Canada lags behind most other OECD countries when it comes to public reimbursement of prescription drugs and medicines. That’s partly because most other leading industrialized countries approach public drug plans differently than Canada, resulting in far broader access for their residents.

We have found this to be the case in each of our annual surveys of OECD countries over the last three years. The latest report, published in November 2009, compares public reimbursement of pharmaceuticals in OECD countries. This year’s version expands the number of countries to 25 and compares access to the 103 drugs reviewed by the Canadian Expert Drug Advisory Committee (CEDAC), a component of the Common Drug Review (CDR), since the CDR’s inception in December 2003 to the end of 2008. Public drug plan reimbursement measurements were taken in July 2009. For the third year in a row, the report demonstrates that Canada lags behind other OECD countries.

Pharmaceuticals are not part of the medicare system when dispensed outside the hospital in Canada. Provincial public drug plans were developed to close part of this gap so that patients could have access to medicines that are now a key component of the health care system. The results of the report beg the question of whether Canadians are getting appropriate access to medicines through our public drug plans. It should also be food for thought for public drug plan managers, who must make difficult choices within their allotted budgets, and for the tens of thousands who run into health problems only to discover they have to make do with something other than the latest in treatments.

Over the last quarter century, pharmaceuticals coupled with advances in medical knowledge have contributed to incredible improvements in virtually every field of medicine. Studies by the Canadian Cancer Society indicate that 80 percent of children with leukemia are still alive five years after diagnosis, while in the early 1970s, only a minority of children survived leukemia. This improvement in survival represents important advances in drug discovery coupled with improvements in overall care of cancer patients.

AIDS patients have also benefited. The first case of AIDS in Canada was reported in 1982. Following a steady rise of HIV/AIDS-related deaths until 1995, the introduction of innovative pharmaceuticals has had a dramatic effect on reducing deaths — by 66 percent for males and 43 percent for females, according to the Public Health Agency of Canada. The new HIV/AIDS treatments have also improved the quality of life of patients, by decreasing the pill burden and reducing side-effects. Medical research leading to better prevention, diagnosis and treatment has also resulted in a dramatic decline in the cardiovascular disease death rate in Canada over the past 50 years. According to Health Canada’s Cardiovascular Disease Surveillance On-Line, between 1969 and 1999, mortality rates for all cardiovascular diseases decreased by 56 percent. This improvement happened not all at once, but through continuous innovations in lifestyle (diet and exercise), surgical techniques and medicines.

Innovative medicines are proven cost savers as they help patients live longer, more productive lives; reduce costs related to employee absenteeism and disability; and lessen demand on other, more expensive areas of the health care system, such as hospital stays and surgeries. Yet public drug plan managers usually have to deal with a stand-alone budget. Adding a new drug may benefit the health care system, but the drug plan manager may have difficulty in finding the funding in his or her budget. Our report asks whether this approach gives Canadians good value for tax dollars.

Canada spends about 10 percent of its GDP on health, ranking 6th out of 21 OECD countries. Governments in Canada consistently pay about 70 percent of the total health care costs. The 2007 figures rank Canada 19th out of 24 OECD countries.

Canada spends 17.7 percent of its total health expenditure on pharmaceuticals, including drug costs — prescription and non-prescription, distribution, and professional fees and allowances. This ranks Canada 7th out of 21 countries (data are not available for all countries), which is close to the average of 15.4 percent in this category, grouped with countries such as Italy, France and Belgium.

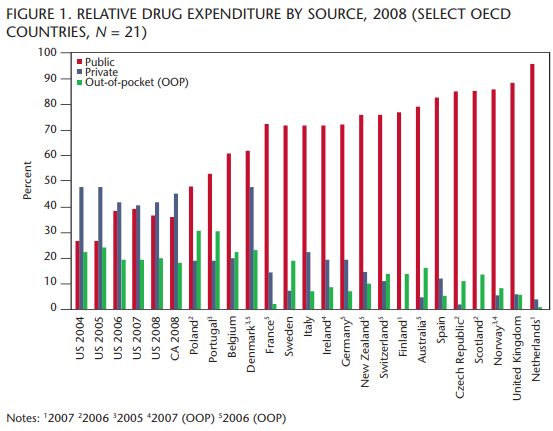

Canada and the United States are in a virtual tie for last place compared to the other countries on public spending on pharmaceuticals, at 37.5 percent (figure 1), which is about half the average (70.9 percent) of the other countries studied.

Pharmaceuticals are not part of the medicare system when dispensed outside the hospital in Canada. Provincial public drug plans were developed to close part of this gap so that patients could have access to medicines that are now a key component of the health care system.

These figures demonstrate that governments in other countries pay a much larger share of the overall costs of pharmaceuticals as an integrated part of health delivery. Canadians are fortunate to have a strong private drug plan sector in Canada, but this may be somewhat at risk because of the economic slowdown.

Sometimes we hear that drug costs are rising too quickly or are too high. In Canada they have risen from 8.5 percent of total health expenditure in 1978 to 17.7 percent in 2007 — in effect doubling as a percentage of health care spending over the last 30 years. It is important to note that the reporting methodology includes costs related to generic and patented prescription drugs, over-the-counter drugs, allowances and fees, and personal care products. Looking at absolute growth in drug costs without context paints a misleading picture because the increasing use of pharmaceuticals is due to many legitimate factors, including the value of medicines for improved patient outcomes.

However, while a drug may prevent a hospitalization, the reality for governments is that someone is always there to fill that hospital bed. There never seem to be enough beds even though many hospitals run deficits. The reality is that pharmaceuticals play a valuable role in the overall delivery of health. Without new and innovative pharmaceuticals, the hospital situation would be much worse.

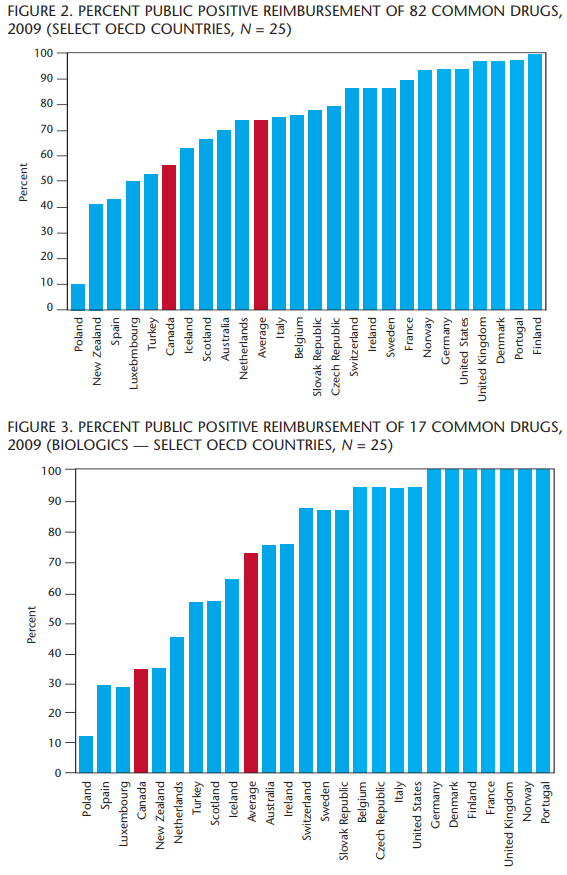

We have seen that Canada ranks above average when it comes to percent of GDP spent on health, but the contribution made by governments is below average. Canada also ranks above average when it comes to the percentage of health care dollars used for pharmaceuticals. And Canadian governments rank last out of 21 countries studied in the public portion of pharmaceutical spending. Is it possible that Canada’s system leads to the under-funding of pharmaceuticals by governments? The report focused on the drugs that are common to at least 15 of the 25 countries studied. This means that the list of drugs was reduced from 103 to 82. Figure 2 shows the percentage of those 82 drugs that is reimbursed by public drug plans in each of the countries. “Percent Public Positive Reimbursement” counts a drug as reimbursed if it is reimbursed in any way, shape or form, even in the most limited way.

Over 90 percent of the drugs were reimbursed in seven countries. On average, 74 percent of the drugs studied are reimbursed by public drug plans in the countries studied. CEDAC recommended that only 56 percent of the drugs be reimbursed. Canada ranks 20th out of the 25 countries studied. This is well below the average and comparable to the standing of Iceland and Turkey. The average falls to 52 percent when we consider the actual reimbursement by Canadian public drug plans.

In figure 2, Canada is represented by the CDR recommendations. CDR has recommended “Do Not List” for 36 drugs, which is the highest number among all countries.

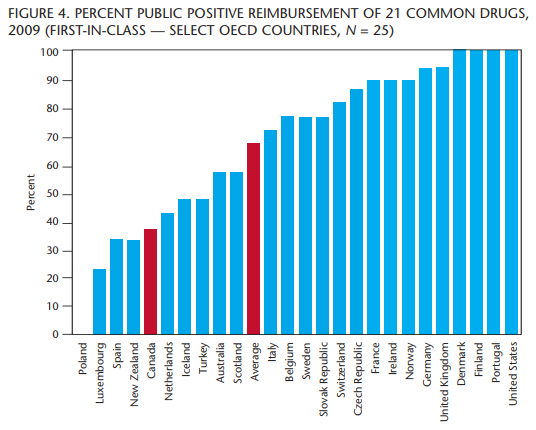

A “biologic drug” is defined as a substance that is made from a living organism or its products and is used in the prevention, diagnosis and/or treatment of cancer and other diseases. The introduction of biologic drugs over the past 10 years has been challenging for those charged with making reimbursement decisions. Of the 103 drugs reviewed by CEDAC since 2003, 20 are biologics. One of those drugs was withdrawn from the market and two are not available in many countries, leaving 17 drugs to be analyzed.

Figure 3 shows that Canada and New Zealand are tied for 21st place, reimbursing only 35 percent of the biologic drugs in this study. This means that 80 percent of the countries studied allow some form of public reimbursement for more new, innovative biologic drugs than either CEDAC recommends or PHARMAC (Pharmaceutical Management Agency of New Zealand) reimburses. This is well below the average of 75 percent. No fewer than seven countries reimburse 100 percent of the biologic drugs.

These drugs are often used for conditions that are difficult to treat or may indeed be life-threatening. Are Canadian lives at risk because of the way these drugs are being assessed?

When we hear the word “innovation,” terms like “first” come to mind. Many publications speak of “First-in-Class” drugs but there is no agreed-upon definition for what constitutes a “First-in-Class” drug. Still, we want to know how Canada ranks when it comes to fostering innovation.

For the purposes of this study, a “First-in-Class” drug is defined as having one or more of the following characteristics:

- Represents a new chemical entity in a new class of drugs

- First drug for a specific disease where no other effective treatment is available

- First drug type to be taken in a new format (e.g., oral vs. intravenous)

- An innovative drug that the medical community generally believes to represent a medical breakthrough

Combination drugs of already existing products are not considered to be “First-in-Class” drugs, and it should be noted that “First-in-Class” does not necessarily confer “Best-in-Class” status on a drug.

Based on this definition, 24 of the 103 drugs in the study were considered “First-in-Class.” Of the 24 drugs, 21 were common to all countries studied. Once again, in figure 4, Canada ranks near the bottom of the list, ranking 21st out of the 25 countries studied for reimbursement of these drugs.

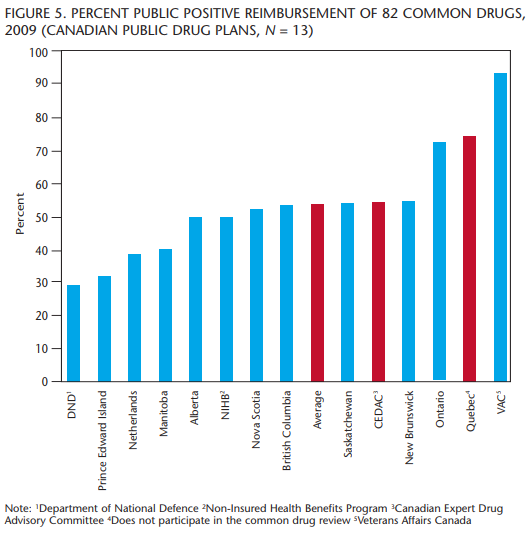

Figure 5 provides a snapshot of what percentage of drugs the different public drug plans in Canada reimburse and illustrates the large range that exists within Canada.

The plan for Veterans Affairs Canada (VAC) reimburses most drugs, usually on a case-by-case basis. This means a drug may be reimbursed, or not, based on whether the patient’s physician can convince the drug plan that the drug is necessary. Quebec does not participate in the CDR and reimburses more drugs than any other province in Canada. Quebec also has developed government policy about pharmaceuticals. Quebec wants to provide good treatments for its residents and also wants a viable pharmaceutical sector operating in the province. For Quebec, it is not only about cost, it is about investment in health and in jobs.

Ontario passed the Transparent Drug System for Patients Act in 2006, and we are starting to see differences in how drugs are reimbursed in Ontario. It is adding more drugs to the reimbursement lists than other provinces that participate in the CDR. Ontario has the most unrestricted listings (24), but the province also has the second-highest number of drugs reimbursed on a case-by-case basis.

Most provinces reimburse around the average number of drugs, which is also close to the percentage recommended by the CDR. PEI and the Department of National Defence (DND) reimburse fewer drugs than other public plans.

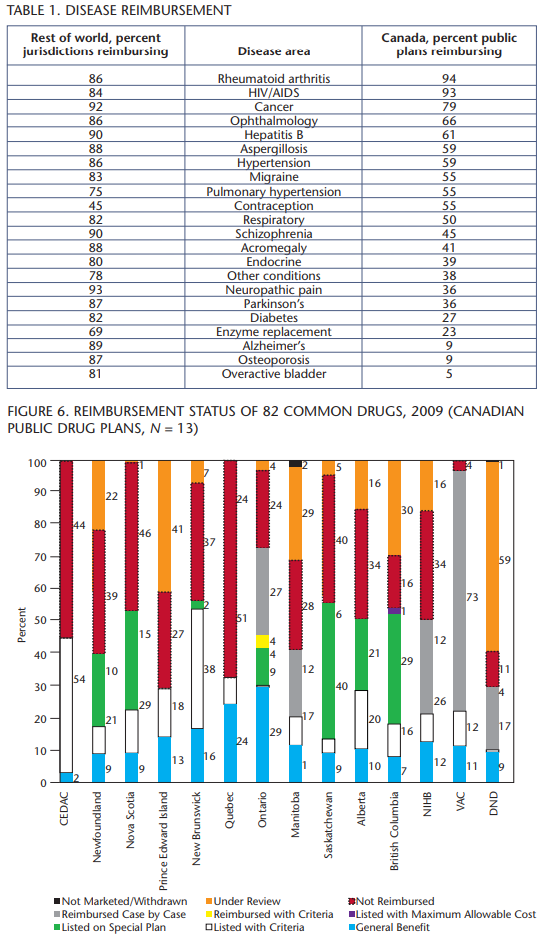

Figure 5 shows public drug plan reimbursement in Canada generally. Figure 6 shows how the public plans in Canada actually reimburse the 82 drugs in the study. Quebec provides the most actual listings. Veterans Affairs and Ontario reimburse many drugs through their respective case-by-case mechanisms, which is by no means certain. Anecdotal reports indicate that case-by-case reimbursement for some of the drugs is not impossible, but is very difficult to obtain. This begs the question: Is there a threshold by which we should categorize a drug as truly reimbursed? If yes, what should it be?

Recommendations from CDR have an impact on the public drug plans in Canada. CEDAC “Yes” recommendations are applied differently by public drug plans based on several factors, including plan objectives. This leads to significant variation in the relative ease of reimbursement, from “General Benefit” with no conditions, to “Listen with Criteria,” to “Reimbursed Case by Case,” to “Not Reimbursed.” This means a drug may or may not be reimbursed even with a positive CEDAC recommendation, essentially a “Maybe.”

When CDR recommends “Do Not List,” the public drug plans are continuing to interpret this recommendation as “Do Not Reimburse” at all. Does this mean that appropriate therapy is denied? This point was raised in last year’s report and we have not seen any progress on this issue.

These findings raise the concern that patients may not be getting the therapy they need because the system is designed to recommend a drug only if (1) it suits the majority of the population and (2) it is deemed “cost-effective.” The system, in most cases, does not allow for individualization of therapy. Is this consistent with best medical practice? We have to find a better solution. People are being left behind.

The 82 drugs in the study represent a wide number of drug categories. Comparing the reimbursement of drugs categories among the 11 major Canadian public drug plans and the remaining 24 countries yielded some interesting information (table 1). The numbers for the individual disease states are small, but there seem to be significant differences in how disease categories are treated. For example, diabetes is becoming a burgeoning problem in Canada. There is a national strategy to combat diabetes, yet newer medications for diabetes are not being reimbursed very well. How is offering fewer options for drug therapy helping the national strategy? More investigation is planned in future studies.

Governments in Canada pay a smaller share of spending in both overall health care and pharmaceuticals than governments in other OECD nations. Overall spending on pharmaceuticals is not out of line with that found in other developed countries, but governments in Canada rank last among the countries studied in the public contribution toward pharmaceuticals.

CDR does have an impact on public drug plan decisions. We still see that “Yes” pretty much means “Maybe” and “No” pretty much means “No.” As noted, public drug plans in Canada are often not reimbursing at all when CDR says “Do Not List.” We believe that this needs to change because medicines that are not being reimbursed may be appropriate for a number of patients.

The Common Drug Review has continued to update its processes since its inception in 2003. Data from Wyatt Health Management’s CDR Tracker® also show that CDR completes its reviews in a timely manner. The CEDAC recommendations are a function not of how well CDR does its job, but how recommendations are delivered. Currently, CEDAC recommendations are worded as “List,” “List in a Similar Manner,” “List with Criteria” or “Do Not List.” It is our opinion that the wording of these recommendations limits the usefulness of the CDR because of the way they are interpreted by public drug plans, especially “Do Not List.”

In the past, “Do Not List” usually meant that the drug was not listed on the formulary, but special authorization mechanisms allowed for the drug to be reimbursed on a case-by-case basis. As noted earlier, that type of reimbursement is still available. However, now “Do Not List” is often interpreted as “Do Not Reimburse” in any way. As the CDR states on its own website: “The CDR was set up to reduce duplication, and provide equal access to high level evidence and expert advice, thereby contributing to the quality and sustainability of Canadian public drug plans.”

It is possible that much of the work that CDR does goes down the drain when a “Do Not List” recommendation is issued because the public drug plans usually decide to not reimburse. A re-submission to CDR is necessary to change the recommendation. This can add a year or more to the reimbursement process. We recommend a different approach. It is our opinion that the CEDAC recommendations should focus not on a “Listing” but on the “Place in Therapy” for the drug under review.

In essence, this is what CEDAC does anyway when it recommends that a drug be “Listed with Criteria.” “List with Criteria” is the predominant positive CEDAC recommendation, making up nearly 69 percent of all positive CEDAC recommendations.

There are a number of benefits to following this approach:

- Payers often see some value in the new drug, but when the drug does not pass the “Listing Threshold,” payers are in a quandary as to how to reimburse the product. Determining “Place in Therapy” has the potential to provide more overall value for drug plans because that type of recommendation reduces the need for additional clinical review that takes place in a number of provinces.

- The well-established CDR process does not have to change significantly.

- “List with Criteria” (“Place in Therapy”) is already well understood by stakeholders

- “Listing” or, more correctly, “funding” is still decided by the public payers.

- Reimbursement criteria can still change over time with the development of new evidence.

Our report only scratches the surface. A more inclusive national dialogue on pharmaceutical care is necessary to find real solutions.

New drug therapies may continue to increase drug costs. However, new drug therapies may not drive up overall treatment costs. Just because a new drug is not reimbursed does not mean that the patient goes away unless he or she dies. Patients who are not doing well on current therapy will usually look for substitutes, such as other pharmaceuticals or health services, including hospitalization. Those substitutes may be ineffective (wasting resources) or far more costly than the therapy under consideration for that patient. It is important to see new medicines, not solely as a segregated cost but as an investment in better, more cost effective health care. Governments may state that is what they are doing now, but the study results speak differently.

New medicines and vaccines are part of the solution by improving patient outcomes and helping to make our health care system sustainable by reducing costs elsewhere in the health care system.

Isn’t it better to look for more ways to provide appropriate therapy? What is the real cost of not providing appropriate therapy? We need to find better ways to say “yes” to people who really need the right therapy.

Photo: Shutterstock