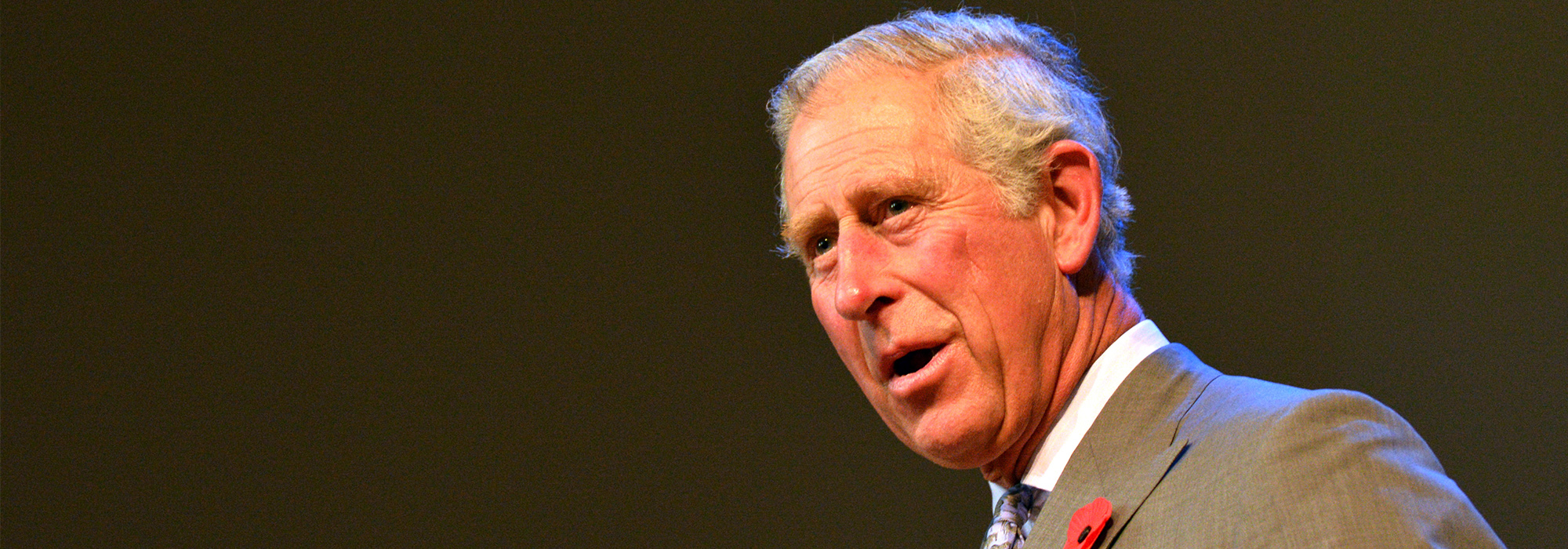

A Royal advocate

Upper Tribunal, United Kingdom

September 18, 2012

Mr. Rob Evans, a journalist who has worked for the Guardian, has asked to see correspondence between Prince Charles and United Kingdom government ministers. Mr. Evans contends that disclosure of the correspondence will be in the public interest, at least to the extent that the correspondence involves “advocacy” on the part of Prince Charles… It is common ground that in the present case entitlement to disclosure broadly depends on the answer to a core question: will disclosure — including any breach of confidence or privacy that disclosure will involve — be in the public interest?…

We stress at the outset what we are not concerned with. We do not define what Prince Charles is entitled to say to government…In the United Kingdom strong views are held by many people for and against the monarchy and for and against the approach which Prince Charles has taken to his role. Some will be horrified at any suggestion that correspondence between government and the heir to the throne should be published. They fear, among other things, that disclosure would damage our constitutional structures. Others may welcome such disclosure, fearing among other things that without it there will be no real ability to understand the role played by Prince Charles in government decision-making…

[W]e conclude that under relevant legislative provisions Mr. Evans will, in the circumstances of the present case, generally be entitled to disclosure of “advocacy correspondence” falling within his requests. The essential reason is that it will generally be in the overall public interest for there to be transparency as to how and when Prince Charles seeks to influence government…

Prince Charles is the heir to the throne, not just of the United Kingdom, but of other countries as well. He has acknowledged that there is no established constitutional role for the heir to the throne. In the absence of any such established constitutional role, he has chosen a role of seeking to make a difference — not as king, but as Prince of Wales. As part of this role he explained in his Annual Review 2004 that he has been “identifying charitable need and setting up and driving forward charities to meet it,” and has also been promoting views of various kinds. It is those two features of Prince Charles’s activities which in our view provide a touchstone for identifying “advocacy correspondence…”

Confidential interaction between government ministers and others, in a context where those others are seeking to advance the work of charities or to promote views, would generally be disclosable — especially where those others have privileged access to ministers. Our conclusion is that special factors concerning Prince Charles will not — under the legislation governing the requests in this case — generally result in a different consequence.

From the decision to release 27 letters written by Prince Charles to seven British government departments, as sought by the Guardian newspaper under the Freedom of Information Act.

§§§

A veto to save the future King

Dominic Grieve

October 16, 2012

Within a constitutional monarchy, where the Sovereign is Head of State but political power is exercised through a democratically elected government, it is a vital feature of the constitutional settlement that the Sovereign cannot be seen to favour one political party above another, or to engage in political controversy. Without that preservation of political neutrality, the constitutional balance that allows for governments to be elected within the framework of inherited monarchy could not be preserved. Nor would it be possible for the Sovereign to fulfil his or her symbolic function as representative of the State.

In the United Kingdom, that constitutional balance is preserved by the constitutional convention that the Monarch acts on, and uses prerogative powers consistently with, Ministerial advice (“the cardinal convention”). The corollary to the cardinal convention is the convention that the Monarch has the right, and indeed the duty, to be consulted, to encourage, and to warn the government (the “tripartite convention”)…

In my view, it is of very considerable practical benefit to The Prince of Wales’ preparations for kingship that he should engage in correspondence and engage in dialogue with Ministers about matters falling within the business of their departments, because such correspondence and dialogue will assist him in fulfilling his duties under the tripartite convention as King. Discussing matters of policy with Ministers, and urging views upon them, falls within the ambit of “advising” or “warning” about the Government’s actions. It thus entails actions which would (if done by the Monarch) fall squarely within the tripartite convention.

If such correspondence is to take place at all, it must be under conditions of confidentiality. Without such confidentiality, both The Prince of Wales and Ministers will feel seriously inhibited from exchanging views candidly and frankly, and this would damage The Prince of Wales’ preparation for kingship… Moreover, it is highly important that he is not considered by the public to favour one political party or another. This risk will arise if, through these letters, The Prince of Wales was viewed by others as disagreeing with government policy. Any such perception would be seriously damaging to his role as future Monarch, because if he forfeits his position of political neutrality as heir to the Throne, he cannot easily recover it when he is King. Thus in this context, confidentiality serves and promotes important public interests…

Much of the correspondence does indeed reflect the Prince of Wales’s most deeply held personal views and beliefs… The letters in this case are in many cases particularly frank. They also contain remarks about public affairs which would in my view, if revealed, have had a material effect upon the willingness of the government to engage in correspondence with the Prince of Wales, and would potentially have undermined his position of political neutrality…

The Prince of Wales engaged in this correspondence with ministers with the expectation that it would be confidential. Disclosure of the correspondence could damage the Prince of Wales’s ability to perform his duties when he becomes king.

From the “Exercise of the Executive Override under Section 53 of the Freedom of Information Act 2000.”

Photo: ChameleonsEye / Shutterstock