(Version française disponible ici)

Central bank governors are concerned about the effect of wage increases on inflation. Carolyn Rogers, senior deputy governor of the Bank of Canada, said it would be difficult to bring inflation down to 2 per cent if wage growth remains stronger than in other G7 countries. The bank’s governor, Tiff Macklem, has called on companies to give below-inflation increases. In the U.S., Jerome Powell, chairman of the Federal Reserve Board, blames high wage growth as the main obstacle to fighting inflation.

Yet, in recent years, wages have grown more slowly than prices, and workers’ purchasing power has declined. Between April 2021 and April 2023, consumer prices rose at an annual rate of 5.6 per cent, while wages grew by only 4.2 per cent, according to Statistics Canada (see figure 1). Does the fight against inflation necessarily involve further reductions in workers’ purchasing power? It’s doubtful.

Central banks are worried about a possible wage-price-wage spiral, which can be described as follows: strong economic activity increases demand for workers, which generates wage increases; these wage increases push up production costs, forcing companies to raise their prices; these price increases encourage workers to demand additional wage increases to maintain their purchasing power, pushing companies to raise their prices further. And the spiral continues until the economy collapses under very high inflation and interest rates.

What the bank’s models assume

This fear is based on questionable premises. Central bank economic models assume that companies will only charge higher prices if their production costs (actual or anticipated) rise. If companies raise their prices more quickly, competition will quickly force them to adjust their prices in line with rising costs, or eliminate them altogether. In such models, only a real or anticipated drop in production costs, which are dominated by labour costs, can bring prices down persistently. Any reduction in inflation must therefore involve a reduction in wage growth.

This is not a bad representation when the economy is competitive and profit margins are “extremely low,” much as the CEOs of the big grocery chains have argued before federal MPs. But we know that competition is pretty weak when there are only three major grocery chains in the country…

There’s still a lot of debate on this subject, but most of the research suggests that companies adjust their prices according to the demand for their products. In other words, companies will charge as high a price as people are willing to pay. Only then will they adjust wages. A vast body of empirical literature (including studies by the Bank of Canada) has long demonstrated that wages are determined by changes in prices, and not vice versa.

This means that strong demand (relative to supply) is often associated with higher profit margins. In fact, a recent study by the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City suggests that more than half of the inflation observed in 2021 came from higher profit margins.

Modernizing central bank governance

Experience since the 2008-2009 recession has shown that central bankers have tended to overreact to wage pressures, unduly penalizing workers. As a result, several countries have recently added full employment targets to their central bank mandates, and modified their governance to ensure that people from different backgrounds are involved in monetary policy decisions. The recent agreement between the federal government and the Bank of Canada on the monetary policy framework places greater emphasis on full employment, but no significant changes have been made to the Bank’s governance or mandate.

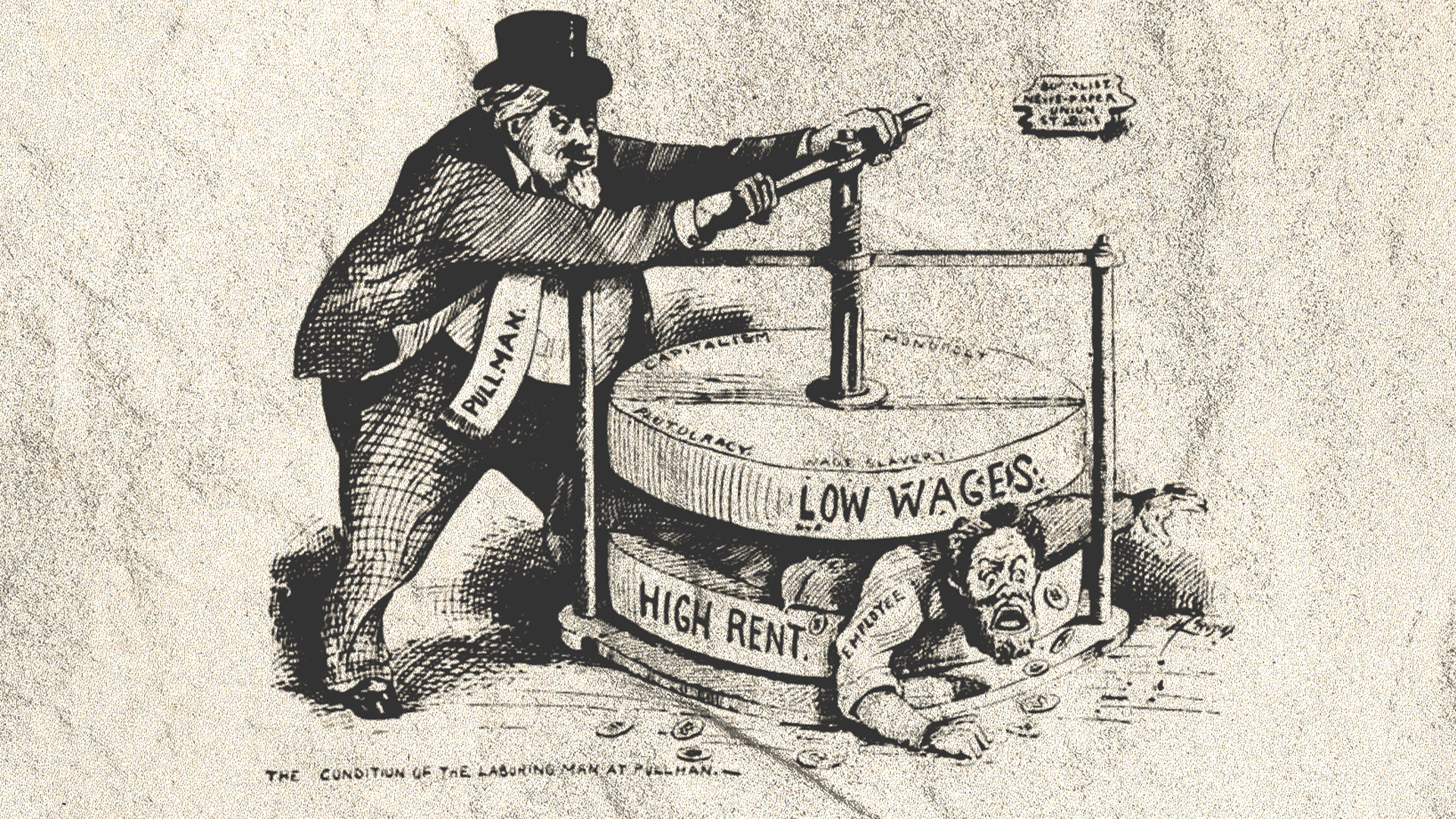

As populism rises, look at what has fallen: Wages

The economic case against low-wage temporary foreign workers

The Canadian system, in which monetary policy decisions are concentrated in the hands of the bank governor, is quite unique among advanced countries. In New Zealand, for example, and in many other countries, monetary policy decisions are made by a committee, half of whose members come from outside the central bank, including at least one union representative.

Central bankers are right to want to slow the economy to stabilize inflation. But they should avoid focusing too much on wages in their decision-making. The only way for workers to regain the purchasing power they have lost is to eventually obtain wage increases that exceed price growth. A pre-emptive or excessive rise in interest rates that hinders this catch-up could have a negative impact on workers.