Sign up for A Stronger Canada for The Trump Era. A temporary newsletter with the latest Canada-U.S. analyses from Policy Options.

(Version française disponible ici)

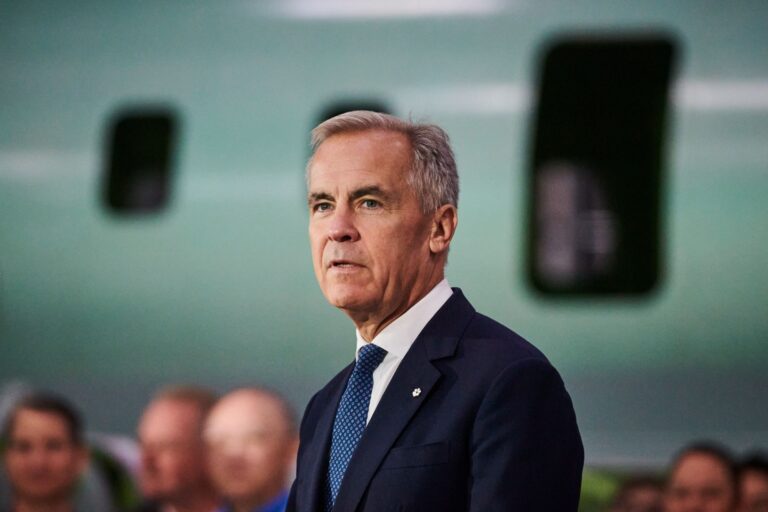

OTTAWA—Jocelyne Bourgon, a key player in Canada’s historic 1990s fiscal turnaround, says reforming the public service is critical to the success of Prime Minister Mark Carney’s economic agenda — but this time, it doesn’t have to mean deep cuts and mass layoffs.

Bourgon, the former clerk of the Privy Council Office during the Chretien government’s massive downsizing, said Carney’s ambitious economic plans must ‘converge’ with a fundamental rethinking of how government works. That means not just new policy, but a public service equipped to deliver it.

“The government agenda and the public service reform agenda must converge and reinforce each other,” she said at this year’s Manion Lecture. “A technologically and digitally advanced public sector is necessary to support a modern technologically and digitally advanced economy and society.”

Bourgon has written extensively on program review and advised governments around the world on modernization — in areas where Canada’s public service now faces major challenges. Her lecture comes amid questions over whether the public service can even deliver on Carney’s agenda. He has pledged to cap its size, cut internal spending, and launch a program review – but details are thin.

In the 1990s, Canada faced a full-blown fiscal crisis — the country was dubbed “an honorary member of the Third World” by the Wall Street Journal — and launched a sweeping program review that balanced the books by slashing programs and cutting 50,000 public service jobs. Bourgon was at the heart of that overhaul, helping the country regain what she calls its “fiscal sovereignty.”

Sign up to The Functionary, Kathryn May’s newletter covering the public service

Now, she says, the country needs a similarly ambitious overhaul to regain its economic sovereignty. But this time is different. What worked in the 1990s – or even the 1980s, when the public service endured 22 rounds of across-the-board cuts – won’t work today. But there are lessons to be learned.

This time, government must grow and shrink simultaneously. Some departments – such as defence, border management, Arctic security, and trade – will expand, potentially “easing the transition” for workers in areas facing reductions or closure, she said.

That’s more about realigning government – reallocating people and money – than shrinking it.

“The solution you are looking for is not a death by 1,000 cuts like in the 1980s, or a drastic contraction on the scale of what was done in the mid-1990s. Your challenge is to do more in some areas, less in others, reallocate resources, and reinvest to modernize government and society,” she told a mostly public-service audience.

Reallocating means learning how to adapt to change and will help “break from the boom-and-bust approach that has characterized budgeting in Canada,” she said.

Today, technology – including AI and digital tools – has the potential to modernize government in ways and at a speed not possible decades ago. Also, in the 1990s, Canada was embracing free trade, globalization, and deepening ties with the U.S. – a world order now being upended by Trump.

But budget cuts don’t improve service, productivity, or modernize government and often push government into making wrong decisions like cutting training, travel and conferences, says Bourgon.

Bourgon argues the 1990s program review, a rethinking of the role of government, worked because programs were privatized, transferred to provinces, or scrapped. But the fact that such a sweeping review was needed at all, she says, reveals the consequences of failing to regularly reallocate people and resources with shifting priorities. Instead, governments wait for a crisis – disrupting thousands of jobs and dominating the Chrétien government’s early years.

Bourgon’s biggest concern is the decline in service delivery. She’s calling for a “Service to Canadians Review” – not to decide what to cut, but what must be preserved. As she put it, “knowing what to protect brings clarity to what may be stopped.”

“Modernizing government, improving services, and reducing its footprint doesn’t start with cuts. It starts by asking what needs to be protected,” she said. “That means preserving the knowledge and public assets needed to make decisions in the public interest.”

That includes research and institutional knowledge, like meteorology, oceanography, technology, and early-warning systems – foundational tools for tackling climate change, instability, and whatever crisis comes next.

The public service has expanded rapidly in the last decade, with executive ranks more than doubling. Yet Canadians wonder what they’re getting in return. Wait times grow, backlogs persist, systems fail, and corruption cases emerge. Since 2015, Canada has dropped from a top-10 ranking in e-government to 47th, just behind Mongolia. Canada is also the only G7 country without a single login system for government services – which would make services easier to use and cheaper to deliver.

Of the $500-billion federal budget, most goes to transfers and benefits for people and provinces. What’s left – about $225 billion – covers everything else. The $123-billion operating budget is where cuts could come. The rest funds the programs departments run, the slice Bourgon would put under the microscope to assess whether resources still match government priorities. (Departments have two jobs – deliver frontline services and support government decisions with research and advice.)

Before turning to departments and programs, Bourgon urged public servants to first explore a “better way” — smart, strategic options that could “make room,” generating savings, reduce complexity, and rebuild a financial cushion.

“A whole host of avenues are open to you,” she said. “Your search for a better way begins by expanding the space of possibilities to make room to replenish government’s war chest and to build contingency reserves, to simplify in every way you can, and to explore avenues that were not explored before.”

Among areas to start with:

Previous promises: Governments should take a hard look at pre-election and election commitments. If they no longer fit the fiscal or policy needs, restructure, postpone – or drop them. Finding cheaper ways to deliver them should also be on the table, too.

Review temporary funding: Governments have long relied on “temporary funding” for short-term initiatives, which can be up to 30 per cent of some departments’ budgets. This distorts the true deficit picture, encourages governments to focus on “announceables,” and leaves others to manage expiring funds. Review them to ensure these initiatives align with government priorities, such as reducing dependency on the U.S., or to phase them out altogether.

Tax Expenditures: Canada’s tax system hasn’t been reassessed since the 1960s, and most tax credits and exemptions haven’t been reviewed since the ’80s. Bourgon says revisiting them could yield more savings than any program review could.

Simplify, simplify, simplify: A key step is to simplify – everything. From regulations, legislation, to forms to internal processes, simplification is its own type of reform, and one that could make government more effective and less costly.

Agencies and Structures: When Bourgon was clerk, there were 109 departments, agencies, and Crown corporations. Today, there may be 250 – or more. That growth has brought over 2,000 senior executives, each with internal supports. Has it improved results? She suggests full portfolio-level reviews to cut, consolidate, or integrate agencies.

Central agencies: Since 2000, the budgets of the Privy Council Office, Treasury Board, and Finance have soared — up 250 per cent, 540 per cent and 220 per cent respectively. Bourgon says it’s time to review them. When central agencies get too operational, she warns, they lose the big picture. Bogged down in transactions, they stop thinking strategically – and when excellence slips, the public service falls behind its global peers.

Start at the top: Look at political staff. Their ranks have swelled to 765, up 60 per cent since 2011 and six times more than the U.K., a country with nearly double our population. Shrink the number and refocus their roles on building political alliances, maintaining party unity, and managing Parliament. The savings might be small, but the message is powerful.

And, she notes, a smaller cabinet also performs better – and costs less.