The burly Soviet-era bank teller stares at me blankly and insists she cannot dispense funds unless I have a passport. Not identification, but my passport. Because it is a rule. I am coming from a press conference — not the airport; I don’t have my passport. If the bank machine were working, no problem — as much money as I want, no questions asked. But dealing with a breathing person, I need a passport. “I am not the machine,” she says. “I am the teller, and this is how we do things.”

My companion, a 30-year-old linguist (who has therefore lived the majority of his years in the post-Soviet era), shrugs his shoulders apologetically: “What can I say? Our Ukraine is a land of contradictions.” A land of contradictions, a country in transition — the new world colliding with remnants of the old. I do not get my money. We take the metro instead of a cab.

Another day, I get into a taxi. I give my address. The driver has never heard of the street. Three maps and two phone calls later, he figures it out: “Another name change. It used to be called Red Army Street — until last week, apparently.”

He explains this is an ongoing problem in Kyiv. Nineteen years after Communism, they are still in the process of replacing the old Soviet place names — and it’s driving the cabbies crazy.

A land in transition.

I am speaking with a young journalist at the Hay Loft Pub — a stylish and cozy basement establishment that tends to attract nationally conscious intellectuals. “Viktor Yanukovich will never make good on his campaign promise to make Russian a second official language. The people would revolt. It would be civil war. Everyone I know would be up in arms. With my generation, it would never, ever fly. A national insult,” he says.

Out of curiosity I ask him what language he speaks with his friends, outside of work. “Russian,” he replies. A land of contradictions.

Just off Independence Square, in a slim park (that is more of a boulevard median than anything else), stands a statue of Lenin — reportedly the last one remaining in Kyiv. Directly behind it, an enormous billboard advertises designer furs. A land of contradictions.

This is Ukraine in 2010: contradictions and transition. Culturally rich and beautiful in both architecture and landscape, this is a country with immense promise — geostrategically placed to be a European economic leader, significant regional military power and trade liaison between Western Europe and Russian and Asian markets. It is a country with immense but unrealized potential.

I visit the Bassarabian Market — a centuries-old farmers’ market famous for its roe, cured meats, pickled anything and cut flowers. An elderly woman peddling caviar laughs at me over some turn of phrase, saying my Ukrainian has pastoral streaks she hadn’t heard in 50 years. Despite her obviously modest income, she doesn’t care that possibly offending me could lose her a customer. She has had her fix of hilarity for the day! Half an hour later, I walk into the Chanel boutique on one of Kyiv’s main streets. Five attendants immediately spring to attention, exhibiting a discipline of customer service I have yet to see in Canada, let alone in Paris. A land in transition.

This is Ukraine in 2010: contradictions and transition. Culturally rich and beautiful in both architecture and landscape, this is a country with immense promise — geostrategically placed to be a European economic leader, significant regional military power and trade liaison between Western Europe and Russian and Asian markets. It is a country with immense but unrealized potential.

There are significant signs of change, but every manifestation of modernity is juxtaposed with its own glaring contrast.

I am in Kyiv for the runoff vote in the presidential election, part of the leadership team for the 200-strong Canadian observer mission. Our government-sponsored independent observer team — and the 16 other multilateral and bilateral observer teams from Europe, Asia and the Americas — are here to observe democracy.

As are all things in Ukraine, democracy here is complex and fraught with contradictions — and evolving. If we are here to find democracy, we certainly find it — but of a different kind than our home-grown variety. There is absolutely no doubt Ukraine is democratic. In fact, the political challenges here stem not from a lack of democracy, but perhaps an excess of it. Ukraine’s political system can fairly be described as hyperdemocracy or, as we joke in Kyiv, democracy on speed.

Ukraine’s incumbent president — Viktor Yushchenko — is obliterated in the first round of voting, gaining a mere 5 percent of the vote in his bid for reelection. According to Ukrainian electoral law, if no candidate wins more than 50 percent of the vote, the top two candidates proceed to a final runoff. In this election, the final contest for the presidency is between incumbent prime minister Yulia Tymoshenko and incumbent opposition leader Viktor Yanukovich.

Tymoshenko — or simply “Yulia,” as she is called here — is branded as the beautiful heroine of the prodemocracy “Orange Revolution” protests of 2004. She campaigns for integration with the European Union (EU), a crackdown on corruption and an acceleration of national rebirth policies, after half a century of RussoSoviet rule in western Ukraine and 300 years of Russian occupation in eastern Ukraine. She calls her opponent a sellout to Moscow, a puppet of Putin and the industrial oligarchs, and a cultural enemy of the Ukrainian people.

Yanukovich, in turn, brands himself as the champion of stability and prosperity. He campaigns on a “balanced” foreign policy — he will continue to press for EU membership, but in a manner that will not antagonize Russia. Prospective NATO membership is certainly off the table, and he is open to extending Russia’s lease on the naval base in Sevastopil, Crimea — home to Russia’s Black Sea fleet, perceived by many as a vestige of colonialism. Yanukovich also campaigns to make Russian a second official language — an accommodation for the large ethnic-Russian minority, and a recognition of the lingua franca of many ethnic-Ukrainians in the heavily Russified east. He calls Yulia an incompetent oligarch (she is worth about $300 million) who has sacrificed the economy and good governance to five years of political duelling with the outgoing president (her one-time ally), Viktor Yushchenko.

Not only is the field fiercely competitive, but the new government will have significant challenges to face. The financial crisis saw Ukraine’s economy shrink by 15 percent in 2009, and the parliamentary deadlock of recent years led the International Monetary Fund to suspend the last tranche of its $16.4-billion bailout package. Foreign investment and steel exports plummeted since the recession hit, and will require significant international economic growth before they can expect to recover.

An old-world European “pechatka” or “stamp” culture still plagues productivity. Lags and corruption surrounding business permits continue to be one of the greatest regulatory barriers to private sector development. One local laughed that his family had to obtain 600 separate stamps, seals and certifications to open a small enterprise.

Public debt has also increased dramatically during the recession, while hard currency reserves are dangerously low.

Moreover, frequent legal changes have resulted in a lack of stability that hardly inspires investment confidence among venture capitalists. These are but a sampling of the economic challenges to be confronted by the new administration.

The week leading up to the final February 7 vote sees immense tension. MPs from Yanukovich’s Party of Regions convene a special parliamentary sitting to amend the Law on Elections of the President of Ukraine. After a public showdown, the Regions parliamentarians succeed. Yes — they amend the electoral statute four days before the election.

The international community’s response varies from cautious silence (to preclude the perception of partiality) to mildly disapproving communiqués employing such diplomatic code as “international norms” and “accepted practice.” In a word, however, the international community is shocked. How can a “democratic” country amend its electoral law between balloting rounds, and a mere four days before the final vote?

As analysts, however, we must soberly consider the facts: Ukraine’s parliament is convened according to proper procedure and statutory notice. Amendments are introduced according to due process. They are passed by majority vote. The president signs them into law according to the Constitution. At which stage does the democratic process break down?

Differing perspectives on democratic norms pervade the system. Ukraine has no independent state agency akin to Elections Canada. The machinery of elections is governed at every level by committees of party representatives. Local polling stations are run not by neutral returning officers on contract with an impartial electoral body, but by committees of 16 volunteers — 8 appointed by each campaign — functioning on a principle of mutual scrutiny.

An instinctive Canadian response might be to dismiss this model as amateurish and unprofessional. Let us remember, however, the historical and political context of post-Communist Eastern Europe. A natural Ukrainian response to our professionalized system might engender equal surprise: “How can you trust the government to run a fair election? It is an inherent conflict of interest! Who appointed the senior central electoral officials? Who is lining their pockets?”

In Canada, governments are now reticent about proroguing Parliament without a sufficiently compelling narrative, despite their clear constitutional prerogatives. In Canada, the public erupts at the prospect of opposition parties building a coalition to replace a government weeks after it was elected. In Ukraine, politics is a blood sport.

The exit polls are released on election day upon the closing of polls. Yanukovich leads by 3 to 5 percent, depending on the poll. Yulia refuses to concede defeat, saying she will await the final vote count from official sources.

Two days later, the electoral commission echoes the exit polls with its preliminary vote count: Yanukovich has won by 3.5 percent. Yulia still refuses to concede. International observers generally commend the process as a genuine and free exercise, yet she does not concede defeat. She alleges widespread fraud, says she has the evidence to prove it and vows to appeal.

On February 14, the electoral commission reaffirms a Yanukovich victory, with a final vote count of 48.95 percent to 45.47. Voter turnout is 69 percent. Yulia still refuses to concede, and the following day launches an appeal with the High Administrative Court. Ukraine watchers and political analysts scratch their heads, wondering if the Prime Minister has lost her strategic sense. Nobody can follow her game plan.

Even on the day of Yanukovich’s inauguration, she maintains he stole the vote. The head of government of an emerging state refuses the one act that signals its democracy is truly mature: conceding defeat after a legitimate loss at the polls.

Yulia seems to understand instinctively she must do everything possible to weaken her victorious opponent, or else leave herself exposed. She knows Yanukovich will not allow her to retain her place as prime minister — despite leading the strongest coalition in Parliament. She knows that as soon as the dust settles, the pressures will begin to entice her parliamentarians across the floor with promises of station, influence or — most commonly, they say — money.

Politics here is dirty — and they play to win.

The more I reflect upon the system here, the more it becomes evident that the problems lie not in a lack of democracy — but in a lack of other balancing political influences.

Canada has had two and a half centuries — including colonial rule a century before Confederation — to build and hone a parliamentary system. We have come to revere not only democratic principle and practice, but other institutions as well: precedent, Parliament and its traditions, the courts and public-opinion-driven notions of best practice.

Ukraine has been holding elections for 19 years. Following red flags by international observers, the last two have generally been free and fair. They now get the democracy. What they still lack is the other pillars.

In most Western countries, public opinion would never permit amending the electoral law during a writ period. It would offend our sense of good practice and fair play. In Ukraine, anything goes as long as you have the numbers.

In Canada, governments are now reticent about proroguing Parliament without a sufficiently compelling narrative, despite their clear constitutional prerogatives. In Canada, the public erupts at the prospect of opposition parties building a coalition to replace a government weeks after it was elected.

In Ukraine, politics is a blood sport. Anything goes, provided the Constitution has granted you the power. Coalitions are ever-shifting, with prime ministers coming and going between elections. At one point it was whispered that the going rate for crossing the floor was US$1 million. All that matters is getting the numbers and delivering the votes. Fair play and ethics fall victim to the supreme reality of brute force democracy.

Elections in Ukraine are like nomination races in Canada. While it is increasingly rare now in our system to see such manoeuvres as last-minute membership sign-ups, strategically rescheduled nomination meetings or hostile takeovers of riding associations, they still do happen at our entry-level stage of political engagement. In Ukraine, this anything-goes/must-win culture dominates politics at the highest levels.

Will anything change? Will Ukraine eventually evolve into a more stable democracy that values ideals beyond mere victory? Fortunately, positive signs are emerging. The people clearly want their political culture to take the next step, and eventually it will also be in the interests of the political elites for this to occur.

On election day, international observer missions throughout the country marvel at the pride they see among polling station executives. Far from the fears of late legal amendments leading to mass confusion and rule manipulation, local electoral commissions work harmoniously in a conscious effort to demonstrate their democratic bona fides. Polling stations open on time, in accordance with the law. Ballots and ballot boxes are publicly certified before observers and scrutineers. Electoral commissions troubleshoot where the law is silent, and make decisions guided by a combination of democratic vote and common sense. They take pride in their roles and duties, clearly eager to demonstrate that the “irregularities” of past elections are truly a thing of the past.

The political parties themselves look like their modern, Western counterparts. With the press conferences or rallies dominated by 20and 30-somethings in suits they can hardly afford and packing at least one cellphone each, it is difficult to distinguish such events in Kyiv from a staff caucus in Ottawa. Party members take themselves and their roles seriously, and they are engaged because they believe in their country and its future.

The press is pluralistic and free — almost too free. As one local politico explains to me, a critical difference between Ukraine and Russia is that the Russian media self-censors. It is constitutionally free and enjoys the trappings of legal protection, but every journalist knows exactly what the state will tolerate in their reporting. The result is an anemic press that turns a blind eye to government excess, and can often be mistaken for a propaganda arm of government. In Ukraine, she explains, the media is so pluralistic and free now that the most common complaint is the multiplicity of choice of what to watch and read. There are few shared media experiences, and one’s sense of the national news agenda is entirely different depending on the media one consumes. Moreover, wherever an agenda exists, it is not that of the government.

Whatever one may say about the Orange Revolution’s infighting, one of its lasting legacies is a free press. In fact, one catalyst of the Orange Revolution was the cover-up surrounding the 2000 assassination of Georgiy Gongadze — a high-profile journalist who founded Ukrainian Truth, a news Web site that freely took shots at then President Kuchma, his oligarch backers and their collective control of the mainstream press. Following the national humiliation of the Gongadze affair, vented by Yushchenko and Tymoshenko, a free press is here to stay.

Even the power of the oligarchs is predicted to be on the verge of stabilizing. Immediately after independence, Ukraine endured years of gangster capitalism, complete with political insiders seizing assets through rigged privatization schemes. In many cases, the Communist Party apparatchiks of yesterday became the billionaire captains of industry of today. Ill-begotten as their wealth and status may be, those same powers are now starting to demand a strong rule-of-law system to protect their economic interests.

The self-interest of the oligarchs may even be a hidden weapon against the perceived threat of renewed Russian imperialism. Many voters feared Yanukovich’s campaign of closer ties with Russia as a harbinger of death for Ukrainian economic — and ultimately political — sovereignty. Others, however, argue that Ukraine’s oligarchs are in fact more powerful than their Russian counterparts, and that while Ukraine’s billionaire class may be primarily russophone, it has very little interest in political arrangements that could weaken its economic grip. Customs unions and financial and regulatory harmonization with the elephant to the northeast could do just that.

The ballot choices also signal a change in the air. The fourth finisher in the first round of voting — Arseniy Yatseniuk — hails from the next generation of leaders. A lawyer, former National Bank chairman, parliamentary speaker and foreign minister, he is still in his mid-30s. Despite his fourth-place finish, he came in far more strongly than expected. Regardless of how he would have performed as president, his strong showing signals an increasing willingness to opt for new leaders with little baggage and association with the past Ukrainians want to leave behind.

Perhaps the strongest sign of impatience is the strong placement of another contender — the faceless option on the final ballot. In this nail-biter election where every vote counts, 4 percent chose to cast their ballot not for their prime minister, not for their opposition leader, but for the third option — “Against All.”

During my final taxi ride from downtown Kyiv to Borispil International Airport, I discuss the election with my young driver. He is blasé about the initial results. He proudly voted Against All, and explains his rationale with the defiance of a poet as we cross the wide Dnipro River: “Do you see those waterfront houses over there? Right now they are all owned by the corrupt nouveaux riches. They seized their money from our country, and now they drive expensive sports cars to their trendy clubs while seniors can barely afford to live on state pensions. The gang in power has no class and no compassion. And they run everything. My generation will take over soon, and when it does, everyone will have a fair shake.”

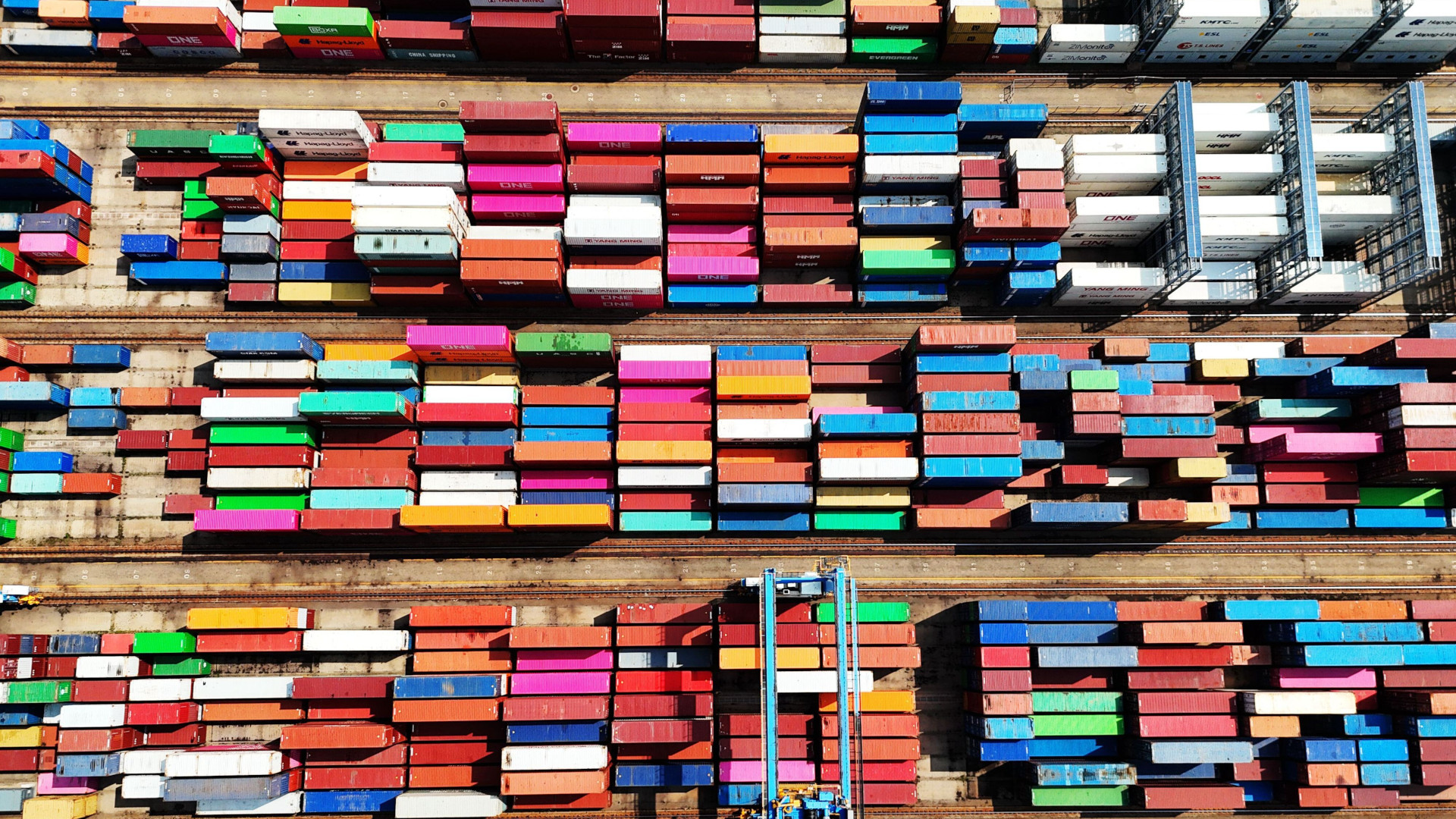

Photo: Shutterstock