In 2021, the federal government pledged to build a diverse, equitable and inclusive public service by hiring and promoting more Black, Indigenous and racialized people.

Historically, and with some high-profile exceptions, Ottawa’s constellation of government departments and agencies, as well as government-financed institutions, have been lethargic in recruiting and retaining Black minorities.

The problem is cultural. For decades, the sought-after Canadian perspective comprised the narratives of two settler-colonial regimes, English and French, with strong European and American influences. These were overlaid in the last 40 years with a thin veneer of multiculturalism and, more recently, attention to Indigenous issues.

Settler-colonial states, including Canada, adopted imperial perspectives that disrespected peoples of colour and their views. In these scenarios, people from troubled parts of the world – and Indigenous Peoples – simply failed the European civilizing mission and were therefore the authors of their own misfortunes.

Governments and commentators dismissed Black slavery and its consequences as a necessary contribution to progress, rather than a major contributor to global inequality and injustice, and dismissed Black people as inferior.

Canada needs education that takes a deep, honest look at the past.

Black history month in February provides an opportunity for federal and provincial governments to focus on the means and methods to reverse long-standing prejudices against Black people in Canada.

In 2020, Statistics Canada reported that 63 per cent of Black people surveyed experienced discrimination in the five years prior to the pandemic or during COVID-19 – nearly double the proportion of the white population (32 per cent).

Many forms of racism

There are statistics, and then there is the lived experience of discrimination that keeps Black people and some other minorities from seamless integration into the ranks of the public service and Canadian society.

Writer David Ess describes how he was routinely called the N-word at his middle-class Ottawa high school. Tonni Brodber returned to Trinidad from Ottawa after being told her skin was “the colour of shit,” among other insults. In Ontario, young Black nurses spoke out in a 2022 report about deeply entrenched racism on the job.

The comments I have heard in 35 years of living in Ottawa include: “It’s a good neighbourhood, no Blacks.” “Jamaicans are responsible for crime in Canada.” “If the darkies give you trouble, shoot them.” “Africans should go back up the trees.” “We are better than those Third World countries.” The area where I live is a blend of Caucasians and people of colour and there is ongoing discussion and confusion over race issues.

The problem also permeates the public service. The federal government’s 2019 anti-racism strategy has begun to address the consequences of systemic racism in the public service, but much more education and training are needed.

Black public servants are locked in a three-year legal battle with Ottawa, with no end in sight

The 2023 report of the federal auditor general noted that in six organizations representing 21 per cent of the public service, there is “little evidence that actions to improve inclusion in the workplace are making a difference for racialized employees.”

The report also notes that none of the organizations analyzed data about how they handled complaints of racist behaviour and related power imbalances – despite racialized employees’ concerns about existing processes. Racialized employees who speak out may be labeled “loose cannons.”

The transatlantic slave trade

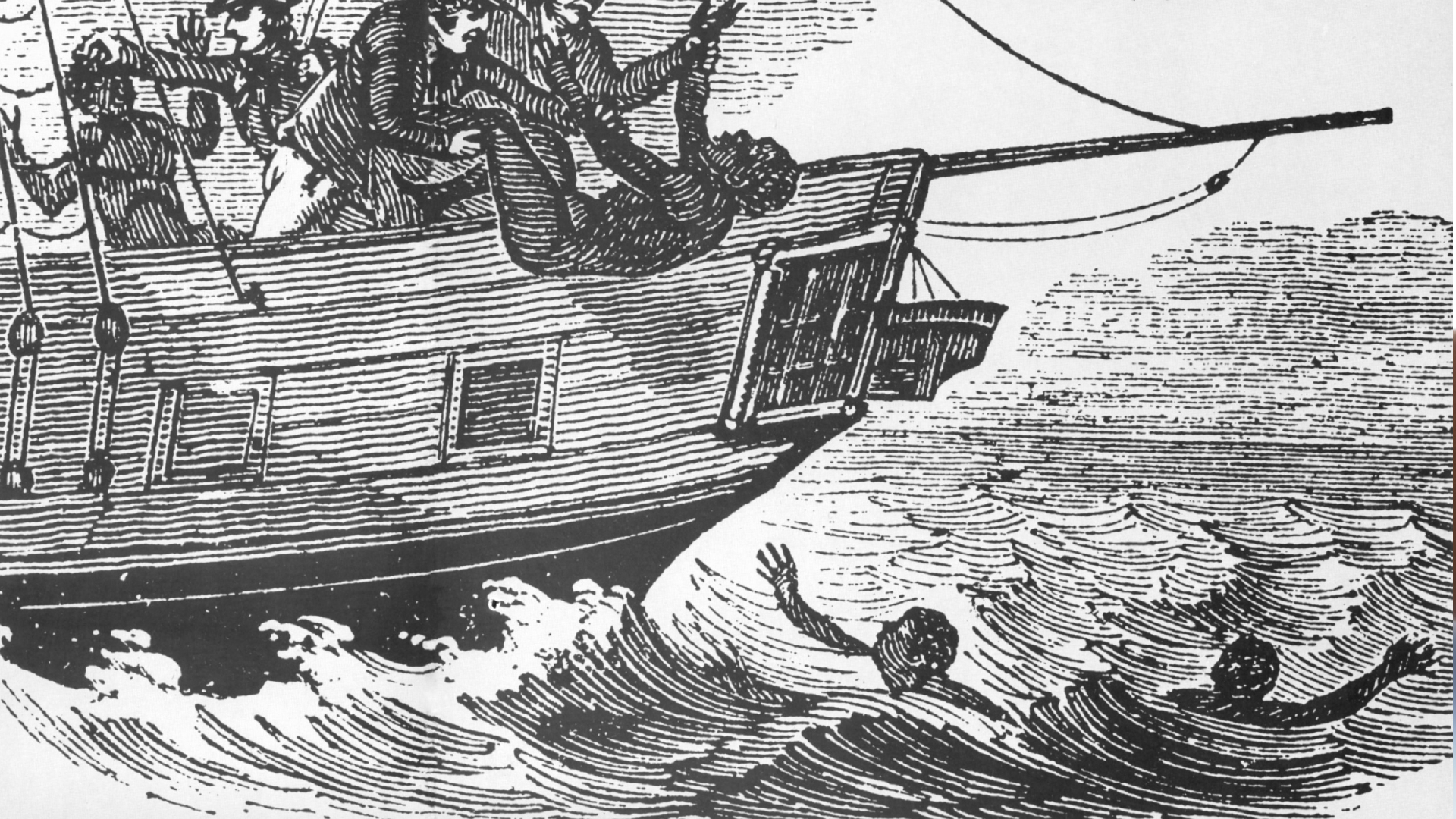

Negative attitudes toward Black people did not emerge spontaneously. For four centuries, Western belief in Black inferiority and disposability rationalized the transatlantic slave trade.

An estimated 10-12 million Africans were shipped to the New World. Around two million fewer landed. Men, women and children were packed like sardines onto disease-ridden slave ships. Sick, elderly and rebellious people were thrown overboard to feed the sharks or drown. On arrival, many New World planters worked enslaved people to death.

In Brazil, Barbados, Canada/New France and Jamaica, the average life expectancy of an adult worker during slavery was well under 30 years. In Canada, which had about 4,000 enslaved people of African descent, it was 25 years.

Only in the U.S. did the slave population increase, possibly a result of higher birth rates. In the Caribbean and Brazil, the numbers of people emancipated in the 19th century were a small fraction of those that had been brought to the New World.

Emancipations in the 19th century didn’t eliminate old stereotypes, dirty words or the assumptions of inferiority and disposability. Across the Western Hemisphere, including Canada, people of colour faced legislation, public policy and segregated education systems that marginalized and discriminated against them. The 1960s U.S. civil rights movement led the world in reasserting Black human rights.

In Canada, formal protection from racist education, employment and housing restrictions began to appear only in the 1950s and 1960s. The Black Lives Matter movement points out that old prejudices linger in Canada, a country that often believes it is racism free.

Black studies need a revival in Canada

Ignoring the story of Black slavery leads to erasure of history and supports prejudice.

“You weren’t the only slaves,” an Ottawa manager recently told an employee, according to a complaint filed by the employee. A Nigerian writer popped up to say that here great-grandfather sold slaves but he should not be judged by today’s standards. “Well, it was necessary and helpful for Africa,” a public servant “explained” to me.

These are fallacies.

There are decades of studies that show how the slave trade damaged Africa. A recent Harvard study noted a correlation between the most politically and ethnically fragmented parts of Africa and the areas with the highest number of kidnapped people centuries ago.

Erasing the story of Black slavery also obscures the enormous contribution of enslaved Africans to Western capitalism. The profits of slavery provided the seed money for industrial revolutions, built great stately homes, supported emerging banking systems, universities and agricultural revolutions in crops such as sugar, cotton and tobacco, as well as developments in technology.

The ongoing failure to acknowledge enslaved peoples’ contribution to global progress (and the price they paid for it) hurts the drive for equality today.

In Ottawa, the stated goal of increasing Black representation in public service management is necessary but insufficient. Successful bureaucrats rarely challenge dominant narratives.

There is a wave of Black studies programs at several Canadian universities, driven by demand from Black Canadians.

Ottawa should view those programs as a means of integrating the story of Black slavery, and the wider issue of Black history, into a Canadian perspective. Their findings and teachings could be incorporated into the professions and used for training the public service.

At a minimum, the teaching of progress, whatever the discipline, could usefully acknowledge the capital accumulated by the theft of humans from Africa and the theft of indigenous lands in the Americas.

Community is built on understanding. Canada is an increasingly diverse country where “driving while Black” is a scourge. The police, like most Canadians, need more education and training to decolonize their perceptions of Black people.

The Museum of Human Rights in Winnipeg leads the way in discussing the story of Black slavery. Others should follow with permanent exhibitions. Anti-racism programming in schools is also important.

Efforts, such as a memorial to enslaved Africans and their contribution on Dundas Street in Toronto – the site of a current renaming controversy – might also help provide perspective.