(Version française disponible ici)

How is the average Canadian to know what their elected member of Parliament (MP) is up to in Ottawa?

Canada is a representative democracy – that is, one in which citizens elect representatives to make decisions on their behalf. Every four years or so, we strike a deal with our would-be representatives: tell us what you want to do, we approve or disapprove, and then we’ll re-evaluate how you did when the next election rolls around.

For a country the size and complexity of Canada, this system makes a lot of sense. The average person does not have time to weigh the nuances of every piece of legislation or every funding decision that needs to be made on any given day. So, we outsource most of that decision-making to elected officials who we trust to have our best interests at heart.

One of the things Canadians ask for in return for the power that we bestow upon our elected officials is that they keep us in the loop about what they’re doing on our behalf. Indeed, a basic tenet of democracy is that the people’s elected representatives need to communicate with their constituents. But connecting with everyone in an electoral district is a chronic challenge for members of Parliament, especially as community news outlets close, people’s media consumption splinters and party leaders’ offices co-ordinate messaging. What is the best way for MPs to get information about public affairs to everyone they represent?

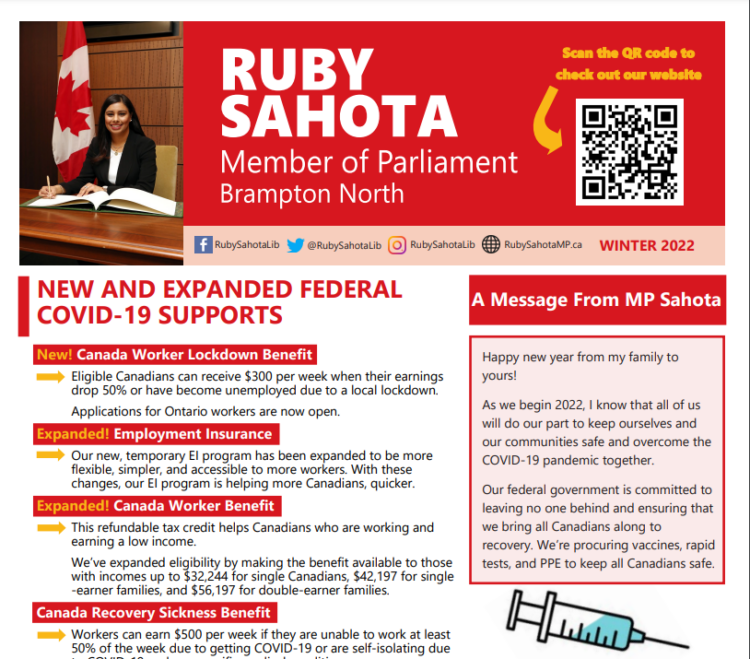

One solution to this problem is commonly referred to as the “householder” – newsletters paid for by the House of Commons that Canada Post distributes at no charge to all households in each MP’s electoral district. You may have seen one in your mailbox, though maybe all you saw was your MPs’ smiling face as you tossed it into a recycling bin.

MPs and their staff devote a considerable amount of time to assembling these tabloid-size brochures because householders are arguably the best way to reach all constituents, including those who do not follow MPs on social media or subscribe to their email newsletters.

Typically, a masthead across the top features a photograph of the MP and the MP’s name, under which is a personal message. Roughly four pages in total, the documents are peppered with photographs of an attentive MP mingling with constituents and/or talking on the floor of the legislature. There are textboxes updating constituents about government initiatives and House business, and often a form for readers to share opinions, which can be mailed to the MP’s office, postage-free.

Householders keep MPs in tune with the people they were elected to represent; for example, in House of Commons debates, MPs have been known to reference the feedback they collect via mail-back surveys. They also inform electioneering and fundraising efforts, even if those are not explicitly allowed. That’s because householders are subject to the same restrictions as everything else the House of Commons pays for – for example, they may not be used to solicit party memberships or donations and cannot be used for disseminating campaign material. Otherwise, their content is largely left up to each individual MP, and it is difficult for the public to enforce compliance without a central repository. We’ll get to that in a moment.

Some MPs’ offices are proactive by posting their householders online for anyone to access, or inviting constructive criticism. Sean Fraser, the Liberal MP for Central Nova, is one such MP. His website has a householders section that explains that every household and business in his electoral district will periodically receive a newsletter prepared by his office with information about “key government updates, news, what’s happening in Ottawa, funding announcements and photos from throughout the riding.” There are PDFs of his householders going back several years. Furthermore, Fraser’s website says that he is open to feedback about the content and that he welcomes suggestions.

It is the collection of large and small acts of transparency, like MPs posting their householders online, that helps rank Canada as one of the best democracies in the world. Canadians might therefore expect that making householders readily available to anyone who requests one is normal.

Not so.

The considerable challenges we experienced trying to collect these taxpayer-funded public documents reveal some disturbing truths about the partisan paranoia running amok across Parliament Hill.

Beginning in 2021, we managed to collect householders from 126 MPs in the 43rd Parliament. Some documents were available online. For the rest, we emailed, phoned and mailed the MPs’ Parliament Hill and constituency offices. Then we emailed and phoned some more. Initially, our efforts were interrupted by the snap August election call. In the lead-up to the dissolution of Parliament, there were hesitancies among MPs and staff who presumably worried about the content of householders being weaponized against them by other candidates and parties. Perhaps some worried that they would be criticized for admitting that they did not issue a householder during the throes of the pandemic. We carried on after the election by contacting the many MPs who were returned to office.

Lots of MPs and their staff were terrific, and enthusiastically supplied the documents electronically or by mail. Yet despite the fact that householders are designed for public consumption, are sent to tens of thousands of households, and are paid for with public funds, we were only able to collect them from 37 per cent of all members of Parliament.

Why did 63 per cent of MPs refuse to make their householders available? In the early stages of the pandemic in 2020, the House of Commons paused the practice, and so some MPs pivoted to email newsletters, various forms of social media and video chats. When the service resumed, staff in MPs’ offices were consumed with constituency casework, and they lacked the usual suite of photographs of the MP mingling with constituents or addressing the House. Some staff told us they were working remotely and did not have access to digital copies stored on a network or paper copies archived in the office. One MP told us that they are bombarded with requests, and staff can only do so much. Many completely ignored our repeated pleas.

But the main reason that MPs are so secretive about their householders seems to be fear of getting in trouble.

Some MPs and their staff asked us to provide more information about how the householders would be used. Others cryptically said they were unable to offer examples, including a minister’s office that ignored our requests to explain why. Some flat out said they would not provide the newsletters. One MP said that he does not participate in any academic research.

Some staff specified that householders are intended exclusively for constituents. As one staffer put it, “we did send out householders during the pandemic, however it is an office policy that we do not give out documents to non-constituents that prevents me from sharing.” One staffer told us to get our local MP to place the request for us – and when our local MP’s office did so, the request was ignored. A few staff promised that the householders would soon be posted on the MP’s website, but never were. One MP even admonished a student assistant, saying that he would not provide his householder because staff had found information about her attending another political party’s event.

Knowing what MPs are saying to constituents matters, as does whether they emphasize community issues or happenings in Ottawa, and what information they choose to highlight. There are 338 MPs, and studying so many of them in such a large country is challenging. We can hardly job shadow all MPs, and there is no historical record of these documents. Further, having access to all householders would enable us to identify to what extent MPs are repeating party messages, or whether they are contradicting each other – which might explain their anxiety in a country riddled with strict party discipline.

There is an easy fix for empowering MPs: be guided by the government of Canada’s “open by default” policy. The Board of Internal Economy, chaired by the Speaker, should direct the House of Commons to maintain a permanent online archive of householders, or to deposit them with the Library of Parliament. Party spokespersons refused comment when The Canadian Press recently asked about the secrecy surrounding householders. As mentioned, Canada’s democracy is among the strongest in the world. However, democracy must evolve; it is a constant work in progress. We should be deeply concerned whenever MPs from all political parties do not want to talk about House business.

It is high time for more accountability and transparency, and for MPs and their staff to stop controlling whether Canadians outside of their electoral district can obtain a copy of their householders. Millions of dollars of public funds are spent on householders each year. The Board of Internal Economy should amend the members by-law to stipulate that an electronic copy of an MP’s householder must be provided to an online House of Commons repository in order to be eligible for funding. We would like to see a requirement that digital copies of householders must be routinely submitted to the Library of Parliament for permanent online archiving. MPs work for the public – their publicly funded communications should be open, transparent and, above all, accessible.

This article is part of the Making a Better Parliament special feature series.