(Version française disponible ici)

The causes of the low productivity of Canadian companies are well known and documented: they invest little, spend less on research and development than those in other rich countries, and have a low propensity to innovate. These behaviours tend to limit their productivity gains and, consequently, restrict the growth of the Canadian economy.

It is difficult to understand why our companies are reluctant to engage in activities that are central to success in comparable countries, or why the federal government continues to let it happen when the result is that the Canadian economy has fallen behind.

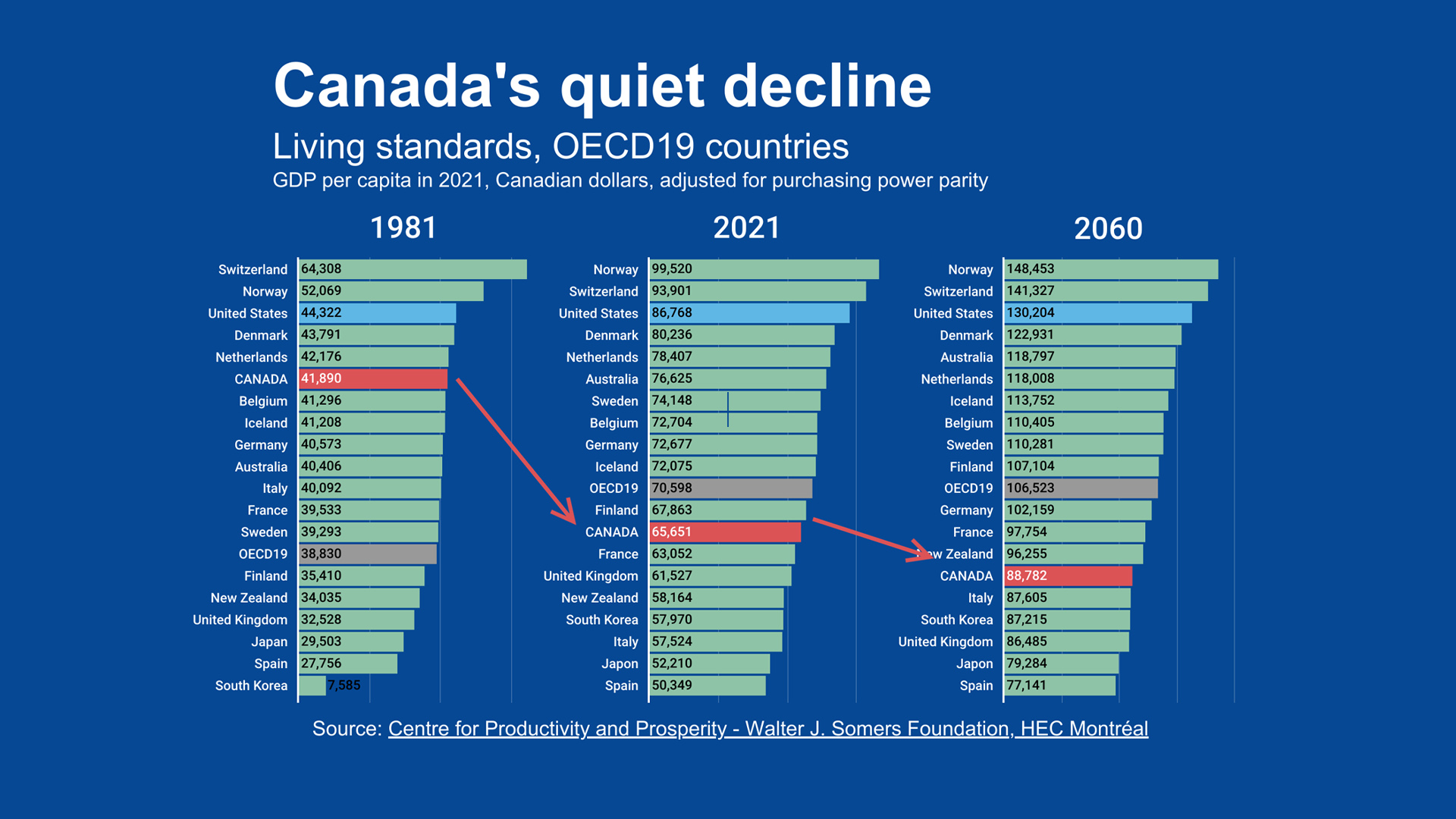

There is an urgent need to act because the consequences of inaction are enormous. In 1981, Canadians enjoyed a $3,000 higher per capita standard of living than the major Western economies (adjusted for inflation and currency fluctuations). Forty years later, Canada was $5,000 below that same average. If the trajectory continues, the gap will be nearly $18,000 by 2060. Canada’s Department of Finance has also reported these alarming projections.

Dear Canadians, please compete among yourselves

In examining why Canadian businesses are so reluctant to invest and innovate, the Centre for Productivity and Prosperity – Walter J. Somers Foundation (CPP) concluded that the problem is a lack of internal competition. Competition among Canadian companies is too weak and simply does not generate the incentives that would normally boost their competitiveness.

The federal public service strike could set patterns for workers across Canada

Canadian firms operate in small, highly dispersed markets that are very segmented economically and legislatively. They therefore compete much less with each other than American or European firms, which operate in two large, highly unified and integrated domestic markets that provide an adequate level of competitive pressure. This is not the case here: Canadian companies do not need to invest and innovate as much to stand out and maintain their market share. As a result, they are not competitive enough to compete in foreign markets. Growth suffers and the country’s economy stalls.

What makes this problem particularly embarrassing is that the Macdonald Commission clearly identified it in the early 1980s. It even proposed viable solutions – many of which are still applicable.

A free trade agreement, and then… nothing

Unfortunately, our policymakers chose only one solution: a free trade agreement with the United States. Once that agreement was in place, interest in the other options quickly faded and the government of Canada failed to move forward with the required reforms. The consequences of this inaction have been particularly damaging to Canada’s competitiveness and its ability to make the economy grow.

While Canadian exports benefited greatly from the free trade agreement with the United States in the 1990s, this “success” was largely due to the depreciation of the Canadian dollar rather than to the quality and quantity of Canadian investment and innovation. And in the early 2000s, when the Canadian currency began to appreciate against the U.S. dollar, companies from emerging economies quickly outperformed Canadian ones. Our country, inadequately prepared for competition, began its downward spiral, unable to take advantage of global market integration.

Canada now remains stuck in an interventionist logic dedicated to protecting the immediate interests of Canadian companies. Successive governments have failed to move on from protectionist reflexes and impose the necessary reforms: they should have adjusted the regulatory framework to stimulate the competitiveness of Canadian companies in the domestic market. Instead, Canadian companies continue to operate within an outdated institutional framework that does not value competitive forces.

An OECD index, which assesses the impact of government policies on competition, shows how outdated Canada’s regulatory framework is: Canadian government intervention in economic activity causes more distortion than elsewhere in the West. In addition, barriers to entry in Canada are more numerous and significantly more constraining, and the overall regulatory framework is more restrictive. In other words, Canada will have to work twice as hard to make up for lost time and establish a true competitive culture.

To reverse this downward spiral, the federal government should put competition back at the heart of Canada’s economic strategy. The priority should be to tackle whatever is holding back the development of a strong and resilient domestic market. There are too many regulatory barriers to interprovincial trade. When making decisions on competition, Canada should prioritize the interests of consumers rather than the interests of business.

No matter how many trade agreements our governments make, growth will remain inadequate and our standard of living will continue to quietly decline unless we put competition back at the heart of Canada’s economic strategy.

For more details, see: Productivité et prospérité au Québec – Bilan 2022 by Jonathan Deslauriers, Robert Gagné et Jonathan Paré, Centre sur la productivité et la prospérité – Fondation Walter J. Somers, HEC Montréal, Mars 2023

Also from Jonathan Deslauriers and Robert Gagné:

We lack workers. Quebec must stop trying to create jobs