In mid-January 2010, Canada sent a delegation of approximately 100 people to Brussels to take part in the second round of negotiations on the Canada-European Union (EU) Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA). Later in April, it was Ottawa’s turn to host the third negotiation round. If it is signed, CETA would be the second most important bilateral trade agreement ever negotiated by Canada, after free trade with the United States. Yet, unlike the free trade agreements with our southern neighbour, CETA has generated little public discussion and debate. Maybe everyone is waiting for the negotiations to conclude before taking positions on the agreement. Or maybe no one gets excited about Europe anymore. In any case, a wait-and-see or who-cares attitude would be unfortunate, given the potential economic and political ramifications of this deal.

Before discussing CETA’s implications for Canada, it is useful to understand how we got here in the first place. It all began in the fall of 2006 when the former EU ambassador to Canada, Dorian Prince, made it known privately, as well as publicly, that a window of opportunity was open to Canada if the latter was interested in a deeper economic partnership with the EU. At the same time, Germany, which was to hold the six-month rotating presidency of the EU in the first half of 2007, was sending out signals that it was interested in pushing for greater economic cooperation with the United States, and possibly Canada. With regional trade plateauing in North America and Europe, the Doha Round multilateral negotiations stalling and bilateral free trade deals with China unlikely, political and economic leaders on both sides of the Atlantic were looking for ways to improve market opportunities for business. This is how the old idea of the Trans-Atlantic Free Trade Agreement came to be revived. But it was when Quebec Premier Jean Charest made a strong pitch for a Canada-EU economic partnership at the World Economic Forum in Davos in January 2007 that the CETA ball was really set in motion.

It should be noted that we are not only talking about a traditional free trade agreement such as NAFTA, where customs duties (tariffs) on trade in goods and services are eliminated. We are also talking about a second-generation trade agreement where the emphasis is on nontariff barriers such as standards, procedures and regulations.

At their annual summit in Berlin on June 4, 2007, Canada and the EU agreed to cooperate on a joint study to assess the costs and benefits of a closer economic partnership between them. When we speak about an economic partnership agreement, it should be noted that we are not only talking about a traditional free trade agreement such as NAFTA, where customs duties (tariffs) on trade in goods and services are eliminated. We are also talking about a second-generation trade agreement where the emphasis is on nontariff barriers such as standards, procedures and regulations. These have become the main source of trade impediments, since tariffs are now quite low — especially those between rich countries — as a result of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) and the World Trade Organization (WTO). For instance, in 2007, Canadian goods faced an average tariff of 2.2 percent when they entered the EU, whereas at that time European goods were hit with an average tariff of 3.5 percent to enter the Canadian market.

The joint study was published a little more than a year later at the next Canada-EU summit, held in Quebec City on October 17, 2008. It concluded that a second-generation type of economic partnership agreement would allow Canada to increase its exports of goods and services to the EU by 8¤ .5 bil lion ($12.5 billion), while in return, the EU would be able to increase its exports to Canada by 1¤ 7 billion ($25 billion).

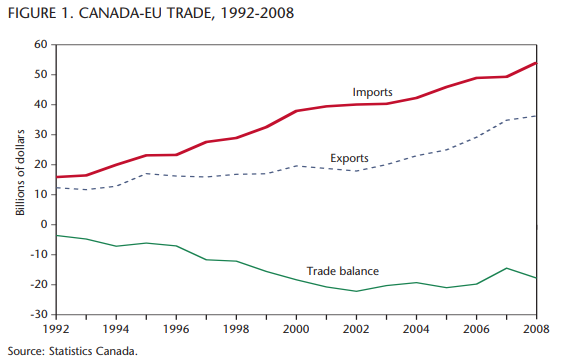

The report also suggested that GDP for the EU and Canada would increase by 11.6 billion ($17.1 billion) and 8.2 billion ($12.1 billion), respectively (see figure 1 for recent Canada-EU trade). While these amounts are not negligible in absolute terms, they account for only 0.08 percent and 0.77 percent of European and Canadian GDP, respectively. Thus, the anticipated economic gains are slight relative to the size of the European and Canadian economies. Of course, the benefits of such an agreement would not be distributed evenly among Canadian residents. According to the joint study, in Canada the metals, transport and electronic equipment sectors would see the greatest economic gains from such a deal. It can also be assumed that provinces that trade more with the EU, such as Quebec, would derive most of the economic benefits.

As well as considering the economic and trade implications of an economic partnership agreement, the joint study attempted to identify the current obstacles to trade and investment between Canada and the EU. For example, each Canadian province has different regulations, which means different requirements for recognizing professional qualifications, licences to practise and accreditations. These divergent regulations represent a barrier to labour mobility and have a negative impact on trade in services. This means that at present European engineers who want to offer their services in Canada must conform with 10 different sets of regulations. This is unconscionable. The joint study says that any agreement between Canada and the EU would need to solve issues like this, so that Europeans would be faced with a single market in Canada as they are in Europe.

Another example of a Canadian trade barrier is public procurement. At present European firms see themselves as being handicapped when provincial and territorial governments launch invitations to tender for the supply of goods and services. For example, in the case of the Montreal subway, the contract was initially awarded to Bombardier Transport, and the European company Alstom was not even invited to submit a bid. Although the WTO requires that its members treat foreign firms on an equal footing with their national companies when it comes to making deals with the government, these rules apply only to the federal government in Canada; they do not apply to the provincial, territorial or municipal governments. Canada obtained this exemption from the WTO, but the exclusion has become a focus of heavy criticism within the EU. (The recently announced deal between Canada and the US on the “Buy America” provision in fiscal stimulus legislation touches on the same issue.) The Europeans have made it clear that Canada will have to give up this exclusion if the negotiations for an economic partnership agreement are to have any chance of succeeding.

The joint study identified several other examples of this kind and tried to quantify what each would cost in terms of opportunities for trade between Canada and the EU. It also outlined several fields where Canada and the EU would benefit from more collaboration: science and technology, energy, the environment, transport, customs and education. This increased collaboration would help to improve the exchange of ideas and best practices, with the ultimate goal of getting more people and companies on both sides of the Atlantic to do deals with each other.

At the Quebec City summit, following the approval of the joint study’s conclusions, the parties agreed to undertake a scoping exercise for Canada and the EU to possibly negotiate an economic partnership agreement. The results of this scoping exercise were published in March 2009, and an agreement to start the negotiations was finalized at the Canada-EU summit held in Prague on May 6, 2009. The first round of negotiations took place in Ottawa in October 2009. The second round was held in Brussels in January 2010, with the third one returning to Ottawa three months later. So far it appears that the negotiations are progressing well, though the tough issues have yet to be tackled.

So what issues are on the negotiating table? In spite of the agreement’s second-generation nature, the elimination of tariffs on traded goods remains a key issue. According to the joint study, one-quarter to one-third of the benefits arising from a partnership agreement would come from getting rid of these duties. Both sides have made it clear that no tariff lines, even those on agricultural goods, are excluded from the negotiations a priori. It remains to be seen, however, how long it will take politically powerful agricultural lobbies on both sides of the Atlantic to force agricultural trade barriers and other distortions (for example, export subsidies and supply management mechanisms) out of the negotiations.

Many areas, such as agriculture, labour, health and the environment, are either shared or exclusive provincial jurisdictions. So the worst that could happen would be for the EU to devote time and energy to negotiating CETA only to find out that many of the provisions are not being applied or implemented by some or all of the provinces. Hence, the EU made the provinces’ active participation in the negotiations a conditio sine qua non for beginning the negotiations.

Barriers to trade in services are also high on the negotiating agenda. Again, the scoping exercise ensured that no sector would be excluded a priori. The objective is to improve market access and eliminate discrimination in favour of national providers. For example, an agreement would involve the mutual recognition of professional qualifications. This would make it easier for firms to send Canadians to Europe (or Europeans to Canada) to work with subsidiaries and/or business partners. The overall intention here is to build on the two partners’ existing WTO commitments under the aegis of the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS).

Both Canada and the EU are also keen on eliminating nontariff barriers in other areas. For instance, building on the WTO’s Agreement on Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures as well as the Canada-EU Veterinary Agreement, health-related standards and regulations that restrict trade in goods and services would have to be eliminated through harmonization or mutual recognition. In addition, there is a need for transatlantic cooperation with respect to conformity assessments. The same logic applies to customs procedures where, for example, the two sides will need to cooperate in order to ensure compliance with rules-of-origin provisions. In this case, CETA would build on the existing Canada-European Community (i.e., EU) Agreement on Customs Cooperation and Mutual Assistance in Customs Matters. Finally, in terms of nontariff barriers, the negotiations will also attempt to ease market access and put in place nondiscrimination measures in matters of investment and government procurement, as well as increase the protection and enforcement of intellectual property rights by improving on the WTO’s Trade-Related Intellectual Property Rights Agreement.

The CETA negotiations are expected to also address a dispute-settlement mechanism, competition policy, movement of persons, labour and the environment. The Canada-US Free Trade Agreement was the first bilateral free trade deal to put dispute settlement at the centre of the negotiations. Since then, most bilateral and multilateral trade-liberalizing agreements have included such mechanisms in order to render the agreements more effective. As for competition policy, there is a growing recognition that state aid and other forms of government intervention in the economy (for example, regulating monopolies) can distort the competitive nature of markets and, as a result, create barriers to trade and investment. CETA would also include measures to facilitate the temporary movement of labour for trade and investment purposes, which could mean special visas or work permits for Canadians (Europeans) working in the EU (Canada) for, let’s say, less than one year. Finally, as is the case in most bilateral trade agreements involving rich countries these days, CETA negotiators will set up cooperation mechanisms whereby Canadian and European labour and environmental laws and standards do not give one side or the other unfair trade or investment advantages. Side agreements on the environment and labour — such as those in NAFTA to assuage Americans’ fears that with less stringent labour and environmental laws and standards Mexico would “suck” their jobs south of the border — have now become a staple of bilateral trade deals.

It is clear that Canada and the EU have great ambitions for CETA. If the negotiations succeed and an agreement is reached, CETA could be a template for the rest of the world to follow when it comes to second- or next-generation preferential trade agreements (those where eliminating tariffs is not the main concern). It could even act as a prelude, or a trial run, for a wider transatlantic agreement that would include the United States, which may be the EU’s ultimate goal, and which Canada would surely not object to. But what are the conditions for success?

The crucial condition is that the provinces actively participate in the negotiations (this is why the Canadian delegation in Brussels in January 2010 consisted of about 100 people) and credibly commit to the agreement. This is because the provinces will ultimately be responsible for implementing most of the agreement’s provisions (those that deal with nontariff barriers). While customs duties (tariffs) are a federal jurisdiction, many areas, such as agriculture, labour, health and the environment, are either shared or exclusive provincial jurisdictions. So the worst that could happen would be for the EU to devote time and energy to negotiating CETA only to find out that many of the provisions are not being applied or implemented by some or all of the provinces. Hence, the EU made the provinces’ active participation in the negotiations a conditio sine qua non for beginning the negotiations. It also required that the provinces sign a political agreement that they will not renege on a deal that they agree to.

The EU is still taking a risk negotiating CETA with Canada. This is because the legal validity of the provinces’ commitment to implementing an agreement is unclear. What kind of legal recourse would the EU have if one or more of the provinces refused to implement parts of the agreement? Since I am no jurist, I cannot answer this question, but I am sure that EU negotiators are trying to put as many safeguards as possible into the agreement (especially in the dispute settlement mechanism) in order to deal with this risk. These safeguards are equally important for Canada. The last thing that Canada wants is for the EU to impose ad hoc trade and investment sanctions because a province is not implementing CETA provisions. What is to say that such remedies would target only the uncooperative province? Ultimately, defection by one province could unravel the whole deal. Such uncertainties would be very bad for business. If CETA’s objective is to increase trade and investment, then it would be best to remove as much uncertainty as possible beforehand, since business abhors legal vacuums. Otherwise, to paraphrase W.P. Kinsella, even if we build it, they may not come.

Addressing Michael Hart’s main concern with CETA, the other important condition for successful negotiations is that the deal must not harm the competitive position of Canadian business in the US market. This means that any attempt to harmonize laws, rules, standards, regulations and procedures cannot be to the detriment of Canada’s economic relationship with the United States. This is a “red line” for Canada. If the Europeans are thinking that CETA is a stepping stone to a wider transatlantic agreement with the US, then one might see this condition as not being very restrictive. It may be naive to think, however, that the Europeans will be willing to compromise in the short run with respect to CETA in order to increase the odds of a deal with the Americans in long run. In any case, any transatlantic deal involving the US is unlikely to be feasible before 2021, after the 2020 presidential election.

In addition to the economic benefits identified above, CETA could provide Canada with its best opportunity to create a common market inside its borders, making real the ambitions associated with the provinces’ Agreement on Internal Trade. It is ironic that a state like Canada does not have internal economic integration while the EU, with 27 member states, does (even though it is far from perfect). If all 10 provinces committed to CETA, then they would have to harmonize or mutually recognize laws, rules, standards and procedures not only with Europe but also with each other. At present, only Alberta and British Columbia have a comprehensive internal Trade, Investment and Labour Mobility Agreement (in effect since April 2007), which Saskatchewan decided to join in March 2009 (it is now known as the Western Economic Partnership). Ontario and Quebec are in the process of developing an economic partnership, and they signed the Ontario-Quebec Trade and Cooperation Agreement in September 2009. Hopefully, the CETA negotiations will ensure that these economic partnership agreements are compatible with each other and do not act as regional fortresses inside the Canadian federation.

CETA also highlights the institutional weakness of federal-provincial relations when it comes to negotiating international agreements that touch upon provincial jurisdictions. In fact, Canada has no formal mechanism for negotiating such deals, while the EU has the Council of Ministers, the European Parliament and the European Commission, as well as very elaborate rules for negotiating and ratifying international agreements. Canada’s weakness in this regard was made clear at the UN Climate Change Conference held in Copenhagen last December, when Quebec acted independently of the federal government, to the latter’s dismay.

The Council of the Federation, created in 2003, is a promising basis for developing an institutional mechanism for coordinating the provinces’ and territories’ negotiating positions. As such, it could become like the Council of Ministers in the EU; however, it needs to go further than a meeting of premiers twice a year. Ministers from various departments should meet on a regular basis in between the premiers’ meetings, just as the EU’s Council of Ministers meets every week, on foreign affairs, transport, environment, etc. Moreover, again as in Europe, the Council of the Federation could benefit from having permanent representatives from the provinces to prepare ministers’ meetings and interact with federal government officials on matters that touch all the provinces and the territories, such as the negotiation of international agreements that involve provincial jurisdictions. Indeed, it is surprising that the Council of the Federation has not been used as the institutional springboard for the provinces to get involved in the CETA negotiations. Instead, each province decided to send its own representative. To what extent these provincial negotiators coordinate their positions beforehand remains unclear; however, it is likely that there is little, if any, coordination.

Although it may be too late to use the context of the CETA negotiations to develop an effective institutional mechanism for coordinating Canada’s federal and provincial and possibly territorial positions in international negotiations, Canada’s political leaders cannot afford to wait for the next set of international negotiations to devise such a coordinating mechanism. With globalization increasingly pushing to the international level the governance of issues that were once considered solely domestic — and thus in provincial jurisdiction — Canada must be institutionally prepared to take a strong common position and ensure commitment at all levels of government to international agreements. Otherwise, we run the risk of losing our ability to interact economically and politically at the international level.

This article is based on a presentation he gave at Carleton University’s Centre for European Studies in November 2009.

Photo: Shutterstock