It only took a few minutes. I stepped out of the makeshift war room in our election-night operations at the Intercontinental Hotel in downtown Toronto to make a few short calls to congratulate newly elected New Democratic Party (NDP) Members of Parliament from Atlantic Canada.

By the time I returned from the adjoining room, the team had taped a bunch of flip-chart paper to the walls with the names of dozens and dozens of Quebec ridings scribbled on them. We knew what the opinion polls showed and what it felt like from street level, but with no ground game in the province, we just didn’t know if the flood of seats we knew was possible would actually materialize.

Just to be sure, I asked if the names on the wall represented ridings under legal disputes. “No. These are the ridings we’ve won — so far,” a colleague said. “Holy shit,” I said. “This thing is real.”

It was the beginning of a long and historic night, with breakthroughs from St. John’s to Newton, BC.

In the GTA, the Greater Toronto Area, we had broken through with new seats in both the west and east ends, for a total of nine Toronto-area seats — our best ever in Canada’s largest city.

And in Quebec, we had broken through with over 40 percent of the vote and 59 seats. We won the former seats of Sir Wilfrid Laurier, Louis St-Laurent, Brian Mulroney, Jean Chrétien and Paul Martin. We beat Bloc Québécois leader

Gilles Duceppe in Laurier-St. Marie by 5,400 votes.

It was an outcome that very few outside Jack Layton’s circle believed was possible and one that even fewer predicted.

So how did it happen? Was it an accident? Was Jack Layton — and the 2011 NDP campaign — simply the benefactor of lacklustre performances from the Liberals and the Bloc Québécois? Or was it something more?

To understand how the “Orange Crush” on May 2, 2011, came to be, you have to go back to the beginning —to the dining room table at Jack and his wife Olivia’s Toronto home in the spring of 2002.

That’s where a group would meet to map out the game plan to win the NDP leadership, professionalize the operations of the party and expand its support to create a viable alternative to form government. The effort would affectionately become known as “the project” by those of us around the table.

Jack would often quote Tommy Douglas, “dream no little dreams.” Considering the state of the party 10 years ago, the project was, indeed, no little dream.

In the spring of 2002, the NDP was the fourth party in the House of Commons. In its most recent election, the party had won 13 seats with 8.5 percent of the vote, about half of the NDP’s historical average.

The years leading up to these disappointing results were even bleaker. In the 1993 election, the party under the leadership of Audrey McLaughlin received 6 percent of the vote and nine seats. The NDP lost party status in the House of Commons.

And when Alexa McDonough, who replaced McLaughlin in 1995, formally announced her resignation as leader on June 4, 2002, the ground didn’t feel much more fertile for New Democrats, with a caucus of only 14.

The party faced significant organizational and financial challenges. The cramped federal office on Albert Street had a dedicated, but small team, and with annual revenue of less than $3 million, the federal party was reliant on the better-resourced and better-organized provincial sections of the party to undertake its federal campaigning.

And in Quebec, we had broken through with over 40 percent of the vote and 59 seats. We won the former seats of Sir Wilfrid Laurier, Louis St-Laurent, Brian Mulroney, Jean Chrétien and Paul Martin. We beat Bloc Québécois leader Gilles Duceppe in Laurier-St. Marie by 5,400 votes.

Within the grassroots of the party, there was a full-blown existential crisis underway. At the policy convention in the fall of 2001, 40 percent of the delegates voted to disband the party in favour of an ill-defined, far left-wing party.

The bottom line? By 2002, the party was in deep trouble. The leadership race to replace Alexa was a make-or-break opportunity to get the party on a fundamentally different path.

Jack Layton, the media-savvy city councillor from Toronto, personified what the party needed at the time. He was urban, bilingual and experienced in both elections and governance as a long-standing elected member of Canada’s largest municipal government.

Layton’s leadership campaign offered a simple and concise message: more members, more votes and more seats would mean more clout in Parliament to build the Canada we want. Being the conscience of the nation and hoping other parties in power would adopt our policies wasn’t good enough. Jack wanted the levers of power.

It was an optimistic and hopeful campaign, which included making the case to build in Quebec. Jack would say we couldn’t call ourselves a truly national party if Quebec wasn’t a part of it. The campaign played to the aspirations of New Democrats, of what we could be.

With a one-member-one-vote leadership contest, the strategy to win was simple: sell a lot of memberships before the cut-off. For that, we turned to the talented network of people with whom Jack and Olivia worked in Toronto.

Beyond their home base, we tapped his numerous contacts from his time as president of the Federation of Canadian Municipalities, as well as former activists from the student and environmental movements. These organizers were talented and knew how to win, but many getting involved in the federal NDP for the first time.

With this superior organizational clout, Jack was elected party leader on the first ballot on January 25, 2003. Step one of the project was complete.

Jack was now leader of a broke party, dead last in the polls and written off by the Parliamentary Press Gallery. We knew that the rest of the project would not come about overnight. If we were to be successful, we would have to work hard, learn from our past mistakes and never lose focus.

We would have to play the long game.

In addition to internal obstacles, we were facing significant external challenges heading into the 2004 campaign. By then, I had moved from Toronto to serve as director of communications for the NDP.

Paul Martin had just been crowned as the leader of the Liberal Party in November 2003. Some commentators looked at his organizational and financial strength and his personal popularity, and mused openly that he would wipe the NDP and its new leader right off the map.

Then, in December 2003, the Canadian Alliance and the Progressive Conservative Party voted to merge, ending the split in the small-c conservative vote and bringing together greater organizational and financial capacities.

A month later, a new law came into effect that essentially banned all corporate and union financing of political parties. Since 1961, we had counted on labour for about a quarter of our campaign financing and we relied on unions to guarantee our campaign loans. As of January 1, 2004, this was no more, and in the lead-up to the June campaign we were still retooling our fundraising efforts.

Despite these challenges, we focused on the immediate task at hand: raise Jack’s profile and get the NDP in the game. Jack toured tirelessly, including in Quebec. Our media and communications strategies were sharper and punchier.

Our goal was to get the party to 20 percent in popular support by the time the election was called. We hit our target one month before the election in a May Compas poll. We were heading into the campaign with twice the support we had in 2000.

Encouraging poll numbers suggested that we could win in ridings all over the country. We spread our limited resources and our hopes accordingly.

On June 28, 2004, the NDP received 2.1 million votes and nearly doubled its overall share of the national vote with 16 percent. However, despite this strong growth in votes, the party gained only 5 seats for a total of 19. Olivia lost her battle against a Liberal incumbent in Toronto.

We learned a lot from that campaign.

In addition to spreading too thinly our limited ground resources, our platform was too unfocused and too costly. We had eight commitments and each had subpoints. Jack would later admit he couldn’t remember the points off the top of his head. The campaign, run by committee, was focused more on satisfying internal interests than appealing to voters.

And our lack of preparation for the last-minute appeal by the Liberal Party, calling on all non-Conservative voters, especially New Democrats, to vote Liberal, proved to be brutal.

Paul Martin stood in a parking lot rally in my hometown of Coquitlam, BC, and told people that by voting NDP, you’d be helping to elect the Conservatives. This was not only desperate, but also untrue in many ridings, especially in western Canada, where it was a two-way fight between us and the Conservatives.

But enough voters listened to Martin. And in ridings where the NDP was either leading or in second place behind a Conservative, people abandoned the NDP and voted for the third-place Liberal candidate, ensuring more Conservatives got elected.

This was the latest incarnation of something that had confounded the NDP since before its founding: appeals to get NDP supporters to vote Liberal in an effort to stop Conservatives improperly labelled as “strategic voting.”

Layton’s leadership campaign offered a simple and concise message: more members, more votes, and more seats would mean more clout in Parliament to build the Canada we want. Being the conscience of the nation and hoping other parties in power would adopt our policies wasn’t good enough. Jack wanted the levers of power.

Around 3:00 a.m. on election night, long after the speeches were done, I remember watching the final results coming in from very tight races in BC. During the evening, we had as many as 26 seats in which we had won or were leading. Every few minutes, another NDP seat would move over to the Conservative column. I thought if I shut the TV off maybe our slide would stop. It did — at 19.

Winning only 19 seats was devastating. Despite some rookie miscues, we thought we had a run a big-league campaign. The results were a hard kick to the groin. And it was exactly what we needed. We made a lot of mistakes and we committed to learn from each of them.

But as we debriefed from the 2004 campaign, we also identified three reasons to be optimistic for the next one. In addition to increasing our vote count by a million, we came in second in 51 ridings. We also lost 10 seats by fewer than 1,000 votes, giving us target areas for growth in the next campaign.

We also had an immediate opportunity. For the first time since 1979, Canada had a minority Parliament. And while we did not have a clear balance of power, we did have an opportunity to steer the direction of Parliament.

If we initiated positive results in Parliament, our MPs would not only be fulfilling their duties as parliamentarians, but we would have something in the next campaign that very few opposition parties ever have — a track record of accomplishments.

When Parliament fell on November 28, 2005, kick-starting a 55-day campaign, we had already made significant strides in branding the NDP as the party that gets results for families. Jack’s experience at City Hall, where adversaries strike deals to get things done, proved vital to accomplish this task.

But Jack not only redirected $4.6 billion in corporate tax cuts in the 2005 budget to invest in transit, social housing, post-secondary education, the environment and foreign aid, the strategic move (dubbed by the media as the first-ever “NDP budget”) also set up a nice contrast between the priorities of the NDP and the Liberals.

And we were ready. Martin and his team, taking a beating over the Gomery Commission’s probe of the sponsorship scandal, had already promised an election in early 2006, so our team was in place.

Brian Topp, who was the director of the war room in the 2004 campaign, was appointed campaign director and Sue Milling as deputy director. Virtually all of the players were in place again and this would be our second federal campaign together in a year and a half.

Our mistakes from 2004 were fresh in our minds and we were hungry to get a few more things right this time.

Under Topp’s leadership, some necessary changes were made to the campaign, notably a clear and respected chain of command within the organization. He also placed a premium on ensuring the leader stayed on script, our platform did not distract from the central message as it did in 2004, and the ground-game resources would be stubbornly allocated to campaigns within close reach of winning.

This last point would come to define our resource-allocation strategy with most ridings benefiting from the advertising, promotion materials and tour events (“big air”), with riding assistance very prudently allotted (“tight ground”). But even with these controllable variables addressed, we still had the enormous task of tackling the issue of strategic voting.

If there was one question that I faced most often as director of communications for the 2004 and 2006 election campaigns, it was this: How are you going to stop so-called strategic voting? It was frustrating, complicated and kept us up at night. We were determined to find a way to beat it.

We needed to attack the Liberals hard to make it unpalatable for our supporters to switch to the Liberals in the final days, as they did in 2004.

The sponsorship scandal was helpful. This question of ethical governance provided Jack and the NDP with an opportunity to fight back against strategic voting — by going on the offence against the Liberals with a greater emphasis than ever before.

But we couldn’t go too far. Here, Topp and other campaign veterans recalled the lesson from Ed Broadbent in 1988, namely never predict the demise of the Liberals. In attempting to strike the right balance, Topp suggested a successful message used by Liberal leader Ross Thatcher to PC voters in the 1964 Saskatchewan election to defeat CCF Premier Woodrow Lloyd: “Lend us your vote.”

The offer was not marriage, but a date. If you weren’t satisfied, you could go back to the Liberals in the next election campaign.

Despite the snickers from some in the Parliamentary Press Gallery, the message struck the right chord with Liberal voters and penetrated in enough places. We were beginning to reverse the effect of strategic voting, and it got thousands of former Liberal voters into the habit of voting New Democrat.

In the 2006 election, the NDP picked up an additional 400,000 votes for a total of 2.5 million. And while the percentage of the popular vote only increased from 16 to 17.5 percent, we won 29 seats, up from 19. Due to the “tight ground” strategy, we won the seats that we had lost by less than 1,000 votes in 2004. We finished in second place in 53 seats.

In many respects, the 2006 campaign was our mulligan, our do-over.

Given the state of the Liberal Party following its loss in 2006, Jack took advantage of the wide berth to attack and oppose the Harper minority government without the threat of sending the country back to the polls.

Meanwhile, the campaign team, under the leadership of Topp and Milling, maintained its activities, as I joined Jack on the Hill to serve as his communications director and oversee the communications efforts of the leader and the caucus.

That’s when we set our sights on Quebec.

One of Jack’s major commitments during the 2003 leadership campaign was to invest in Quebec as part of our rebuilding efforts. This plan was not without controversy with some members, who saw the party lose its footholds in the 1990s in many of our areas of traditional strength, namely BC, Saskatchewan and Ontario.

Many activists argued we needed to focus our limited resources in these areas rather than in a province where we barely registered. But Jack and others, including myself, argued that organizing in Quebec was an integral part of rebuilding in the heartlands.

Party faithful and the next tier of NDP supporters would look to us once they saw we were growing into a national party with a strong Quebec presence. And unlike other places in Canada, Quebec had a voting culture where it could collectively decide to move in one direction — and make big change happen.

Party faithful and the next tier of NDP supporters would look to us once they saw we were growing into a national party with a strong Quebec presence. And unlike other places in Canada, Quebec had a voting culture where it could collectively decide to move in one direction — and make big change happen.

The task before us was monumental.

In the 2000 election, we received 1.8 percent of the Quebec vote. In 2004, the party received 4.6 percent and 7.5 percent in 2006. We saw steady growth with some higher profile candidates running in these later campaigns, but we were far from breaking through.

During this time, our focus group testing suggested that while Bloc and Liberal voters in Quebec had reason to like our party and our leader, they weren’t ready to give the New Democrats a chance. When asked to describe the NDP, one woman said the party resembled an ant — always working hard, plugging away doing good work, but small and easily stepped on.

Quebec voters told us they would consider voting for us only if we met two conditions: shed your reputation as Les centralisateurs and prove we could attract high-calibre candidates who could win.

We took major steps in addressing these two challenges in September 2006, when we made a strategic choice to hold our party’s policy convention in Quebec City. The party adopted an official policy of asymmetrical federalism and other Quebec-friendly policies contained in the Sherbrooke Declaration. Jack also successfully courted former Quebec Liberal cabinet minister Tom Mulcair to deliver a rousing keynote speech.

During this building period in Quebec, critics said that we would never win in the province, and certainly not in a riding like Outremont, where on September 17, 2007, Tom captured the riding in a byelection with 48 percent of the vote. Jack showed Quebecers the NDP could attract credible candidates — and win.

The project seemed to be on sure footing and progress was being made modernizing the Party’s operations. But we hadn’t cracked in the polls and we still had only 30 seats. We had a long way to go.

As we prepared for the coming election, the next decisions about how best to keep the forward momentum would be difficult. After Jack’s five years as leader and two campaigns under his belt, we decided it was time for him to be a little less timid and more audacious.

Jack was used to governing during his long tenure at Toronto’s City Hall. Brian Topp came from the Premier’s Office in Saskatchewan, and I got my start in electoral politics in the BC government, serving as adviser to the premier, the minister of advanced education and the minister of finance. The idea that we were in this to govern was natural to us.

But there were very few issues that were as hotly debated by members of the party and caucus. They’d say: “Don’t say you’re running for prime minister, it’s not credible.” Jack would respond: “I’m not in this just to raise good points, I’m in this to win.”

We understood the risk in saying something that could be dismissed outright: Jack making a pitch to be prime minister as leader of the fourth party with polls showing support in the teens? But if people were ever going to see Jack as a potential prime minister, we had better get around to pitching that idea as part of a leader-centred tour and Jack-focused messaging.

On the first day of the 2008 campaign, Jack stood on the Quebec banks of the Ottawa River with Parliament Hill as the backdrop and kicked it off with the statement “Today, the Prime Minister has quit his job. And I intend to apply for it.”

Jack then got on his campaign plane and went straight to Stephen Harper’s riding, marking the beginning of a campaign in which the NDP, for the first time ever, would spend the legal maximum and match the Conservatives and Liberals dollar-for-dollar.

By 2008, the party’s fundraising capacities had improved dramatically under the leadership of the party’s director of development, Drew Anderson. And while we were still far behind the Conservatives, we were more than competitive with the Liberal Party’s fundraising.

Like the internal debate over Jack’s explicit pitch to become prime minister, the campaign team laboured over the decision to spend $18 million on the campaign.

The stakes were high and we took the future financial viability of the party very seriously. If we borrowed significantly and failed to do well in the campaign, we risked putting the financial future of the party in peril.

But I thought, “If not now, then when?” We had 30 seats, including in Quebec. We also had a popular leader and a united party that was ready for the next campaign. We were also up against a very vulnerable Liberal leader and the economy was headed for a downturn, with people increasingly worried about issues on which we had credibility. We decided to go for it.

We also had to identify whom we were actually running against. This was always a challenge for New Democrats.

In the West, we compete against Conservatives and battle Liberals in Ontario and Atlantic Canada. And with a foothold in Quebec with Mulcair, we identified a few Bloc Québécois and Liberal seats to target.

We came under sharp criticism in 2004 and 2006 for going after the Liberals harder than Stephen Harper. We did so for strategic reasons. We needed to differentiate ourselves from Martin’s Liberals and push back against strategic voting.

I thought, “If not now, then when?” We had 30 seats, including in Quebec. We also had a popular leader and a united party that was ready for the next campaign. We were also up against a very vulnerable Liberal leader and the economy was headed for a downturn, with people increasingly worried about issues on which we had credibility. We decided to go for it.

By 2008, we were in a much different place. Liberal Leader Stéphane Dion had been badly hurt by his lacklustre performance, his organizational incompetence and the successful charge by the Conservatives that he was “not a leader.” If we were running to replace Harper as prime minister, then he should be our focus. After all, it’s his job we want.

We decided to ignore the Liberal Leader as much as possible. But we would also take opportunities to distinguish Layton from the other non-Harper leaders. We used “Strong Leader” as our branding statement to describe Layton in direct contrast to Dion.

We also narrowed the scope of our platform to go along with our tighter campaign message. The way we allocated our resources was equally focused. We invested to ensure the reelection of our incumbents, but we were also funding a targeted growth plan with a very specific list of beachhead seats with ground-game resources and leader’s tour visits.

This included ridings like St. John’s East, Edmonton Strathcona and Welland. In Quebec, it meant five trips to Montreal and other visits to places like Gatineau, where we had hopes for a handful of ridings with strong candidates like Françoise Boivin in Gatineau and Anne Lagacé Dowson in Westmount-Ville Marie in Montreal. Those wins would then be used as toeholds to expand in forthcoming campaigns.

In the end, we picked up 7 seats for a total of 37. But our percentage of the popular vote increased by only 0.7 percent and we actually drew 75,000 fewer votes than our 2006 campaign.

We were very disappointed with the results. We ran a technically excellent campaign and spent $18 million, but still garnered only 18.2 percent of the vote, won 37 seats and placed fourth.

The incremental path that we were on had served us well. But it would no longer be good enough to invest millions of dollars to secure another 10 or so seats. Our running game had got us up the field, but if we were to get into the end zone it was time we started throwing the ball. Although we weren’t where we wanted to be, we had made important gains after three elections under Jack’s leadership.

We had reassembled our traditional vote that we had lost throughout the 1990s and could now count on 18 percent as our “base.” We had the second largest caucus in our party’s history with beachheads in all regions, notably Alberta and Quebec, and in rural, urban and ethnic communities. Our vote and caucus were now national.

We had also built up Jack’s profile and popularity, and transformed the party brand and identity to one that was leader-focused.

Internally, the party had the means to match the Conservatives and Liberals on financing and in other tactical areas. We also had a core campaign team that had now worked together in three election campaigns in just five years.

In the election postmortem, the campaign team assessed virtually every aspect of what needed to be done if we were to end the incremental gains and make the breakthrough. We saw the path through Quebec, understanding a turn in the province would be noticed beyond its borders, especially among progressive voters in Ontario and BC.

To get there, we needed a better message, connecting with a bigger audience, and delivered by a stronger campaign machine.

We started with the machinery of the party, to which I had returned following the 2008 campaign to serve as national director and campaign director. The frequency of federal campaigns under successive minority Parliaments created the opportunity for swift and deep changes to the federal party’s organizational capacity, and we took it.

We overhauled the party’s organization department under the leadership of Nathan Rotman, dismantling an archaic structure that tied federal organizing to the structures — and priorities — of the provincial parties. This allowed us to hire organizers in the regions dedicated exclusively to the federal effort. The new structure also gave us unlimited and unfettered access to the membership, allowing for more aggressive fundraising.

We also fixed the glaring inadequacies with our candidate selection and vetting process. At the very first opportunity after the 2008 campaign, Jack took direct action to ensure that all applicants who sought to become nominees were first screened and then approved by party headquarters. In the end, more than two dozen applicants were rejected.

In the fall of 2010, we turned to messaging. That work began with an aggressive research strategy to identify the next tier of New Democrat voter. For the first time ever, the overwhelming majority of our research dollars went to speaking to people who had never voted New Democrat in their life.

We put a clear question to Viewpoints Research, our polling firm: If we have 18 percent of the vote now, whoaretheonestogetusto25to30 percent? We wanted to find out as much as possible about them. What things did they share in common with our re-assembled base? What things were different?

We found that our next tier of voter was slightly older and slightly better off financially than our base; lived in medium-sized cities; were as likely to be male as female; and were members of the sandwich generation concerned about their children’s future and their aging parents.

This next tier of NDP voter shared three key things in common with our base: they had a deep mistrust of Harper; they did not like Michael Ignatieff, even though they were primarily Liberals; and they liked Jack.

More than anything, these folks were looking for someone in Ottawa they could trust. With Jack scoring well personally, the common denominators of leadership and trust fit in well with our leader-focused branding of the party.

They also saw Parliament, mired in partisan sniping, as a distant and dysfunctional entity that wasn’t getting things done for them, even as health care was suffering, there was a jobs and pension crisis, and life was becoming less and less affordable.

The next election was an opportunity to seize on this sentiment. At the heart of what was wrong with Ottawa were the very players who were responsible for the deterioration. In other words, the status quo was responsible for the dysfunction.

This positioning allowed us to answer the question of who we were running against in the campaign. If we could successfully make the case that the Conservatives, the Liberals and the Bloc were the reason Ottawa was broken, we could paint them as the problem and us as the solution.

And with Jack’s track record of reaching across the aisle to get results — the 2005 “NDP Budget,” the 2008 coalition negotiations with the Liberals and the 2009 agreement with the Conservatives to extend Employment Insurance — there was no one else as credible on the issue of trying to make Ottawa work.

But there were, of course, limits to this approach. Unlike other leaders, Jack was not a push-over, and it took at least two parties to make Parliament work. When it came to the 2011 budget, in the months leading up to it, we laid out realistic “asks” that we promoted extensively to ensure the Conservatives, the media and the public knew where our bottom line was.

At the same time, we made it clear that we were organizationally ready for an election. That way, our decision as to whether to support or oppose the budget was based not on fear of going into an election, but on the merits of the budget. And because we had clearly defined asks, our decision would be easily justifiable to the voters: if the NDP asks were in the budget, we would support, but if they were not, we would oppose. This would seem reasonable.

Although we were ready to go, Jack’s health also played a role in the decision. After battling prostate cancer and recovering from hip surgery with the help of crutches, Jack had two additional people to whom he was going to listen: his doctors and Olivia. Both gave him the green light to run an election campaign if necessary. And after seeing a budget that didn’t come close to meeting the NDP’s asks, Jack and the caucus took the first opportunity to vote nonconfidence (a contempt-of-Parliament motion) in the Harper government.

The fact that the budget did not meet the needs we set out also played into our campaign message. We boiled it down to a tight message that would serve as our ballot question, short enough to fit into a 140 character tweet (or less): Ottawa’s broken. Fix it. This allowed us to channel frustration and anger at Ottawa for whatever was on people’s mind. We could sympathize with their plight, point to a broken Ottawa and encourage them to use their vote for the NDP as a step to fix it.

This also informed the way we crafted our platform into micro-targeted and easy-to-understand policies. The Conservatives were the masters of the simple, achievable promise, so we wanted to contrast, for example, their job creation plan (unconditional corporate tax cuts for big business) with our own better plan (directed tax relief or a small-business tax cut).

This approach to the platform inoculated us against the tag of being the party of multibillion-dollar initiatives. These achievable, fiscally prudent promises, meaningful in the daily lives of people, would also make for better policy announcements on the campaign trail.

First, though, we had to make sure the media were going to come on our tour, a significant portion of which was fully scripted by the time the writ was dropped.

After receiving signals from financially strapped networks and news outlets that the NDP campaign would be the first casualty in election coverage, we dropped the price to join the leader’s tour.

We also went on a full charm offensive. Campaign spokesperson Kathleen Monk and I walked the news bureaus through our whole strategy and explained why they needed to be on our tour: an NDP breakthrough would transform Canadian electoral politics. While very few reporters believed our campaign game plan, our efforts were partially successful: most outlets committed to the first and last weeks. It was a start.

The first week of the campaign didn’t go well, despite a carefully planned tour with a thematic as well a geographical flow with a mixture of policy announcements and rallies. The events of the day, scripted for television with adequate filing time, were to centre on “the shot of the day,” which usually involved Jack interacting with people.

In our first days, the crowds were small and the energy level was low. The media were very skeptical of Jack’s ability to run a full campaign and were looking to report any evidence to validate their assertion. Any inadequacies of our tour defined our coverage.

During the first three campaigns, Jack was an energetic and nimble campaigner. At the beginning of his fourth campaign in 2011, he was still on crutches following recent hip surgery and he couldn’t keep the hours of the previous campaigns. We wanted to take it slow. The entire campaign, after all, was constructed around him, so we couldn’t risk any injury.

It was a rough week. In the Nanos daily tracking poll at the start of the second week, we were down to 13 percent, while Ignatieff and the Liberals were gaining momentum. It felt as though his “red door vs. blue door” pitch in the opening days of the campaign might consolidate the non-Conservative vote.

Both the leader and the senior campaign team had been here before and there was no reason to get distracted. In the campaign headquarters, we had a strictly enforced “no drama” rule.

We began injecting more creativity and money into the event planning while Jack’s health became more surefooted. He dropped the crutches for the cane, and his mobility and energy levels improved.

On the eve of debate week, scheduled during the third week of the campaign, we released our platform. In past campaigns, NDP platforms never really helped the campaign, but they’ve certainly hurt. We weren’t going to let that happen again. We called it “practical first steps” and highlighted prudent steps to be taken in key areas in the first 100 days of taking office.

Our platform strategy worked. The media coverage was either straight up or outright positive. With the first debate only two days away, the timing served us well. Just before the debates, our downward spiral had reversed and for the first time in the campaign, Jack surpassed Ignatieff in the Nanos Leadership Index.

This was a positive development. But we also knew that if we were going to make a breakthrough on May 2, the leaders’ debates needed to be a gamechanger.

Brian Topp was tasked with leading debate preparation. Past debate preps with Jack were exercises in elaborate memorization and complicated policy explanations. But recognizing that this didn’t work, Topp ditched this format for a more simple approach where Jack and the campaign team talked out the overall goals and objectives for the debates, then got them wired into Jack’s DNA.

We also studied the debate format carefully and recognized that we needed to land our punches in the first 60 minutes, anticipating many Canadians would tune in only for the first part and recognizing reporters would begin crafting their stories by then.

We practised the delivery of carefully crafted clips. Think, “You’ve become everything you used to fight against” (to Harper) and “You know, most Canadians, if they don’t show up for work, they don’t get a promotion” (to Ignatieff).

Jack received very favourable reviews in the English-language debate. Two days later was the French language debate, and our one chance to make our pitch to all of Quebec.

For many months leading up to the 2011 election, we knew the New Democrats were the second choice among most Bloc voters and that Jack was seen as the best leader and best prime ministerial candidate among Quebecers.

Our research also told us that Bloc voters would not respond well if we attacked either the Bloc or their leader, Gilles Duceppe. They were generally happy with how the Bloc was performing, but Quebecers also knew something had to change, so we focused on how the status quo in Ottawa, and by extension the Bloc, was not capable of delivering the goals and aspirations of Quebecers.

The hamster spinning in his wheel and the barking dogs became icons of our campaign in Quebec. The message in these ads worked well with both nationalists, who had some contempt for Ottawa, and federalists, who wanted more out of Ottawa. We also invested heavily in our ad buy, spending over $3 million in Quebec alone, triple the amount we spent in 2008.

The extent to which our Quebec message was resonating became plainly obvious at our Montreal rally, held in the Olympia Theatre in the heart of Gilles Duceppe’s riding on Easter Saturday, April 23. The energy at the event was electrifying, and the pictures from the event showed what the polls said: the NDP had risen into first place in Quebec ahead of the Bloc Québécois.

We needed to solidify this post-Easter weekend momentum with a strong end-game advertising blitz to reinforce the campaign’s positive and motivating message, and blunt any possibility of reverse momentum or strategic voting.

The French ad during the last two weeks of the campaign profiled a frustrated Bloc voter who was voting for change with the NDP. The ad featured the tag line “Travaillons ensemble” and featured both Jack and Tom.

The English ad featured only Layton and started with the line “People will try and tell you that you have no choice but to vote for more of the same. But you do have a choice” (eviscerating the red door/blue door Liberal frame). After listing Jack’s easy-to-remember family-friendly priorities, the closing lines packed an emotional punch intended to solidify and motivate our vote:

Together we can do this (we were careful not to define what the “this” was, to let the audience project).

You know where I stand (a reference to Ignatieff).

You know I am a fighter (fighting prostate cancer and recovering from hip surgery).

And I won’t stop until the job is done (Unlike Ignatieff, Jack was in it for the long haul).

On Monday, April 25, one week before election day, we passed the Liberals in the Nanos tracking poll, as non-Conservative support broke in our favour. Two days before election day, the NDP tied the Conservatives for first place in the Nanos overnights.

On election night, we won 103 seats and came in second in another 121 ridings. We got our deposit back in all but 2 ridings, by far the highest percentage of all parties.

A few days after Tom Mulcair was elected leader, I had a meeting with him in Centre Block. Ten years earlier, I had been sitting around Jack and Olivia’s dining room table, helping to map out the project. A decade later, here we were, sitting in the Office of the Leader of the Official Opposition, just one floor up from the Prime Minister’s Office.

Of all the great things we had been able to change within the party, we chatted about the most important accomplishment. For those in the party who didn’t think we could win or didn’t want to win, we created a culture of winning. We no longer debate whether we — or our ideas — are worthy.

Despite the cynicism and pessimism that chokes the culture in Ottawa, Jack was able to defy and confound the critics and connect with people and convince them that working together was worth it to build a better Canada. He changed the political culture, not only for our party, but also for our country.

You can see it the news coverage today: nobody doubts that Tom is taking on Harper to become Canada’s first New Democrat prime minister. And while Jack’s journey was cut far too short, his legacy to us is the belief that the project was not only worthwhile, but also achievable. Now it’s up to us to complete it.

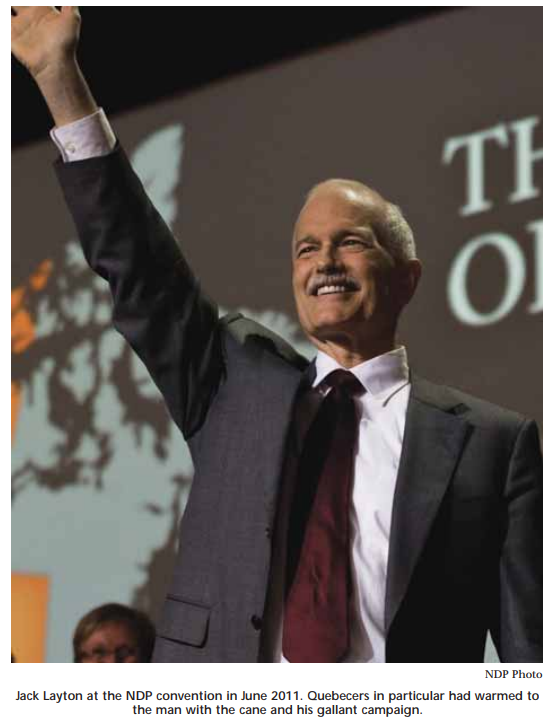

Photo: Shutterstock