When it comes to the cost of putting a roof over your head, those who call Canada home today find themselves adrift in dauntingly uncharted waters.

An average cost of a Canadian home more than doubled in value since 2011. Royal LePage estimates that, by the end of 2024, the median price of a detached single-family house will be roughly $843,000 nationally, $1.48 million in the Greater Toronto Area, and $1.77 million in greater Vancouver. Rents in Canada have become substantially more burdensome at the same time, increasing by nearly 10 per cent from 2022 to 2023.

In short, Canada has a housing crisis.

The federal government has made attempts to alleviate the high cost of homeownership through policies like foreign-ownership bans and the elimination of the GST on purpose-built new rental construction. However, these measures are a drop in the bucket to the larger problem at hand: Canada does not have enough housing supply. Recent estimates suggest that by 2030, the Canadian housing shortage will reach 3.5 million units.

Yet there exists opposition to increasing the supply of new housing in Canada. Scotiabank’s chief economist recently argued that local opposition to housing development remains a considerable barrier to reducing home prices.

Anecdotally, the root cause of this is opposition from so-called NIMBYs. There is, to be sure, ample evidence to support this. Notable Canadians including Margaret Atwood and Galen Weston have voiced opposition to local housing developments.

Such opposition can sometimes be absurdly comical. A movement in Toronto’s East York borough mobilized to prevent the demolition of a parking lot to build affordable housing, saying that it would remove the “heart of the community.”

Who are these NIMBYs? Despite their apparent prevalence in media and behind the scenes, such movements have not been studied extensively.

Some existing research does examine how homeownership shapes NIMBY attitudes: opposition to new housing is rational insofar as existing homeowners oppose the construction of new houses because it increases supply and thus lowers their property values.

But is NIMBYism just a simple investment protection, or a deeper attitude shaped by fundamental values? In our ongoing research, we are able to determine that NIMBYs are only one piece of the puzzle.

How values affect housing policy

What do we mean by values? In our work, we focus on deeper worldviews like egalitarianism, support for free markets, nativism, and traditionalism.

For example, people with egalitarian worldviews may be more supportive of housing to reduce important inequities in society.

Meanwhile, free marketers may value rolling back government red tape and zoning regulations that make it harder to build supply.

Nativists may have concerns about who their new neighbours will be in the context of soaring levels of immigration in Canada.

Traditionalists may see new housing as a threat to traditional single-family neighbourhoods.

We fielded a survey on a representative sample of adults in Canada and asked them about their beliefs, concerns, and support for new housing in their communities and potential government policies to address the crisis.

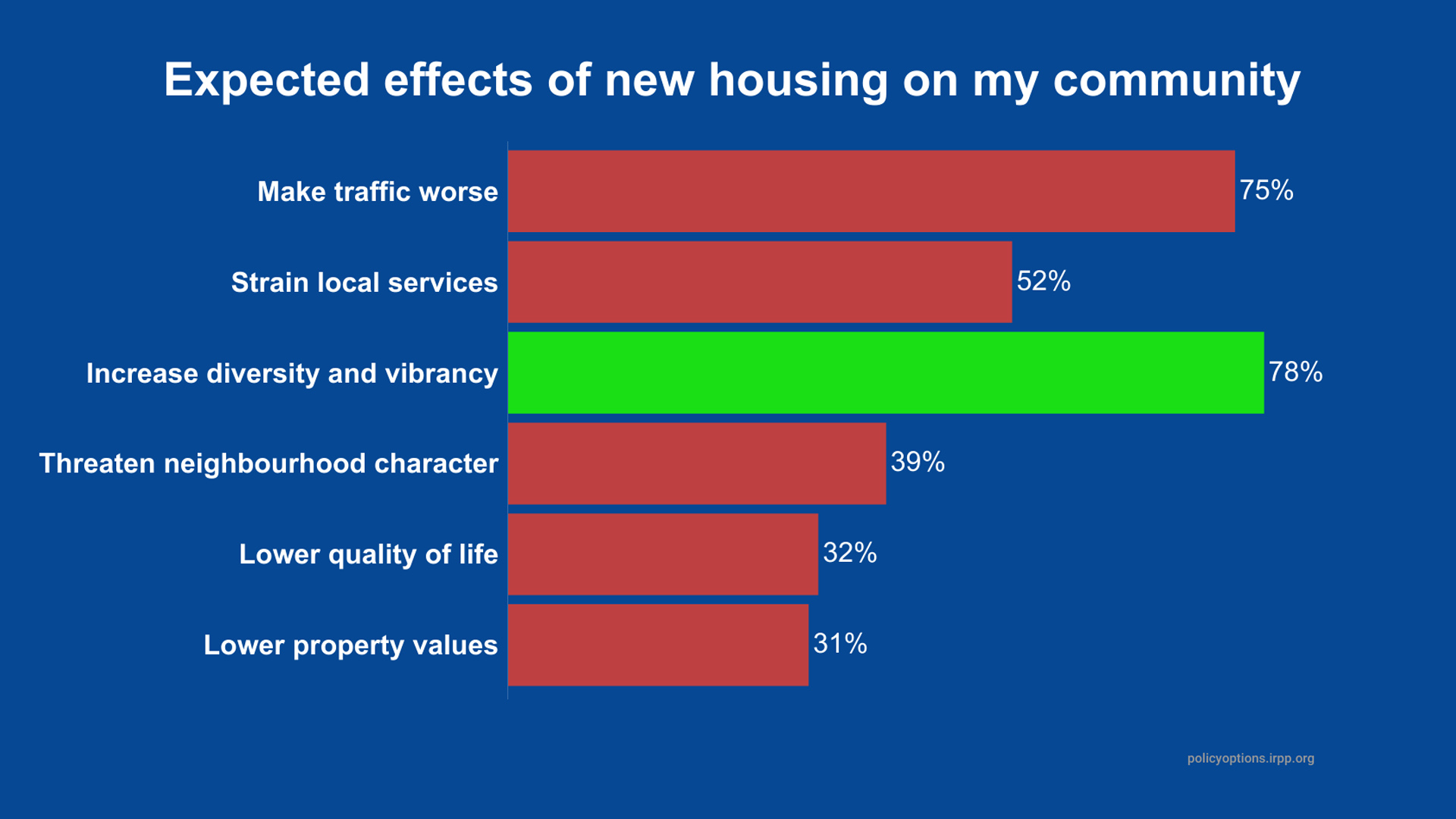

Canadians have nuanced attitudes towards new housing. On the one hand, they can envision some negative consequences—75 per cent think it will make traffic worse and a slim majority (52 per cent) think that new housing will strain government and social services.

On the other hand, 78 per cent think new housing will increase the diversity and vibrancy of their neighbourhood, while only 39 per cent see new housing as a threat to their neighbourhood character, and only 32 per cent think it will lower the quality of their life. Interestingly, only 31 per cent of homeowners believe new housing will lower their property values.

When asked about a hypothetical housing development in their neighbourhood, 74 per cent of Canadians indicate some level of support. It is lower for high-rises (60 per cent) compared to multi-family homes (75 per cent) and single-family homes (81 per cent), and for developments on their block (65 per cent). Support for developments up to 4 kilometers away goes up to 79 per cent.

Only in the case of high-rise apartments on their block are most Canadians opposed to nearby housing development (52 per cent).

Canadians are far from being in lockstep with NIMBY talking points. Sixty-six per cent support relaxing laws and regulations to permit more housing and 62 per cent even favour the repeal of single-family zoning. Canadians are supportive of measures like foreign ownership bans (74 per cent), higher taxes on vacant homes and secondary residences (72 per cent) and building more affordable housing (87 per cent).

NIMBYs vs the silent majority

Our conclusion is clear: NIMBYs are a small but vocal minority of Canadians. That said, who are they exactly?

Our research suggests NIMBYs are concentrated among some (but not all) segments of the political right. Nativists are more hostile to local housing development, likely out of a fear that such new housing will be populated by immigrants and racial minorities. Traditionalists and social conservatives are also more opposed to new housing and supportive policies, likely because they perceive densification to be a threat to their ideal community.

By contrast, housing makes bedfellows of egalitarians and free marketers. Both favour greater support for local housing development. Housing issues also blur typical left-right political coalitions: the political left is united in favour of more housing, while the right is divided between cultural and economic conservatives.

We can see this dynamic play out in housing policy at the federal and provincial levels. The B.C. NDP have flexed their jurisdictional powers to harness the power of the market to build new housing, including tabling bills to increase density near transit hubs and by changing zoning legislation to facilitate the construction of small-scale multi-unit homes.

Can building more affordable housing be compatible with local democracy?

The federal Liberals are promoting a housing accelerator fund to incentivize municipalities to reduce red tape for new housing development.

Conservatives are in a trickier position. Previous academic research has found that the political right in Canada is not nearly as ideologically cohesive as the political left, and this shows up in the housing debate, pitting nativists and traditionalists against free-marketers.

Perhaps as a result, conservative actions on housing have occurred in fits and starts. Although initially taking a lead in tackling the housing crisis, Ontario Premier Doug Ford’s strategy has been mostly bark, and little bite. Quebec Premier François Legault also expressed indifference to rising housing prices, seeing it as a sign of greater provincial prosperity.

An exception to this, at least for now, is Pierre Poilievre’s Conservative Party which has increasingly adopted a YIMBY (Yes In My Backyard) posture. This may be viewed as a political risk given that nativists and traditionalists tend to vote Conservative. Poilievre must walk a tightrope to appease NIMBYs in his voter coalition while also putting forward a housing policy that is attractive to new voters.

Opportunity to build for the future

Our work is a first step in developing a deeper understanding of what motivates housing attitudes among Canadians. Although support for new housing is high, and NIMBYism is relatively uncommon, it can still present a major roadblock to addressing the housing shortage in Canada.

Our research offers three policy prescriptions to overcome NIMBYism.

First, governments should move to reduce or eliminate local consultation over housing developments, which only serve to derail housing initiatives. We know that those who attend local consultation meetings are more likely to oppose a housing project than to support it and that the demographic makeup of attendees does not match that of their community. We cannot let a vocal, privileged minority routinely game the system to prevail over the silent majority.

Second, Canadians are much more opposed to high-rise developments than other forms of housing. Policymakers should prioritize the legalization of “missing middle” housing – the development of which has a much wider appeal in the public, while being less likely to trigger NIMBY backlash.

Finally, policymakers need to better explain the value of housing for people with diverse value commitments. Appealing to concerns about fairness and equity may be less effective in conservative constituencies than drawing attention to the tension between zoning regulation and property rights, or to the struggle young couples face to establish and raise their families when they can’t afford a home. This might also mean harnessing the power of trusted messengers for these skeptical audiences, by building a coalition of former politicians, business and non-profit leaders to signal cross-partisan consensus on the need for more housing.

NIMBYism is undoubtedly a challenge, but we have avenues at our disposal to limit their influence and to change minds. In doing so, we will be better placed to tackle one of the most pressing challenges of our time.

Methodology note: The data presented in this article are from a pre-registered online survey of 1,400 adult Canadian citizens conducted between May 5-16, 2023, using the sample provider Abacus. A sample of this size drawn from the population produces results accurate within plus or minus 2.6 percentage points 19 times out of 20. Funding for this study was provided by the University of Toronto.

This article is part of a series called How does Canada fix the housing crisis?