberals corresponded to an ideological shift from a Conservative right-of-centre ideology to a Liberal left-of-centre ideology. Could this ideological shift explain the unusually high promise-keeping score of Justin Trudeau after one year? The theory here is that, unlike re-elected governments, newly elected “activist” governments make many ideologically inspired promises that they are eager to fulfill. Add to this all the promises to reverse the policies of the outgoing government, in contrast to re-elected governments which tend to pursue their ongoing policy agendas. As a result, a newly elected government will not only have made more promises to change policy directions in their election platform than re-elected governments, but will also have more desire and opportunities to fulfill them.

The data support this theory: newly elected governments make more promises and fulfill a higher percentage of them in the first year than re-elected governments. This is of course the case of Justin Trudeau’s government with 54 percent of 353 promises fulfilled in the first year. It was also the case of Stephen Harper’s first government, with 48 percent of 192 promises fulfilled in the first year. However, the effect disappeared later in the Harper mandate. Stephen Harper fulfilled fewer promises (68 percent) at the end of his first mandate than the average for all governments at the same stage (72 percent).

The ideological change that corresponded to the arrival of Justin Trudeau in power was a factor in the unusually high number of promises made after one year. However, judging by the fate of the promises of past governments, this factor will probably run its course after the first year of the Trudeau government.

Running a big budget deficit helped

Fiscal liberalism was also a factor that helped the Trudeau government keep some promises in the first year. By creating a deficit of $30 billion in its first budget in May 2016, Finance Minister Bill Morneau broke the Liberal commitment to create a modest deficit of $10 billion. However, in doing so, he gave the government some leeway to quickly fulfill several election promises aimed in particular at strengthening the social safety net, including the pledge to increase the Guaranteed Income Supplement for low-income seniors and the pledge to reduce the waiting period for Employment Insurance benefits.

The contrast with the strategy of the Quebec Liberal government of Philippe Couillard elected in 2014 is revealing in this respect. True to his promise to balance the budget as quickly as possible, Philippe Couillard implemented an extensive fiscal austerity plan that prevented his government from fulfilling many election promises in his first year. After one year in power, Philippe Couillard’s government had achieved 41 percent of its promises, 13 percentage points less than Justin Trudeau at the same stage.

If the deficit strategy of the Trudeau government facilitated the fulfillment of some promises in the first year, it could have the opposite effect in the longer term. By creating a large deficit early in his mandate, Justin Trudeau took a calculated risk: an economic recession in the next year or two could threaten the sustainability of funding several of his promises. The second Harper government, which came to power on the eve of the Great Recession of 2008-2009, provides evidence of the powerful pressure that economic downturns can exercise on the capacity of governments to fulfill their election promises. Anxious to preserve its fiscal position, the Harper government cut the budgets of several ministries, and these cuts prevented the fulfillment of several election promises. This explains in part why the second Harper government fulfilled only 62 percent of its promises, the lowest score since 2004.

The fulfillment of election promises will slow down in the second year

Will Trudeau manage to fulfill promises at the same pace in his second year? This is unlikely given the fact that sooner or later, diminishing returns will take hold of promise-keeping by the Liberal government. In addition, many promises not yet rated touch on complex issues whose implementation is likely to face serious political and administrative difficulties in the months ahead. Consider the promises to negotiate a new Health Accord with the provinces, to enact electoral reform, or to remove marijuana possession from the Criminal Code. The Liberal government is working on these promises. It has already set up a special parliamentary committee on electoral reform and a marijuana task force, as promised in its campaign platform. However, keeping these transactional pledges is only a first step toward the ultimate outcome. The road ahead is fraught with so many obstacles that we cannot discount the possibility that some of these promises will be declared broken in the end.

The Liberal government still has two tricks up its sleeve to try to fulfill as many promises as possible.

Like Harper before him, Trudeau has placed the fulfillment of his campaign promises at centre stage of his leadership as Prime Minister. Like Harper, he made a point of reminding his cabinet ministers of the party’s campaign promises in his mandate letters to them. Unlike Harper, however, he had these mandate letters published in the media. And he has appointed Matthew Mendelsohn as the head of a new “results and delivery” unit within the Privy Council Office to ensure that government ministers are working effectively to fulfill the party’s election pledges.

Second, Justin Trudeau has accumulated much political capital. He remains highly popular with the public, he won the respect of foreign political leaders, and his style of governance is appreciated by federal officials. Time will tell if he will exploit this political capital to consolidate his leadership and perpetuate his ability to fulfill his campaign promises in the troubled political times that lie ahead.

The Polimeter is funded by a grant from the Fonds de recherche québécois société et culture. You can follow us on Facebook https://www.facebook.com/TrudeauPolimeter/

Photo: Justin Tang / The Canadian Press

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.