In the sunny, uplit days following Barack Obama’s election, reform of climate policy was perhaps the most anticipated promise in the agenda of hope that would change not just America but the world. Yet two years later, it does not feature in the transformational reforms on health, banking, the new arms reduction treaty with Russia and the end of “don’t ask, don’t tell” for gays in the military.

It is a cautionary and still unfinished tale on the limits of presidential power and the realities of American politics and politicking. Canadians should pay heed. Geographic propinquity means joint stewardship of our shared commons. Energy is our top export to the US. The pricing of carbon, the environmental regulation of industry and the management of grids and pipelines directly affect our interests.

“Energy we have to deal with today…right away,” replied Barack Obama when asked to rank his domestic priorities in the presidential debates. Obama promised to slash carbon emissions to 1990 levels by the year 2020 and impose an economy-wide cap-and-trade program that would aim to reduce emisions, by mid-century, by 80 percent. His message seemed to match the American mood.

In the public mind, “protecting the environment” had surged in annual Pew survey rankings for 2006, 2007 and 2008, with 56 percent of Americans identifying it as among their top 10 priorities. Meanwhile, in a rebuff to the Bush administration, the Supreme Court, in a landmark decision in April 2007, ruled that the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has the right and responsibility to regulate greenhouse gases in order to combat global warming.

“Delay is no longer an option,” said the president-elect in his first recorded message. “Denial is no longer an acceptable response.”

“And to those nations like ours,” President Obama continued in his January 2009 inaugural address, “we say we can no longer afford indifference to the suffering outside our borders, nor can we consume the world’s resources without regard to effect.” Weeks later, in his first address to Congress, he vowed to double renewable energy in three years and promised that the stimulus package would include multibillion-dollar investments for solar, wind and biofuels, along with “clean coal.” “Send me,” he urged Congress, “legislation that places a market-based cap on carbon pollution and drives the production of more renewable energy in America.”

The humbled Republicans signalled that they were ready to act. In their response to the presidential address, Louisiana Governor Bobby Jindal described energy reform as a means of containing prices that had climbed to record levels at the gas pumps during the previous summer.

“We need,” said Jindal, “to increase conservation, increase energy efficiency, increase the use of alternative and renewable fuels, increase our use of nuclear power, and increase drilling for oil and gas here at home.”

The February 2009 stimulus package, the biggest in American history at $787 billion, doubled the budget for the Department of Energy, headed by former Berkeley Laboratory director Steven Chu. Chu, EPA administrator Lisa Jackson and Council on Environmental Quality chair Nancy Sutley all received rapid unanimous senatorial consent for their appointments. Chu had unassailable scientific credentials as a Nobel laureate. Jackson had served as chief of staff to New Jersey Governor Jon Corzine and commissioner of the state’s Department of Environmental Protection. Sutley was Los Angeles deputy mayor for the environment. White House “energy czar” Carol Browner had been Bill Clinton’s EPA administrator throughout his two terms. Jackson, Sutley and Browner were experienced, committed and politically savvy, although for them environment is a religion, and none of them had any business experience. Yet, armed with popular support, judicial backing and enhanced Democratic majorities in both the Senate and the House, the President seemed to have climate reform within his grasp.

Canadians should pay heed. Geographic propinquity means joint stewardship of our shared commons. Energy is our top export to the US. The pricing of carbon, the environmental regulation of industry and the management of grids and pipelines directly affect our interests.

The House of Representatives took the first step when Californian Henry Waxman elbowed his way into the role of legislative helmsman. A long-time advocate of action on the environment, he was instrumental in the passage of the 1990 acid rain cap-and-trade law. With the tacit support of Speaker Nancy Pelosi, Michigan’s John Dingell, avowed champion of the auto industry, was manoeuvred out of the Energy and Commerce Committee chairmanship. With co-author Ed Markey, the Waxman-Markey bill passed the House (219-212) at the end of June 2009. President Obama hailed its passage as “the moment when we decided to…reclaim America’s future.”

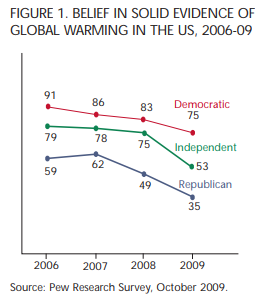

But it was legislation as sausage making. Replete with offsets and credits, it had another 300 pages added to it at 3:09 a.m. on the day of its passage. One pundit described the 1,200-page bill as “so complex and jerry-built that even its supporters can’t know how, or if, it will work.” Parsing the votes and leaving New York and California out of the equation, there was less than majority support, even in Democratic territory. The division had a lot to do with whether a region depended on coal for electricity and/or with the fragile state of many local manufacturing industries. The House debate and daily crossfire coverage in the media also sharpened the partisan public divide. A Pew survey in October 2009 showed a significant shift in the balance of opinion among Republicans, with a majority now saying there is no hard evidence of global warming (figure 1). There were also strong regional differences, with majorities in the Mid-West and Mountain West unconvinced of global warming.

The battle moved to the Senate. That chamber, George Washington told Thomas Jefferson, was created to “cool” House legislation, just as a saucer was used to cool hot tea. To ensure “equality,” regardless of population, each state has two senators, and Senate rules require 60 votes out of 100 to avoid a filibuster.

Bipartisan support for climate reform appeared possible. A dozen Republican senators were on record supporting some form of action on climate. In 2003, Republican John McCain and Democrat Joe Lieberman brought forward their cap-and-trade Climate Stewardship Act. It failed (43-55), but it attracted bipartisan support. In June 2008, a majority of the Senate supported mandatory greenhouse gas cap-and-trade legislation proposed by Republican Jack Warner and Joe Lieberman. In addition to the 48 yes votes, six absent senators, including presidential nominees McCain and Obama, entered statements of support.

In June, 2009 a bill that included renewable energy standards passed out of Senator Jeff Bingaman’s Energy and Natural Resources Committee. In December, Democrat Maria Cantwell and Republican Susan Collins introduced a “cap and dividend” bill that included a cap and auction on carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions that would return three-quarters of the revenue to consumers.

The most serious effort, and the one that recognized where the political sweet spot could be found, was that of Senators John Kerry, the Democratic presidential standard-bearer in 2004, Republican Lindsey Graham and Joe Lieberman. Their approach was a tactical lesson in politicking: sit down with the utility and oil companies, the manufacturers and chambers of commerce. Let them have considerable input into the drafting of the legislation, because if you do not, they will spend millions of dollars in advertising to bury you. The US Chamber of Commerce wouldn’t support the bill, but it would not go to war against it. The Edison Electric Institute, representing the utilities, came around. Three of the majors — ConocoPhillips, BP and Shell — that had joined the “Climate Action Partnership” indicated that they would hold back the American Petroleum Institute (API). As the voice of the oil industry, the API had funded a multimillion-dollar campaign against Waxman-Markey, including organizing what critics called “Astroturfing” — events intended to exert pressure on legislators by giving the impression of a groundswell of public opinion.

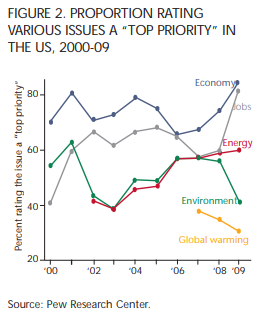

Meanwhile, support for environmental change plummeted, affected, in part, by the skepticism raised about the science of climate change as a result of the East Anglia leaks in November 2009 (figure 2). The shambolic Copenhagen climate conference in December 2009 also resurrected the sense that the US (and the West) was expected to shoulder an unfair burden in terms of both regulatory obligations and reparatory payment: i.e., a transition fund for so-called developing nations. Kyoto ratification had failed years earlier for the same reasons (the “sense of the Senate” vote in 1997 was 95-0).

Notwithstanding the “shellacking,” as Obama himself called it, the lame-duck session of Congress would prove to be one of the most productive in history, with a deal on taxes, passage of the START Treaty, repeal of the “ don’t ask, don’t tell” law and the largest overhaul of food safety regulations in more than 70 years. But nothing on climate reform.

The November 2009 loss of Democratic governorships and the rise of the Tea Party movement, signalled by the January 2010 special Senate election of Republican Scott Brown in Massachusetts, pointed to the end of the Obama honeymoon. Jobs and the economy transcended every other issue. But the passage of health care reform in March 2010 restored the administration’s self-confidence.

The Deepwater Horizon sank in the Gulf of Mexico on April 22, 2010, and for the next five months, until BP sealed the ruptured well, the oil leak was visible to all thanks to a little box, the Spillcam, that the networks inset into television screens. It was the worst environmental disaster in American history. Forty years earlier a blowout off California’s Santa Barbara coast, in December 1969, had galvanized American consciousness and led to legislation creating the EPA in 1970 and improvements in the Clean Air Act and the Clean Water Act. The 100,000 barrels spilled off Santa Barbara equalled less than two days spill from BP.

Meanwhile, the summer of 2010 was the hottest recorded in a century. “In the same way that our view of our vulnerabilities and our foreign policy was shaped profoundly by 9/11,” the President told Politico, “I think this disaster is going to shape how we think about the environment and energy for many years to come.”

The spill killed the “Grand Bargain.” Senators Kerry, Graham and Lieberman were in the final stages of drafting a bill that combined cap-and-trade with an expansion of oil drilling and guarantees for the nuclear industry. The spill made drilling politically toxic for the Democrats, even though a Pew poll in May still showed a majority of the public favoured drilling. Senator Graham left the negotiations and announced his opposition. Facing filibuster and the likelihood of defection by Democrats, Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid announced in late July that there would be no energy legislation before the midterms.

In November, the Democrats lost control of the House of Representatives and six seats in the Senate. Notwithstanding the “shellacking,” as Obama himself called it, the lame-duck session of Congress would prove to be one of the most productive in history, with a deal on taxes, passage of the START Treaty, repeal of the “don’t ask, don’t tell” law and the largest overhaul of food safety regulations in more than 70 years. But nothing on climate reform.

New EPA regulations for greenhouse gas emissions from energy plants and factories took effect on January 2, 2011. Lawyers are busy preparing challenges on behalf of environmental interests, the utilities and oil companies, and 10 states, including Texas, are challenging Washington’s authority. In Congress, there is legislation aimed at curbing or putting a moratorium on the EPA’s authority. We face a “glorious mess,” writes Eric Pooley in The Climate War: True Believers, Power Brokers, and the Fight to Save the Earth (2010).

The divide is more than party polarization. Looking at energy use by state in the last Congress, Michael Barone, editor of the definitive Almanac of American Politics, concluded that for 27 Democratic senators and 100 Democratic House members from the West, the Plains and the South, coal accounts for more than half of their constituency’s energy. It explains, he said, why, when the Senate voted on whether to include cap-and-trade in the 2009 budget reconciliation resolution, 26 Democrats joined the 41 Republicans to raise the bar for passage from 51 votes to 60 and why 44 Democrats voted against Waxman-Markey.

Twenty-five states get at least half of their electricity from coal-fired plants. Clinton and Gore sought a BTU tax, but their “war on coal” failed because coal-state Democrats, led by West Virginia’s late Senator Robert Byrd, pulled the plug. In a “polar bear moment” at the end of his long life, Byrd told the Mountain State to “anticipate change and adapt to it,” but electors chose as his successor Democratic governor Joe Manchin. Manchin’s campaign ad featured him literally taking aim and putting a bullet in the climate change bill.

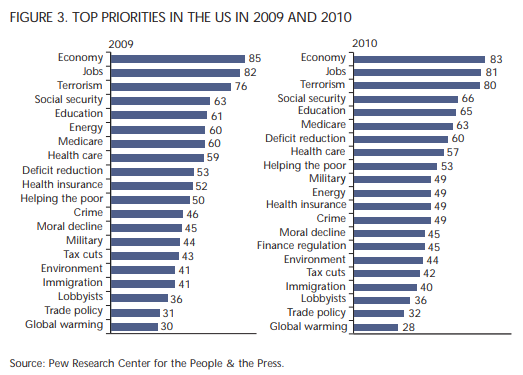

The percentage of Americans who believe global warming should be a top priority began falling even as Obama began his presidential bid. Today, global warming ranks near the bottom of public priorities. Americans are unconvinced of the need for action, especially when they are asked to pay for it.

Cap-and-trade is discredited, for now. It began life in the late 1980s as a Republican idea in the administration of George H.W. Bush, to apply market forces to reduce sulphur dioxide emissions, i.e., acid rain, in coal-burning eastern power plants. Former prime minister Brian Mulroney deserves much credit for persuading first VicePresident Bush and then President Reagan to set in motion the successful cap-and-trade process on acid rain. The flexibility offered by that program was preferable to rigid plant-by-plant command-and-control regulation by the EPA. There were also fortuitous circumstances that made the transition cheaper than many utilities and analysts expected. Contrary to industry’s initial concerns, over time scrubber technology became cheaper. Meanwhile, the deregulation of rail transport made low-sulphur coal from the western US available at a competitive price in eastern US power plants, displacing the locally mined higher-sulphur coal.

Applying cap-and-trade to carbon dioxide emissions will be difficult. In contrast to Unlike sulphur emissions, there is no commercially available and cost-effective technology to “scrub” CO2 emissions out of an industrial plant or a tailpipe. Real carbon emission reductions require significant change in production processes and consumption patterns. The complex trade-offs contained in Waxman-Markey fed fears of Enron-like manipulation, while the label “cap-and-tax” has taken hold in the public mind.

Obama is learning the congressional horse-trading that Lyndon Johnson understood so well, but on climate policy he has yet to persuade Americans of the urgency for action. The percentage of Americans who believe global warming should be a top priority began falling even as Obama began his presidential bid. Today, global warming ranks near the bottom of public priorities (figure 3). Americans are unconvinced of the need for action, especially when they are asked to pay for it. Salience is what makes politicians pay attention, and the public focus is on jobs and the economy. Attitudinal change is hard. Since Richard Nixon, administrations have sought to deal with the energy problem but failed. In his 1979 “malaise” speech, Jimmy Carter got to the heart of the issue when he argued that to face up to the energy crisis, Americans first had to face up to the crisis in their own values, seen in “the growing doubt about the meaning of our own lives and in the loss of a unity of purpose for our nation.” And of course, he lost the 1980 election to Ronald Reagan, by a landslide.

Decarbonizing the global energy system is an epic challenge. The late Nobel laureate Stephen Schneider argued that sequencing is vital, starting with demonstrable steps on a clean power plant and then building support for broader, grander structures like a carbon tax. In reaffirming that the environment remains one of his top priorities, Obama told Rolling Stone in October that he would roll out new policy “in chunks” rather than “some sort of comprehensive omnibus legislation.” He promised to “stay on this because it is good for our economy, it’s good for our national security, and, ultimately, it’s good for our environment.” Climate policy reform is unlikely to be accomplished in one presidency. Doing it in chunks recognizes the realities of regionalism, polarization and the requirement for attitudinal change.

Curtailing America’s largest source of carbon emissions — coal-fired electricity — will also be driven by other factors. Many of the most carbon-intensive plants are nearing end-of-life. A host of other factors, including the impending EPA regulations on mercury and other air pollutants and access to reserves of natural gas, may hasten conversion to cleaner-burning fuels, even in the absence of carbon regulation.

A necessary step will be to reframe the debate from one of a pollution problem to one of an innovation opportunity. We don’t yet have the technology to give us clean energy on a large scale, but the US is well positioned to drive the demand for it. There is a growing chorus within industry and the environmental movement calling for an energy revolution. Energy alternatives — solar panels, biomass, wind mills and tidal power — are part of the solution. So is conservation.

Curtailing America’s largest source of carbon emissions — coal-fired electricity — will also be driven by other factors. Many of the most carbon-intensive plants are nearing end-of- life. A host of other factors, including the impending EPA regulations on mercury and other air pollutants and access to reserves of natural gas, may hasten conversion to cleaner- burning fuels, even in the absence of carbon regulation.

State-inspired processes, including the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative in the North east and the Western Climate Initiative, which also involves four Canadian provinces, will continue to innovate and reform. Environmentalists look to California, where an oil-industry-inspired initiative to roll back climate change legislation failed in the November midterms. The counter-effort rallied Democrats and Republicans, including former secretary of state George Shultz. In December, the California Air Resources Board voted to adopt cap-and-trade regulations for California’s global warming law. Other states are moving forward through legislation and regulation. Technology funds for clean energy development are growing in popularity.

Arguably, Obama has already accomplished part of what he set out to achieve. The stimulus and other financial measures are putting close to $100 billion into research and development. Why not take on the mantle of energy innovator and, with support from the Pentagon and industry, frame it as an issue of national security? America is still highly dependent on energy imports, but what if that could be balanced by new export opportunities for cleaner energy technologies, products and services?

For Canadians, the American drama is more than a spectator sport. Our interests in it are huge. Decisions relating to smart grids, low-carbon fuels, pipelines and renewable energy standards for hydro power matter to our continuing prosperity. We’ve harmonized with the US on tailpipe emissions, we partner with it on projects like carbon sequestration and through the Clean Energy Dialogue, but with differences in our energy mix, our strategic goal must continue to be “compatibly Canadian,” rather than an American clone.

We possess intellectual power and ideas in places like the National Roundtable on Environment and the Economy through industry associations like the Canadian Council on Chief Executives and the Energy Policy Institute of Canada; at the Canada School for Energy and the Environment; and in our environmentalists, including the Pembina Institute and Pollution Probe. The Boreal Forest Agreement is proof that industry and the environment can be creatively productive. Let’s take this talent on the road and show the world that we can be a global superpower in climate reform.

Photo: David Peterlin / Shutterstock