Free trade agreements (FTAs) offer better tariff treatment for goods produced in participating countries. That sounds simple in theory, but in practice it’s a complex exercise for companies and customs authorities to figure out where a manufactured good with many different components (such as a new car) originated. Parts might be made in Mexico, the United States and Canada, and assembled in any of the three nations.

Rules of origin define how much of a good’s production must occur in an FTA area in order to benefit from tariff preferences. The negotiating positions that nations take on these rules are influenced by existing supply chain relationships, as well as by intense political lobbying by the companies and workers most directly affected by these rules. And the negotiated outcomes can influence where firms choose to locate and where they get component parts for years.

Compliance with rules of origin can be cumbersome and costly for producers. They must understand the rules and fill out the required paperwork to claim the tariff preferences. Beyond administrative hassles, they may have to switch to suppliers within the FTA area in order to comply with the rules, and this can impose real economic costs if it requires abandoning cheaper or better suppliers located outside the trading bloc.

In his chapter for the IRPP trade volume, former Canadian trade negotiator Sandy Moroz illustrates the policy challenges involved in negotiating these rules. These have become even more acute due to two factors: the fragmentation of production into international supply chains, and the dramatic rise in the number of FTAs around the world from about 40 in the early 1990s to 267, at last count.

Moroz highlights an important but rarely discussed issue in current debates; that is, in large multi-country agreements like the TPP, negotiators can weave together a disjointed web of existing rules under separate FTAs into a common set of rules for a larger combined free trade zone.

Canada and the TPP

Canada alone has 11 active FTAs, with 11 more under negotiation or recently concluded but not implemented. The 12 countries in the TPP region have 32 FTAs that include at least two TPP signatories, and each deal has its own set of rules. The TPP negotiators have effectively woven together 32 different sets of rules into one common rulebook. If implemented, the TPP could significantly reduce compliance costs for producers selling in the larger combined partnership markets, in two ways. First, producers would only have to deal with one set of paperwork, and second, they would be able to get duty-free components or materials from any TPP country, which would enable them to buy from the lowest cost or highest quality suppliers within the zone.

Canada currently has different rules of origin for its 4 FTA partners in the Pacific region, but the TPP could allow it to use just one set of rules when exporting to any of 11 TPP partners.

Canadian producers would be able to get component parts from any of the TPP countries in order to export products duty-free to the larger TPP market. And the TPP offers them opportunities not only to sell final goods, but also to supply parts or materials originating in TPP countries to producers in other TPP countries (including to US producers, which could in turn export duty-free to other TPP members).

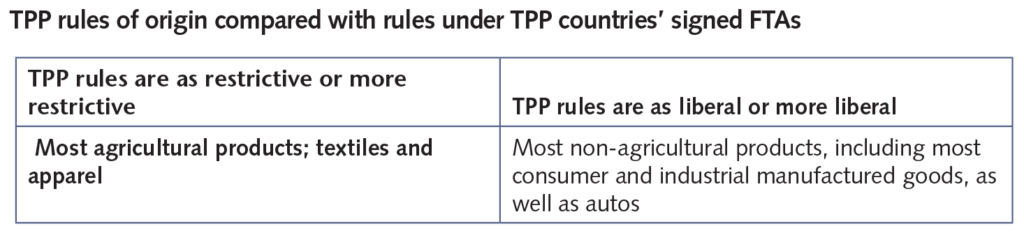

Ultimately, the real gains from the TPP’s proposed single set of rules will depend on how restrictive or liberal they are compared with the rules under the FTAs that currently exist between the TPP countries. Here, Moroz’s chapter breaks new ground with its detailed analysis of the rules in the various trade deals.

Restrictive rules require more components to be made in the area covered by the agreement, whereas rules that are more liberal allow more inputs to be sourced from outside the area.

On the one hand, for many agricultural products, says Moroz, TPP negotiators essentially accommodated parties’ sensitivities by using the most restrictive rule of origin found in any of the existing FTAs involving TPP signatories. In textiles and apparels, the United States was able to largely maintain its highly restrictive rule on the origin of the clothing materials (the so-called “yarn-forward rule,” though some exceptions were granted to Vietnam, a large apparel exporter to the US that sources from non-TPP countries and hopes to sell more to the US market.)

On the other hand, the TPP rules of origin for most non-agricultural products allow TPP producers to import more inputs from outside the TPP area than were allowed under their fragmented web of FTAs involving the TPP signatories.

On autos — a sector of considerable importance in Canada — the controversial negotiations pitted North American and Asian supply chains against each other. The final TPP rules are more liberal than the NAFTA rules, and they effectively allow Japanese car producers to maintain their existing Asian-based supply chains.

This outcome has revealed a split within the North American auto industry. Vehicle assemblers and larger (tier-1) parts suppliers generally support the TPP. These firms have the size and resources to adapt to the agreement’s competitive challenges and market opportunities.

Conversely, smaller (tier-2) parts producers in North America are concerned about the TPP. These regionally based and regionally dependent companies generally make smaller or less complex components for the tier-1 parts producers and vehicle assemblers. They worry the TPP will expose them to stiff Asian competition (which includes lower-wage producers in non-TPP countries such as China and Thailand, which make components that would be allowed to be sourced from outside the TPP bloc).

Moroz argues that while North America’s imports of vehicles and parts from Japan and other Asian countries may rise over time under the TPP, the majority of the vehicles sold in North America likely would continue to be produced in North America. This acts as a gravitational pull for nearby parts suppliers.

But the key question for Canada’s auto sector is, where in North America will vehicles be assembled in the future? As assembly investment shifted to the southern US states — attracted in part by lower wages and state government incentives — and, more recently, to Mexico, with its lower cost structure, Canada’s share of North American light vehicle production fell from around 18 percent in 1999 to 13 percent in 2014.

The vehicle mandates for several Canadian-based assembly plants are up for renewal in the next few years. Canada’s ability to retain vehicle production and attract new investment will depend, first, on general competitive factors such as productivity and labour costs, infrastructure, taxes, regulations and the medium-term outlook for the Canadian dollar; and second, on Canada’s response to incentives offered by governments elsewhere in the region. These factors likely will be much more important for future vehicle assembly and parts production in Canada (and the northern US states) than the removal of tariffs on Japanese-made vehicles and less restrictive TPP rules of origin.

Moroz argues that if Canada were to stay outside of the TPP, NAFTA’s more restrictive rules of origin wouldn’t shield its auto producers from increased competition in their main market, the United States. If Canada were to join the TPP, however, its auto producers would not only have the chance to remain an integral part of the North American supply chain already established under NAFTA — both as suppliers and buyers — they would also have access to the same new opportunities as producers in other TPP countries to maintain their competitive positions in North America and other partnership markets.

Looking beyond the TPP

Rules of origin are a key feature of FTAs, but they can impose economic costs and distort trade. In theory, the best way to deal with the current web of overlapping rules of origin would be to remove the need for them by eliminating tariffs multilaterally, though this is unlikely to occur in the current political context. A useful interim step for the World Trade Organization would therefore be to develop a set of harmonized preferential rules of origin, with the goal of making them mandatory and liberal. Achieving agreement on these would not be easy, but the possibility should nevertheless be pursued.

In the meantime, individual countries should try to weave together their existing FTAs, something that wouldn’t necessarily require harmonizing rules across agreements, which would be tricky. Indeed, Canada included provisions to this effect in FTAs it has signed since NAFTA, but to date they have not been activated.

Ultimately, dependence on the United States remains the dominant factor in Canada’s approach to rules of origin negotiations. Canada needs to continue to seek rules that reflect the importance of the US, both as a major supplier of components and materials and as a major market for exports in many Canadian sectors. Moroz says that Canada should continue to be as creative and flexible as it has been in FTA negotiations since it negotiated NAFTA over 20 years ago, adapting its approach to different circumstances and using its full arsenal of tools to achieve outcomes that meet its needs.

Photo: Lightspring / Shutterstock.com

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.