Wildlife is central to the Canadian identity. From Indigenous communities to the urbanites of our largest cities, an overwhelming majority of Canadians want the federal government to protect and restore species at risk of extinction.

The principal federal instrument that provides for this protection is the Species at Risk Act (SARA), passed by Parliament in December 2002. SARA’s purposes are to prevent extinction, to recover species currently threatened directly or indirectly by humans and to manage other species to prevent them from becoming endangered or threatened in the future. Judged against these objectives, SARA has underachieved because of withering political interest and weak policy prescriptions.

The federal cabinet decides which species are listed under SARA, a statutory process that begins with the government’s receipt of assessments from an independent national advisory body called COSEWIC (Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada). COSEWIC advises the listing of a species when there is compelling evidence of a dramatic reduction in abundance caused by threats such as habitat loss, overexploitation, pollution, nonnative species and climate change.

More than 520 Canadian species (plants, birds, mammals, fishes, amphibians, reptiles, insects, lichens) have been listed under SARA. Some of these now number in the tens of individuals (such as the northern spotted owl); many others have experienced declines of more than 90 percent, such as the 12-metre-long basking shark, Canada’s largest fish.

Despite initial good intentions, all has not gone well in protecting and recovering species at risk. The listing-decision process ground to a halt after 2010; COSEWIC continued to communicate its advice but the government did not act on it. Backlogs in finalizing recovery strategies for previously listed species have been severe. SARA’s List of Wildlife Species at Risk has long been biased against marine and northern species. Limited use has been made of SARA’s conservation agreements to broaden the engagement of citizens, business and civil society in stewardship activities. Few quantifiable benchmarks exist for evaluating recovery successes (and failures).

However, recent efforts by Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC, which has primary responsibility for SARA) suggest a renewed commitment to protecting species at risk. The Minister has reinvigorated the stalled listing process and dramatically accelerated the rate of production of proposed recovery strategies.

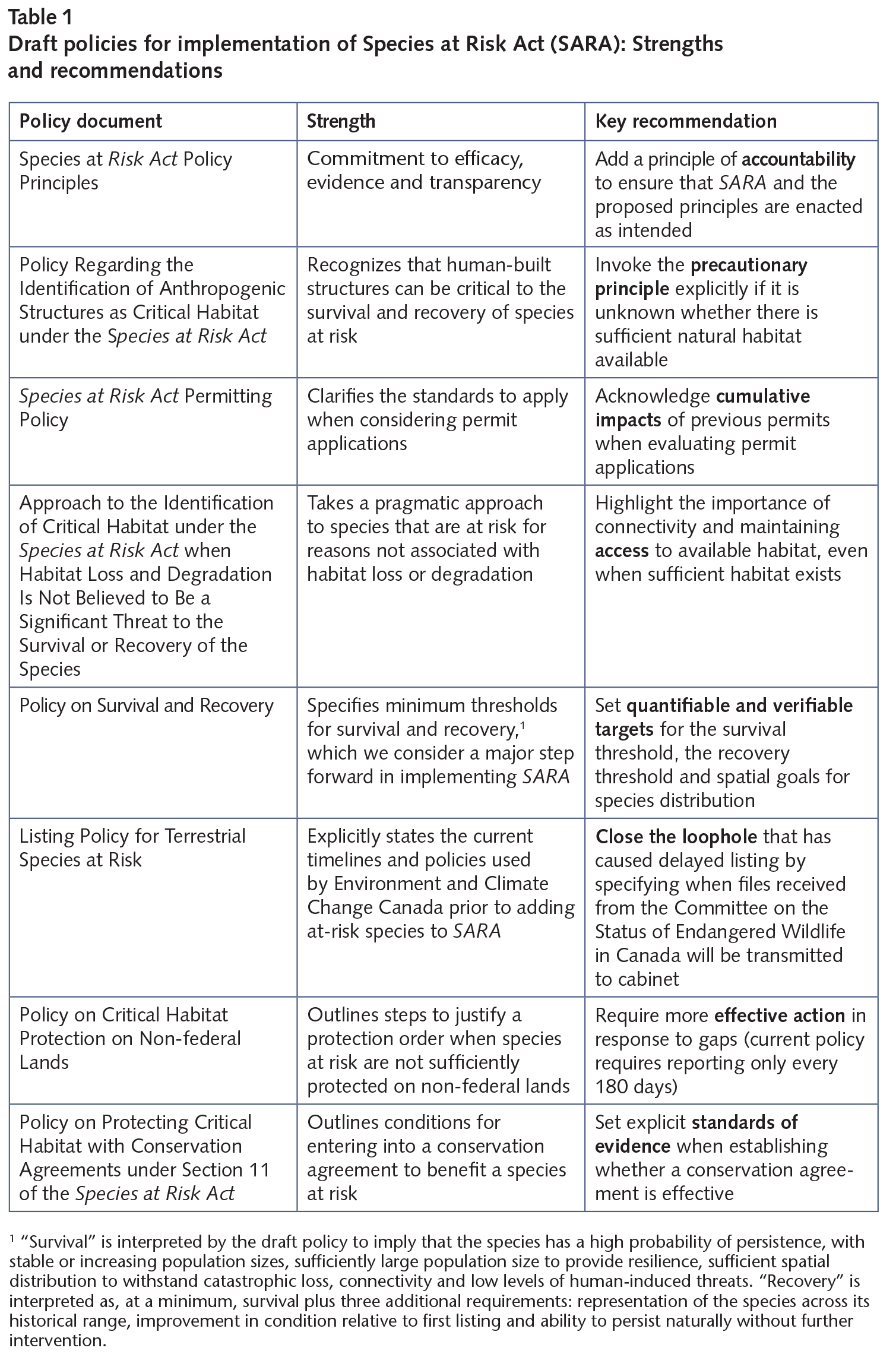

At the policy level, ECCC has released a suite of eight draft documents for public consultation. These aspirational documents provide greater clarity, rigour and guidance for a number of key decision elements under SARA. If comprehensively and rigorously brought into effect, they will almost certainly strengthen the implementation of SARA and increase the chances of effective protection and recovery of species at risk.

For example, the draft Policy on Survival and Recovery addresses a surprising ambiguity in the legislation: SARA does not clearly differentiate between what it means for a species to “survive” and what it means for it to “recover.” The new draft policy makes this distinction clear. It states explicitly that the goal is not to keep endangered species endangered (survival) but to build toward self-sustaining populations (recovery). Moreover, this policy and several others explicitly recognize the importance of the precautionary principle in light of scientific uncertainty: when data are lacking about the efficacy of alternative actions, recovery objectives will “err on the side of precaution by not foreclosing opportunities for recovery.”

Despite these laudable attempts to improve SARA implementation, critical issues remain in the draft documents. We have outlined in table 1 some of the strengths we find in the documents as well as several of our concerns and recommendations, and three issues are highlighted here.

An evidence-based approach

The first — the commitment to an “evidence-based approach” to decision-making as a policy principle — might seem self-evident and uncontroversial. The draft policies are, after all, intended to “emphasize sound approaches that are supported by credible scientific and technical data, aboriginal traditional knowledge and community knowledge.” But who decides what constitutes a “sound” approach? What constitutes “credible” data and knowledge?

An evidence-based approach entails the gathering and weighing of evidence. But it also requires specifying how that evidence will be used (presumptions), specifying the thresholds that must be met by evidence to influence decisions (standards of proof) and specifying who has responsibility for demonstrating that these thresholds are reached (burden of proof). Here, clarity is key: even with the same scientific evidence, decision outcomes can differ dramatically depending on what the presumption is, what the standard of proof is and who bears the burden of proof. Indeed, these factors figured prominently in four judicial reviews of SARA implementation, all of which focused on what evidence should be gathered and how it should be used.

To improve clarity, the draft SARA policy suite should state what is meant by an evidence-based approach. As a concrete first step, it could specify that ECCC’s evidence-based approach, when it receives advice from COSEWIC, will adhere to the principles and guidelines established in a Council of Science and Technology Advisors report on just this issue (Scientific Advice for Government Effectiveness, or SAGE), approved by cabinet in 2000.

Listing delays

A second issue concerns listing delays, which ought to be addressed in the draft Listing Policy for Terrestrial Species at Risk. For a species to be protected under SARA, it must first be assessed by COSEWIC. Listing advice from COSEWIC is then provided to the minister of ECCC, based on the best available information on the biological status of each species, including scientific knowledge, community knowledge and Indigenous traditional knowledge. The minister may then consult with provincial and territorial governments, Indigenous organizations and wildlife management boards, industry, civil society and citizens. These consultations in turn inform the minister’s recommendation to cabinet, which ultimately decides whether to accept or reject COSEWIC’s advice (or, in rare cases, to send the assessment back to COSEWIC).

More than 100 species now await listing decisions. Some have been waiting for more than a decade, caught between scientifically proffered advice and politically motivated procrastination. During the first few years following SARA’s proclamation, the listing process was usually completed within 24 months. Since then, the time taken to act upon COSEWIC’s advice has ballooned. The longer the listing delay, the longer a species awaits legal protection, thereby increasing the chance of further decline, causing its recovery prospects to fade and recovery costs to mushroom. Birds such as the bobolink, the barn swallow and the eastern meadowlark — declining at rates of about 20 percent per decade — are among those trapped in “listing limbo.”

Having species languish in this legislative purgatory was clearly not the intent of SARA’s architects. It has come about because there is no provision in SARA that specifies a timeline for the environment minister to send COSEWIC’s advice to cabinet. This has resulted in ministerial discretion to determine when, and in practice if, a COSEWIC assessment is communicated to cabinet. In 2008, Parliament’s Standing Joint Committee for the Scrutiny of Regulations characterized this discretion as a “defect” of the Act, concluding that “failure to provide for the delivery to, and receipt of, an assessment by the Governor in Council [the cabinet] reflects an unintended gap in the scheme established by the Act.”

Unfortunately, the proposed Listing Policy for Terrestrial Species at Risk fails to fix this gap, raising the spectre of continued or prolonged listing delays in the future. To close the loophole, at least at the policy level, ECCC should revise this draft policy to specify a timeline for sending COSEWIC’s assessments to cabinet, consistent with Parliament’s original intent that listing action be taken within a fixed period of time. Only by so doing can the current minister fulfill the explicit directive in her mandate letter to protect species at risk “by responding quickly to the advice of scientists.”

An absence of targets

A third critical issue relates to SARA’s overarching goal of improving the condition of species at risk. While the draft Policy on Survival and Recovery is scientifically sound and clarifies the distinction between survival and recovery, it does not require that recovery strategies include quantitative targets. Currently, most recovery strategies set vague targets (such as “increase the number of individuals” without setting a quantitative goal). This lack of specificity makes it difficult to track recovery progress and to determine whether protection and recovery actions are effective. Indeed, the absence of quantitative targets is not unique to the draft Policy on Survival and Recovery; other documents in the policy suite are also missing this element. As a remedy, ECCC should establish measurable targets for defining thresholds for species survival and recovery, the extent of protection on nonfederal lands, and the quantity and quality of critical habitat implicated in conservation agreements.

Establishment of quantitative targets will require more effective use of the monitoring programs that should accompany recovery efforts. Moreover, in keeping with the government’s commitment to greater openness and transparency, all data gathered in support of SARA-mandated actions should be freely available unless there are compelling reasons for restricting it. This will allow any Canadian to independently assess how species are doing, making it possible to determine which protective actions and policy approaches have the greatest impact on Canada’s species at risk.

David Anderson, Canada’s longest-serving minister of the environment (1999-2004), described the long process that culminated in the passage of SARA as being akin to pushing a massive boulder uphill, very slowly. Over the past decade, waning political will and a lack of precise, prescriptive implementation policies have resulted in significant slippage. The recent suite of draft policies — suitably amended and rigorously implemented — should go some way toward ensuring a smoother, if still slow, ascent to the summit of full species protection and recovery.

Photo: Northern Spotted Owl. AP/Tom Gallagher

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.