(Version française disponible ici)

The global political landscape is shifting from the international collaboration that led to the Paris Agreement 10 years ago to more nationalistic policies.

This highlights one of the most intractable problems of addressing climate change – the “collective action problem.“ Optimal global outcomes require international collaboration, but individual countries are inclined to take paths that can have the opposite effect.

For instance, while phasing out the global use of fossil fuels as an energy source is an incontrovertible requirement of addressing climate change, economic interests and energy security concerns compel some countries to continue or expand the extraction and use of fossil fuels, sometimes in clear violation of their express climate policies.

This is happening at a time when the catastrophic consequences of climate change are felt and seen across the world and when mitigation seems an increasingly daunting challenge.

As bleak as things may look, this could be a historic opportunity to renew and reshape climate policies. Two main steps need to be taken – admit that the Paris Agreement approach has failed, then shift action from mitigation to resilience and adaptation.

For instance, instead of decarbonizing low-performance buildings as our current policies and codes allow – and sometimes encourage – we have to focus on the design and construction of high-performance buildings that ensure occupants are safe from the consequences of climate change, such as rising temperatures, heatwaves, power outages, etc.

Current mitigation efforts are failing

Despite decades of dedication and hard work, the world is far from meeting the emission-reduction targets of the Paris Agreement.

Under its terms, Canada committed to reducing its emissions by 30 per cent below 2005 levels by 2030. However, by 2022, our greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions had decreased by a mere 7.1 per cent. Since the 2020 dip induced by COVID-19, our emissions have in fact been rising. Things are not looking any better globally. Between 2005 and 2021, global GHG emissions increased by 24 per cent.

So, the first step toward a more successful approach to climate policy is to acknowledge the failure of the Paris Agreement and national policies under it. This includes the methodological and conceptual flaws of the agreement as well as the practical shortcomings in its implementation.

This admission of failure is by no means an attempt to deny or discount the progress that has been made – particularly in renewable energy generation, and the electrification of buildings and transportation – but rather an objective assessment of GHG emissions against the agreement’s targets.

The second step is to abandon some of the increasingly elusive mitigation aspirations in favour of preparing for the ostensibly unavoidable consequences of climate change. While the concepts of adaptation and resilience have gradually seeped into the discourse, they are rarely the focus of climate policy. Furthermore, they are mostly considered for extreme events, as opposed to a shifting baseline (the “new normal.”)

Both of these steps would be extraordinarily difficult, not the least because of the emotional toil they may entail for the people involved in the work. But the transition is both possible and necessary.

Three observations must guide the transition to a new paradigm of climate action.

First, to the best of our knowledge, average world temperatures will continue to rise by at least 1˚ C above pre-industrial levels by 2050, regardless of what we do about GHG emissions.

Second, even if Canada went zero-emissions overnight, it would have virtually no effect on the overall level of global emissions and thereby climate change.

Third, a shift of focus from mitigation to adaptation and resilience means a reconsideration of objectives and priorities as well as a reallocation of resources.

Global temperatures will continue to rise

Not much can be done about rising temperatures in the next quarter century. A hallmark of the colossal work that the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has been doing to track, model and predict climate change is the so-called representative concentration pathways (RCPs) – hypothetical projections of greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere based on different scenarios of emissions caused by economic activity.

Notably, within the margins of error associated with those projections, all emissions scenarios will have essentially the same outcome up to about 2050 – most likely more than a 1˚ C warming on average, corresponding to temperature rises of at least 2˚ C in Canada.

It is only past the century’s midpoint that different emission scenarios start to show diverging effects. This observation begs the question: What are we doing to prepare for that level of (almost certain) warming in Canada over the next 25 years?

What Canada does doesn’t matter. Or does it?

Canada’s GHG emissions are a tiny part of total global emissions – 1.4 per cent in 2021. Obviously, eliminating that small fraction will not mitigate worldwide climate change.

More importantly, emissions from several other countries with much higher shares are rapidly rising and there is little that Canada can do to reverse that trend. This crucial point has been widely known for many years but has been disregarded with pretentious claims of “leading by example,” moral obligation, etc.

On the other hand, it appears that a shift from mitigation to adaptation and resilience would automatically resolve, or at least circumvent, the collective action problem.

While there is little that Canada can do to stop or slow down global climate change, action to prepare for its consequences is almost entirely in our hands. Even more importantly, these preparatory actions can, and must, be taken at regional and community levels.

Again, the building sector is an instructive example. It is the provinces, cities and other communities that regulate construction and therefore can trigger a transformation that ensures climate-resilient buildings.

We have a pretty good idea of the consequences of 2 C warming in Canada. We also have the knowledge and technology to best prepare for those consequences. What is missing is policy to drive the wide implementation of the necessary measures.

A reallocation of resources is needed

A main challenge for effective climate action is the allocation of limited time and money. Over the past few decades, the climate action community has fought hard for and won significant resources – albeit not commensurate with the immensity and urgency of the task – to advance the overarching goal of reducing emissions.

Fortunately, the proposed paradigm shift can leverage much of the work already underway, such as the diversification of energy sources, distributed power generation, energy storage, etc. Nevertheless, resources are limited, so moving to adaptation and resilience would necessarily be at a cost to the current single-minded focus on decarbonization.

On the other hand, a fresh approach that entails abandoning disproven goals and means would free us from the continual revision and modification of the emission-accounting schemes and constantly moving the goalposts of an over-bureaucratized climate policy.

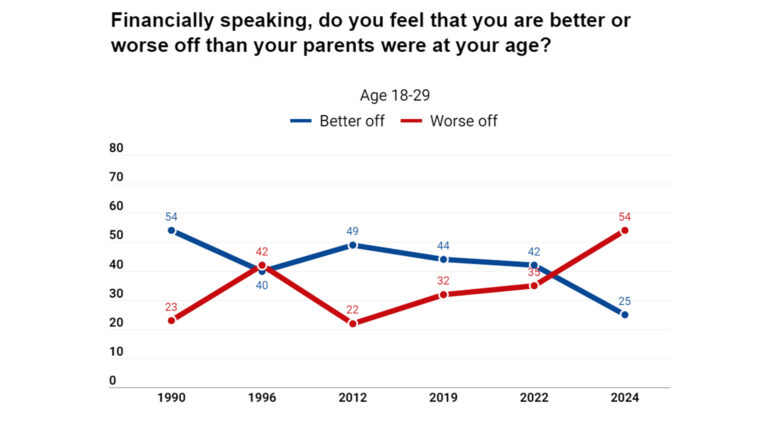

Moreover, the new paradigm can unlock another invaluable resource – the passion and dedication of a younger generation who feels betrayed and enraged.

Acknowledging those sentiments and their legitimacy – instead of making more fantastical promises of change, aptly characterized by Greta Thunberg as “blah blah blah,“ – can be the first step toward alleviating that anxiety and redirecting that rage into reparatory action. We cannot afford to alienate those who will have to lead climate action in the future.