Commentators who conjure up images of the “end” definitely get our attention. Most prominent in this vein are Francis Fukuyama’s The End of History and Jeremy Rifkin’s The End of Work. While these forecasts were wrong, a close look at public opinion reveals that Canadians today are harbouring an increasingly gloomy notion that progress as we came to understand it in the 20th century has ground to a halt.

Indeed, there’s mounting evidence that the era of shared prosperity and middle class growth has, in a word, ended. Yet digging deeper into Canadians’ work experiences and expectations, we find positive indications that we can can kick-start progress by making jobs and workplaces more knowledge intensive, smart and agile. This approach, the details of which are provided by the feedback Canadians have given us about the limits and possibilities in their present jobs, is a blueprint for a more innovative and prosperous economy.

Jobs but no progress

The jobless recovery after the recession of early 1990s and the onslaught of information technology provided fertile ground for Jeremy Rifkin’s dystopic “end of work” thesis. The idea that jobs would rapidly be displaced by information technology seemed to be becoming a reality.

Today’s advancing digital technologies, particularly robotics and artificial intelligence, also have sparked predictions of massive job losses. A recent Growth Council report predicts that 40 percent of jobs in Canada could be replaced by technology in the next five years. The Munk School’s David Ticoll reflected on whether some of those estimates might be too low, taking into account jobs that are simply made obsolete by automation.

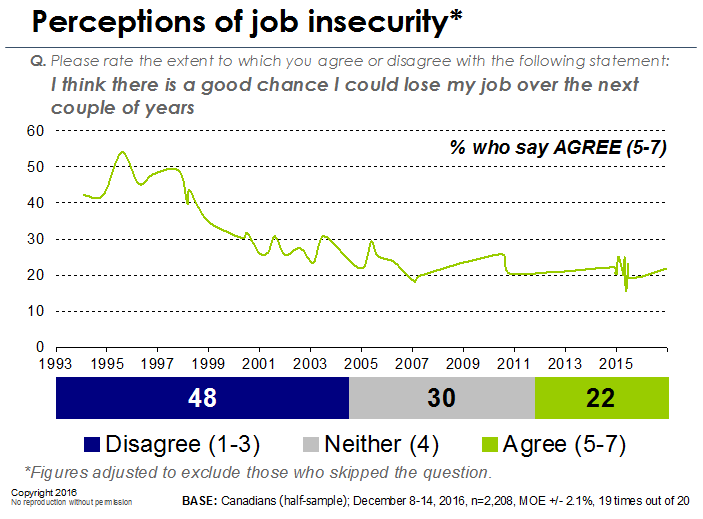

But other labour market trends paint a different picture, one in which jobs are available and unemployment low. A signal indicator in this regard is EKOS’s tracking of job insecurity. Compared to today, concerns over job security were much higher 20 years ago, when a majority of workers were worried about losing their job (see Figure 1).

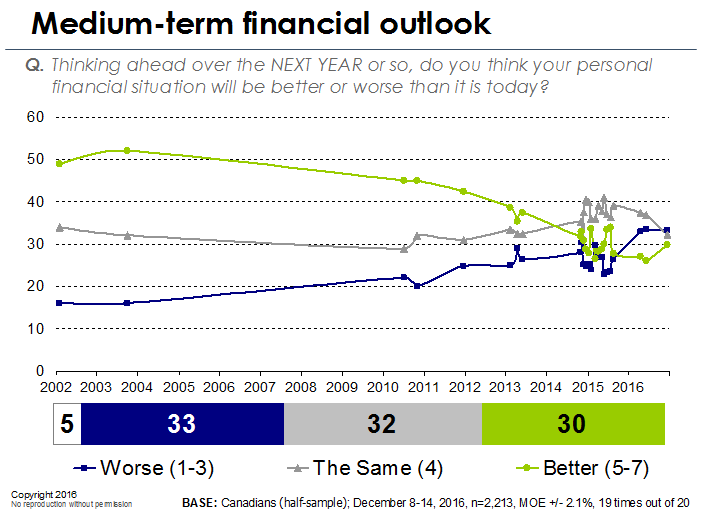

While Canadian workers may feel more confident about their job security today, this is overshadowed by an increasingly pessimistic outlook since the early 2000s about their personal financial outlook (Figure 2). Basically, many Canadians feel they are falling backward into the future. What it all adds up to, certainly in the public mind, is indeed the end of progress as Canadians have known it.

The fading middle class dream

What’s behind this now pervasive sense among Canadians that progress seems to be stalled?

Our book Redesigning Work provides key insights into how the labour market is both reflecting and driving this disturbing downturn in economic outlook (see our Policy Options article about the book here). Not long ago, most Canadians embraced the idea that when they were adults their kids would enjoy better living standards than they do. Fading fast is the middle class dream that education, skills and hard work would produce a life better than one’s parents – progress that was expected to continue from generation to generation.

Now the public is deeply concerned about declining living standards, a growing gap between haves and have nots and reduced prospects for the next generation. For example, only nine percent of Canadians think their children will do better than them, according to a recent survey EKOS conducted. These public opinion trends predate the Great Recession of 2008-09. The recession added momentum to the trends by disrupting economic life in ways that further unsettled many Canadians.

More accentuated versions of the same concerns about what can be called “the end of progress” unleashed the anger, fear and a populist backlash that has resulted in the Donald Trump presidency and Brexit. Canada has escaped these more extreme public reactions, at least so far.

The changing world of work

Some popular images of the new world of work miss the mark. The notion that there are no permanent jobs and that workers will constantly migrate from job to job doesn’t line up with our tracking data. Job tenure is the same today as it was 15 years ago.

Still, one dramatic change has been the proliferation of low-quality jobs. Nonstandard, part-time jobs have burgeoned, intensification of work has pushed up stress levels, union membership has dwindled, and opportunities for workers to apply their knowledge have not kept up with the increasingly well-educated workforce. And for most workers, real wages have remained stubbornly stagnant, while there are visible signs that an increasingly privileged group of professionals, senior managers and business owners have enjoyed windfall gains.

In Redesigning Work we trace how workers’ values, morale and quality of work-life have declined since the early 2000s. Of great importance, the level of skill confidence has declined, as has the incidence of job training in the workplace. The mid-20th century incentive system that underpinned the era of shared prosperity has broken down. In response, many workers – especially younger ones – are coping by adopting a “hunkering down” approach to work. The upshot is that investment in skills is being eschewed by workers because they feel it won’t be rewarded.

The ideal job

Redesigning Work moves beyond this rather dark prognosis for jobs and the economy. We asked workers a series of probing questions about what they value in work, what motivates them to go to work and what could increase this motivation, and where there are opportunities to use their skills. This enabled us to fashion a clear picture of the kinds of jobs and workplaces that not only have the potential to kick-start prosperity, but also will contribute to an overall improvement in the quality of Canadians’ work-life.

This grassroots view of what truly motivates workers is a recipe for creating great jobs. For the workers we have surveyed for the book, the following four areas of work matter:

- Relationships: positive and productive relationships with co-workers, supervisors, seniors management, and customers or clients

- Tasks: challenging and interesting and a source of pride and accomplishment

- Environment: workplaces that are safe, healthy, flexible and enable work-life balance

- Economics: decent pay, benefits, security, and advancement opportunities

When we speak about “smarter” work, it includes these desirable job and workplace attributes.

It also entails fostering a workplace where the existing skills and knowledge of employees are constantly being applied, but also being upgraded on an ongoing basis. Firms that embrace smarter work aim to have the highest possible level of human capital, either through acquiring workers with advanced higher education or through workplace training to enhance and update skills.

In search of smarter work

How can we bring about these changes in work? As a start, it’s worth revisiting the lively mid-1990s debate about how to move the economy forward. Former federal cabinet minister Lloyd Axworthy championed a model of active labour markets and stressing life-long learning. Broadly, there was a strong public consensus that knowledge and skills should determine the success of individuals, firms and the economy.

An alternative model, which reflected mounting fears of a fiscal crisis, advocated lower taxes, deregulation, cuts to social programs, and an aggressive deficit elimination schedule. It was this model, at the time championed by prime minister Paul Martin, that prevailed. The active labour market models – with their emphasis on investment in skills, relocation assistance and self-employment opportunities – were largely abandoned in pursuit of fiscal rectitude.

In today’s environment of stalled economic progress, it is timely to revisit and update our thinking about active labour markets. Within the panoply of strategies included in active labour markets, nothing resonates more strongly – certainly for the public – than the idea of stronger skills and knowledge and a smarter, more agile workplace.

Today it makes sense to equip workers with flexible skills that can be constantly refreshed to meet challenges of exponential change. Our research in this area has shown that this works best in the workplace rather than in institutional settings. Yet this past consensus on the need for a smarter, more agile labour force is in contrast to some key public opinions.

For example, EKOS polling 20 years ago showed the public strongly supported increased federal investment in post-secondary education (64%). This support has dropped nearly in half since then (37%), reflecting a growing sense that a university education is not the good investment it used to be. Even if predictions about robots, the “Internet of things” and a wider application of artificial intelligence are only partly correct, many future jobs will require more, not less, knowledge and creativity.

Smarter jobs and workplaces – or, you could say, a smarter labour market – is the clear public preference. This is what will generate public buy-in of an innovation agenda. It is at the micro level of the economy, in peoples’ jobs and workplaces, that an innovation agenda can take root and become part of the daily routine of workers. In broad terms, this idea of smarter work should be at the core of a blueprint for renewing shared prosperity. And as our research shows, although there is public pessimism about the end of progress, there is equally compelling evidence that Canadian workers are prepared to embrace the idea of smarter work.

This article is part of the The Changing Nature of Work special feature.

Photo: Shutterstock.com

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.